16th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP ‘97),

October 5–8, 1997, Saint-Malo, France

Hermann Härtig

Michael Hohmuth

Jochen Liedtke

Sebastian Schönberg

Jean Wolter

Dresden University of Technology

Department of Computer Science

D-01062 Dresden, Germany

email: l4-linux@os.inf.tu-dresden.de

IBM T. J. Watson Research Center

30 Saw Mill River Road

Hawthorne, NY 10532, USA

email: jochen@watson.ibm.com

This research was supported in part by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through the Sonderforschungsbereich 358. Copyright c 1997 by the Association for Computing Machinery, Inc. Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, to republish, post on servers, or redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from Publications Dept, ACM Inc., fax +1 (212) 869-0481, or permissions@acm.org.

这项研究得到了德国研究基金会(DFG)通过 Sonderforschungsbereich 358 的部分支持。Copyright 1997 by the Association for Computing Machinery, Inc. 允许免费制作本作品部分或全部的数字或硬拷贝,供个人或课堂使用,前提是不以盈利或商业利益为目的制作或分发副本,并且拷贝的第一页要注明本通知和完整的引文。由 ACM 以外的其他人拥有的本作品的组成部分的版权必须得到尊重。允许摘录并注明出处。以其他方式复制、再版、在服务器上发布或重新分发到列表,需要事先获得特定许可和/或支付费用。请向 ACM 公司出版部申请许可,传真:+1(212)869-0481,或permissions@acm.org。

摘要 Abstract

First-generation μ-kernels have a reputation for being too slow and lacking sufficient flexibility. To determine whether L4, a lean second-generation μ-kernel, has overcome these limitations, we have repeated several earlier experiments and conducted some novel ones. Moreover, we ported the Linux operating system to run on top of the L4 μ-kernel and compared the resulting system with both Linux running native, and MkLinux, a Linux version that executes on top of a first-generation Mach-derived μ-kernel.

第一代微内核以速度太慢和缺乏足够的灵活性而闻名。为了确定第二代微内核 L4 是否克服了这些限制,我们重复了几个早期的实验,并进行了一些新的实验。此外,我们将 Linux 操作系统移植到 L4 微内核之上运行,并将生成的系统与原生的 Linux 和 MkLinux(在第一代 Mach 衍生的 μ 内核之上执行的 Linux 版本)进行比较。

For L4Linux, the AIM benchmarks report a maximum throughput that is only 5% lower than that of native Linux. The corresponding penalty is 5 times higher for a co-located in-kernel version of MkLinux, and 7 times higher for a user-level version of MkLinux. These numbers demonstrate both that it is possible to implement a high-performance conventional operating system personality above a μ-kernel, and that the performance of the μ-kernel is crucial to achieving this.

对于 L4Linux,AIM 基准测试报告的最大吞吐量仅比原生 Linux 低 5%。对于位于同一位置的内核版本的 MkLinux,相应的惩罚要高出 5 倍,而对于 MkLinux 的用户级版本,则是 7 倍。这些数字表明,在微内核之上实现高性能的传统操作系统是可能的,并且微内核的性能对于实现这一点至关重要。

Further experiments illustrate that the resulting system is highly extensible and that the extensions perform well. Even real-time memory management including second-level cache allocation can be implemented at the user level, coexisting with L4Linux.

进一步的实验表明,所得到的系统是高度可扩展的,并且扩展后的系统表现良好。甚至包括二级缓存分配在内的实时内存管理也可以在用户级实现,与 L4Linux 共存。

1 介绍 Introduction

The operating systems research community has almost completely abandoned research on system architectures that are based on pure μ-kernels, i. e. kernels that provide only address spaces, threads, and IPC, or an equivalent set of primitives. This trend is due primarily to the poor performance exhibited by such systems constructed in the 1980s and early 1990s. This reputation has not changed even with the advent of faster μ-kernels; perhaps because these μ-kernel have for the most part only been evaluated using microbenchmarks.

操作系统研究界几乎完全放弃了对基于纯微内核的系统架构的研究,即只提供地址空间、线程和 IPC 或一组等效原语的内核。这种趋势主要是由于在 20 世纪 80 年代和 90 年代初构建的这类系统表现出的性能不佳。即使出现了更快的微内核,这种声誉也没有改变;也许是因为这些微内核在大多数情况下只使用微基准进行评估。

Many people in the OS research community have adopted the hypothesis that the layer of abstraction provided by pure μ-kernels is either too low or too high. The “too low” faction concentrated on the extensible-kernel idea. Mechanisms were introduced to add functionality to kernels and their address spaces, either pragmatically (co-location in Chorus or Mach) or systematically. Various means were invented to protect kernels from misbehaving extensions, ranging from the use of safe languages [5] to expensive transaction-like schemes [34]. The “too high” faction started building kernels resembling a hardware architecture at their interface [12]. Software abstractions have to be built on top of that. It is claimed that μ-kernels can be fast on a given architecture but cannot be moved to other architectures without losing much of their efficiency [19].

操作系统研究界的许多人都采用了这样的假设:纯微内核所提供的抽象层要么太低,要么太高。“太低"的一派集中在可扩展内核的想法上。引入了一些机制来增加内核及其地址空间的功能,无论是实用性的(Chorus 或 Mach 中的同位)还是系统性的。人们发明了各种方法来保护内核不受不正当扩展的影响,从使用安全语言[5]到昂贵的类似事务的方案[34]。“太高"派开始在他们的接口上构建类似于硬件架构的内核[12]。软件抽象必须建立在这个基础之上。据称,微内核可以在给定的架构上快速运行,但不能在不损失其效率的情况下移动到其他架构[19]。

In contrast, we investigate the pure μ-kernel approach by systematically repeating earlier experiments and conducting some novel experiments using L4, a second-generation μkernel. (Most first-generation μ-kernels like Chorus [32] and Mach [13] evolved from earlier monolithic kernel approaches; second-generation μ-kernels like QNX [16] and L4 more rigorously aim at minimality and are designed from scratch [24].)

相比之下,我们通过系统地重复先前的实验,并使用第二代微内核 L4 进行一些新的实验,来研究纯微内核的方法。(大多数第一代微内核,如 Chorus[32]和 Mach[13],都是从早期的宏内核方法演变而来;第二代微内核,如 QNX[16]和 L4,更严格地以最小化为目标,从头设计[24])。

The goal of this work is to show that μ-kernel-based systems are usable in practice with good performance. L4 is a lean kernel featuring fast message-based synchronous IPC, a simple-to-use external paging mechanism, and a security mechanism based on secure domains. The kernel implements only a minimal set of abstractions upon which operating systems can be built [22]. The following experiments were performed:

这项工作的目标是证明基于微内核的系统在实践中具有良好的性能。L4 是一个精简的内核,具有快速的基于消息的同步 IPC、简单易用的外部分页机制和基于安全域的安全机制。内核只实现了一组最小的抽象,在此基础上可以构建操作系统[22]。进行以下实验:

A monolithic Unix kernel, Linux, was adapted to run as a user-level single server on top of L4. This makes L4 usable in practice and gives us some evidence (at least an upper bound) on the penalty of using a standard OS personality on top of a fast μ-kernel. The performance of the resulting system is compared to the native Linux implementation and MkLinux, a port of Linux to a Mach 3.0 derived μ-kernel [10].

一个 Unix 宏内核,Linux,被改编为在 L4 之上作为用户级的单一服务器运行。这使得 L4 在实践中可用,并为我们提供了一些证据(至少是上限),说明在快速微内核上使用标准操作系统的代价。最终系统的性能与原生 Linux 实现和 MkLinux 进行了比较,MkLinux 是 Linux 对 Mach 3.0 衍生的微内核的一个移植[10]。

Furthermore, comparing L4Linux and MkLinux gives us some insight into how the μ-kernel efficiency influences the overall system performance.

此外,通过比较 L4Linux 和 MKLinux,我们可以深入了解微内核效率如何影响整个系统的性能。

The objective of three further experiments was to show the extensibility of the system and to evaluate the achievable performance. Firstly, pipe-based local communication was implemented directly on the μkernel and compared to the native Linux implementation. Secondly, some mapping-related OS extensions (also presented in the recent literature on extensible kernels) have been implemented as user-level tasks on L4. Thirdly, the first part of a user-level real-time memory management system was implemented. Coexisting with L4Linux, the system controls second-level cache allocation to improve the worst-case performance of real-time applications.

三个进一步实验的目的是展示系统的可扩展性,并评估可实现的性能。首先,在微内核上直接实现了基于管道的本地通信,并与原生 Linux 实现进行了比较。其次,一些与映射相关的操作系统扩展(在最近关于可扩展内核的文献中也有介绍)已经在 L4 上实现为用户级任务。第三,实现了用户级实时内存管理系统的第一部分。与 L4Linux 共存时,该系统控制二级缓存分配,以提高实时应用程序的最坏情况下的性能。

To check whether the L4 abstractions are reasonably independent of the Pentium platform L4 was originally designed for, the μ-kernel was reimplemented from scratch on an Alpha 21164, preserving the original L4 interface.

为了检查 L4 抽象是否合理地独立于 L4 最初设计的奔腾平台,在 Alpha 21164 上从头重新实现了微内核,保留了原始的 L4 接口。

Starting from the IPC implementation in L4/Alpha, we also implemented a lower-level communication primitive, similar to Exokernel’s protected control transfer [12], to find out whether and to what extent the L4 IPC abstraction can be outperformed by a lower-level primitive.

从 L4/Alpha 中的 IPC 实现开始,我们还实现了一个较低级别的通信原语,类似于 ExoKernel 的受保护控制转移[12],以找出较低级别的原语是否以及在多大程度上可以超越 L4 IPC 抽象。

After a short overview of L4 in Section 3, Section 4 explains the design and implementation of our Linux server. Section 5 then presents and analyzes the system’s performance for pure Linux applications, based on microbenchmarks as well as macro benchmarks. Section 6 shows the extensibility advantages of implementing Linux above a μkernel. In particular, we show

在第 3 节对 L4 进行了简短的概述之后,第 4 节解释了我们的 Linux 服务器的设计和实现。然后,第 5 节介绍并分析了基于微基准测试和宏基准测试的纯 Linux 应用程序的系统性能。第 6 节展示了在 μKernel 上实现 Linux 的可扩展性优势。特别地,我们展示了

how performance can be improved by implementing some Unix services and variants of them directly above the L4 μ-kernel,

如何通过直接在 L4 微内核之上实现一些 UNIX 服务及其变体来提高性能,

how additional services can be provided efficiently to the application, and

如何有效地向应用程序提供附加服务,以及

how whole new classes of applications (e. g. real-time) can be supported concurrently with general-purpose Unix applications.

如何在通用的 Unix 应用中同时支持全新的应用类别(如实时)。

Finally, Section 7 discusses alternative basic concepts from a performance point of view.

最后,第 7 节从性能的角度讨论了其他基本概念。

2 相关工作 Related Work

Most of this paper repeats experiments described by Bershad et al. [5], des Places, Stephen & Reynolds [10], and Engler, Kaashoek & O’Toole [12] to explore the influence of a second-generation μ-kernel on user-level application performance. Kaashoek et al. describe in [18] how to build a Unix-compatible operating system on top of a small kernel. We concentrate on the problem of porting an existing monolithic operating system to a μ-kernel.

本文的大部分内容重复了 Bershad 等人 [5], des Places, Stephen & Reynolds [10], 和 Engler, Kaashoek & O’Toole [12]描述的实验,探讨第二代微内核对用户级应用程序性能的影响。Kaashoek 等人在[18]中描述了如何在小型内核上构建兼容 UNIX 的操作系统。我们集中讨论将现有的宏内核操作系统移植到微内核的问题。

A large bunch of evaluation work exists that addresses how a certain application or system functionality, e. g. a protocol implementation, can be accelerated using system specialization [31], extensible kernels [5, 12, 34], layered path organization [30], etc. Two alternatives to the pure μ-kernel approach, grafting and the Exokernel idea, are discussed in more detail in Section 7.

有大量评估工作解决了如何利用系统专业化[31]、可扩展内核[5,12,34]、分层路径组织[30]等来加速某种应用或系统功能,例如协议实现。第 7 节将更详细地讨论纯微内核方法的两个替代方案,即嫁接和外核思想。

Most of the performance evaluation results published elsewhere deal with parts of the Unix functionality. An analysis of two complete Unix-like OS implementations regarding memory-architecture-based influences is described in [8]. Currently, we do not know of any other full Unix implementation on a second-generation μ-kernel. And we know of no other recent end-to-end performance evaluation of μ-kernel-based OS personalities. We found no substantiation for the “common knowledge” that early Mach 3.0-based Unix single-server implementations achieved a performance penalty of only 10% compared to bare Unix on the same hardware. For newer hardware, [9] reports penalties of about 50%.

在其他地方发布的大多数性能评估结果都涉及部分 UNIX 功能。[8]中描述了关于基于内存体系结构的影响的两个完整的类 Unix 操作系统实现的分析。目前,我们还不知道在第二代微内核上有任何其他完整的 UNIX 实现。据我们所知,目前还没有其他基于微内核的操作系统的端到端性能评估。有传言说早期的基于 Mach 3.0 的 UNIX 单服务器实现与相同硬件上的裸 UNIX 相比,性能损失仅为 10%,我们没有发现这一"常识"的证据。对于较新的硬件,[9]报告的惩罚约为 50%。

3 L4 基本要素 L4 Essentials

The L4 μ-kernel [22] is based on two basic concepts, threads, and address spaces. A thread is an activity executing inside an address space. Cross-address-space communication, also called inter-process communication (IPC), is one of the most fundamental μ-kernel mechanisms. Other forms of communication, such as remote procedure calls (RPC) and controlled thread migration between address spaces, can be constructed from the IPC primitive.

L4 微内核[22]基于两个基本概念:线程和地址空间。线程是在地址空间内执行的活动。跨地址空间通信,也称为进程间通信(IPC),是最基本的微内核机制之一。其他形式的通信,如远程过程调用(RPC)和地址空间之间的受控线程迁移,可以从 IPC 原语构建。

A basic idea of L4 is to support the recursive construction of address spaces by user-level servers outside the kernel. The initial address space σ0 essentially represents the physical memory. Further address spaces can be constructed by granting, mapping, and unmapping flex pages, logical pages of size 2n, ranging from one physical page up to a complete address space. The owner of the address space can grant or map any of its pages to another address space, provided the recipient agrees. Afterward, the page can be accessed in both address spaces. The owner can also unmap any of its pages from all other address spaces that received the page directly or indirectly from the unmapped. The three basic operations are secure since they work on virtual pages, not on physical page frames. So the invoker can only map and unmap pages that have already been mapped into its own address space.

L4 的基本思想是支持内核外部的用户级服务器递归构造地址空间。初始地址空间 σ0 实质上表示物理内存。可以通过授予、映射和取消映射大小为 2n 的逻辑页(范围从一个物理页到完整的地址空间)来构建更多的地址空间。如果接收者同意,地址空间的所有者可以将其任何页面授予或映射到另一个地址空间。之后,该页可以在两个地址空间中被访问。所有者也可以从所有其他直接或间接收到该页的地址空间解除其任何页的映射。这三个基本操作是安全的,因为它们在虚拟页面上工作,而不是在物理页帧上。因此,调用者只能映射和取消映射已经映射到自己的地址空间的页面。

All address spaces are thus constructed and maintained by user-level servers, also called pagers; only the grant, map and unmap operations are implemented inside the kernel. Whenever a page fault occurs, the μ-kernel propagates it via IPC to the pager currently associated with the faulting thread. The threads can dynamically associate individual pagers with themselves. This operation specifies to which user-level pager the μ-kernel should send the page-fault IPC. The semantics of a page fault is completely defined by the interaction of the user thread and pager. Since the bottom-level pagers in the resulting address-space hierarchy are main-memory managers, this scheme enables a variety of memory-management policies to be implemented on top of the μ-kernel.

因此,所有地址空间都由用户级服务器(也称为分页器)构建和维护;在内核中只实现了 grant、map 和 unmap 操作。无论何时发生页面错误,微内核都会通过 IPC 将其传播到当前与错误线程相关联的分页器。线程可以动态地将各个分页器与其自身相关联。此操作指定微内核应将页面错误 IPC 发送到哪个用户级分页器。缺页的语义完全由用户线程和分页器的交互来定义。由于所得到的地址空间层次结构中的底层分页器是主内存管理器,因此该方案能够在微内核之上实现各种内存管理策略。

I/O ports are treated as parts of address spaces so that they can be mapped and unmapped in the same manner as memory pages. Hardware interrupts are handled as IPC. The μkernel transforms an incoming interrupt into a message to the associated thread. This is the basis for implementing all device drivers as user-level servers outside the kernel.

I/O 端口被视为地址空间的一部分,因此它们可以以与内存页相同的方式映射和取消映射。硬件中断作为 IPC 处理。微内核将传入的中断转换为相关线程的消息。这是将所有设备驱动程序实现为内核之外的用户级服务器的基础。

In contrast to interrupts, exceptions, and traps are synchronous to the raising thread. The kernel simply mirrors them to the user level. On the Pentium processor, L4 multiplexes the processor’s exception handling mechanism per thread: an exception pushes the instruction pointer and flags on the thread’s user-level stack and invokes the thread’s (user-level) exception or trap handler.

与中断相反,异常和陷阱与引发线程同步。内核只是将它们镜像到用户层。在奔腾处理器上,L4 为每个线程复用了处理器的异常处理机制:异常将指令指针和标志推送到线程的用户级堆栈上,并调用线程的(用户级)异常或陷阱处理程序。

A Pentium-specific feature of L4 is the small-address space optimization. Whenever the currently-used portion of address space is “small”, 4 MB up to 512 MB, this logical space can be physically shared through all page tables and protected by Pentium’s segment mechanism. As described in [22], this simulates a tagged TLB for context switching to and from small address spaces. Since the virtual address space is limited, the total size of all small spaces is also limited to 512 MB by default. The described mechanism is solely used for optimization and does not change the functionality of the system. As soon as a thread accesses data outside its current small space, the kernel automatically switches it back to the normal 3 GB space model. Within a single task, some threads might use the normal large space while others operate on the corresponding small space.

奔腾特有的 L4 功能是小地址空间优化。只要当前使用的地址空间部分是 “小 “的(4MB 到 512MB),该逻辑空间就可以通过所有页表进行物理共享,并通过奔腾的分段机制进行保护。如[22]中所述,这模拟了用于在小地址空间之间进行上下文切换的标记 TLB。由于虚拟地址空间有限,默认情况下,所有小空间的总大小也限制为 512 MB。所描述的机制仅用于优化,并且不改变系统的功能。只要线程访问其当前小空间之外的数据,内核就会自动将其切换回正常的 3GB 空间模型。在单个任务中,一些线程可能使用正常的大空间,而其他线程则在相应的小空间上操作。

Pentium-Alpha-MIPS

Originally developed for the 486 and Pentium architecture, experimental L4 implementations now exist for Digital’s Alpha 21164 [33] and MIPS R4600 [14]. Both new implementations were designed from scratch. L4/Pentium, L4/Alpha, and L4/MIPS are different μ-kernels with the same logical API. However, the μ-kernel-internal algorithms and the binary API (use of registers, word and address size, encoding of the kernel call) are processor dependent and optimized for each processor. Compilers and libraries hide the binary API differences from the user. The most relevant user-visible difference probably is that the Pentium μ-kernel runs in 32bit mode whereas the other two are 64-bit-mode kernels and therefore support larger address spaces.

最初为 486 和奔腾架构开发,现在为 Digital 公司的 Alpha 21164[33]和 MIPS R4600[14]也有实验性的 L4 实现。这两个新的实现都是从零开始设计的。L4/Pentium、L4/Alpha 和 L4/MIPS 是具有相同逻辑 API 的不同微内核。然而,微内核内部算法和二进制 API(寄存器的使用、字和地址大小、内核调用的编码)是依赖于处理器的,并且针对每个处理器进行了优化。编译器和库对用户隐藏了二进制 API 的差异。最相关的用户可见差异可能是奔腾微内核在 32 位模式下运行,而其他两个是 64 位模式内核,因此支持更大的地址空间。

The L4/Alpha implementation is based on a complete replacement of Digital’s original PALcode [11]. Short, time-critical operations are hand-tuned and completely performed in PALcode. Longer, interruptible operations enter PALcode, switch to kernel mode, and leave PALcode to perform the remainder of the operation using standard machine instructions. A comparison of the IPC performance of the three L4 μ-kernels can be found in [25].

L4/Alpha 的实现是基于对 Digital 的原始 PALcode[11]的完全替换。短的、时间紧迫的操作是手工调整的,完全在 PALcode 中执行。较长的、可中断的操作进入 PALcode,切换到内核模式,然后离开 PALcode,使用标准机器指令执行剩余的操作。三个 L4 微内核的 IPC 性能比较可以在[25]中找到。

4 基于 L4 的 Linux Linux on Top of L4

Many classical systems emulate Unix on top of a μ-kernel. For example, monolithic Unix kernels were ported to Mach [13, 15] and Chorus [4]. Very recently, a single-server experiment was repeated with Linux and newer, optimized versions of Mach [10].

许多经典系统在微内核之上模拟 UNIX。例如,UNIX 宏内核被移植到 Mach[13,15]和 Chorus[4]。最近,在 Linux 和更新的优化版本的 Mach[10]上重复了单服务器实验。

To add a standard OS personality to L4, we decided to port Linux. Linux is stable, performs well, and is on the way to becoming a de-facto standard in the freeware world. Our goal was a 100%-Linux-compatible system that could offer all the features and flexibility of the underlying μ-kernel.

为了让 L4 更为标准,我们决定移植 Linux。Linux 是稳定的,性能良好,并且正在成为自由软件世界中事实上的标准。我们的目标是一个 100%Linux 兼容的系统,它可以提供底层微内核的所有特性和灵活性。

To keep the porting effort low, we decided to forego any structural changes to the Linux kernel. In particular, we felt that it was beyond our means to tune Linux to our μ-kernel in the way the Mach team tuned their single-server Unix to the features of Mach. As a result, the performance measurements shown can be considered a baseline comparison level for the performance that can be achieved with more significant optimizations. A positive implication of this design decision is that new versions of Linux can be easily adapted to our system.

为了减少移植的工作量,我们决定放弃对 Linux 内核的任何结构性更改。特别是,我们觉得将 Linux 调整为微内核超出了我们的能力范围,就像 Mach 团队将他们的单服务器 Unix 调整为 Mach 一样。因此,所示的性能度量可以被视为通过更重要的优化可以实现的性能的基准比较级别。这一设计决策的积极意义在于,新版本的 Linux 可以很容易地适应我们的系统。

4.1 Linux 基本要素 Linux Essentials

Although originally developed for x86 processors, the Linux kernel has been ported to several other architectures, including Alpha, M68k, and SPARC [27]. Recent versions contain a relatively well-defined interface between architecture-dependent and independent parts of the kernel [17]. All interfaces described in this paper correspond to Linux version 2.0.

虽然最初是为 x86 处理器开发的,但 Linux 内核已被移植到其他几种架构中,包括 Alpha、M68K 和 SPARC[27]。最近的版本在内核的依赖于架构的部分和独立部分之间包含了一个相对定义良好的接口[17]。本文中描述的所有接口都对应于 Linux 2.0 版本。

Linux’s architecture-independent part includes process and resource management, file systems, networking subsystems, and all device drivers. Altogether, these are about 98% of the Linux/x86 source distribution of kernel and device drivers. Although the device drivers belong to the architecture-independent part, many of them are of course hardware dependent. Nevertheless, provided the hardware is similar enough, they can be used in different Linux adaptions.

Linux 独立于体系结构的部分包括进程和资源管理、文件系统、网络子系统和所有设备驱动程序。总之,这些占了 Linux/x86 源代码的大约 98%。虽然设备驱动程序属于与体系结构无关的部分,但它们中的许多当然是依赖于硬件的。然而,如果硬件足够相似,它们可以在不同的 Linux 适配中使用。

Except perhaps exchanging the device drivers, porting Linux to a new platform should only entail changes to the architecture-dependent part of the system. This part completely encapsulates the underlying hardware architecture. It provides support for interrupt-service routines, low-level device driver support (e. g., for DMA), and methods for interaction with user processes. It also implements switching between Linux kernel contexts, copyin/copyout for transferring data between kernel and user address spaces, signaling, mapping/unmapping mechanisms for constructing address spaces, and the Linux system-call mechanism. From the user’s perspective, it defines the kernel’s application binary interface.

除了可能交换设备驱动程序之外,将 Linux 移植到新平台应该只需要对系统的依赖于体系结构的部分进行更改。这部分完全封装了底层硬件架构。它提供了对中断服务程序的支持、底层设备驱动程序支持(例如,对 DMA 的支持)以及用于与用户进程交互的方法。它还实现了 Linux 内核上下文之间的切换、用于在内核和用户地址空间之间传输数据的 copyin/copyout、信号、用于构建地址空间的映射/取消映射机制以及 Linux 系统调用机制。从用户的角度来看,它定义了内核的应用程序二进制接口。

For managing address spaces, Linux uses a three-level architecture-independent page table scheme. By defining macros, the architecture-dependent part maps it to the underlying low-level mechanisms such as hardware page tables or software TLB handlers.

为了管理地址空间,Linux 使用了一个与架构无关的三层页表方案。通过定义宏,依赖于架构的部分将其映射到底层的低级机制,如硬件页表或软件 TLB 处理程序。

Interrupt handlers in Linux are subdivided into top halves and bottom halves. Top halves run at the highest priority, are directly triggered by hardware interrupts, and can interrupt each other. Bottom halves run at the next lower priority. A bottom-half handler can be interrupted by top halves but not by other bottom halves or the Linux kernel.

Linux 中的中断处理程序被细分为上半区和下半区。上半部分以最高的优先级运行,直接由硬件中断触发,并且可以相互中断。下半部分则以次低的优先级运行。一个底层处理程序可以被顶层处理程序中断,但不能被其他底层处理程序或 Linux 内核中断。

4.2 L4Linux - 设计和实现 Design and Implementation

We chose to be fully binary compliant with Linux/x86. Our compatibility test was that any off-the-shelf software for Linux should run on L4Linux. Therefore, we used all application-binary-interface definition header files unmodified from the native Linux/x86 version.

我们选择与 Linux/x86 完全二进制兼容。我们的兼容性测试是,任何现成的 Linux 软件都应能在 L4Linux 上运行。因此,我们使用所有原生 Linux/x86 版本的应用程序二进制接口定义头文件。

In keeping with our decision to minimize L4-specific changes to Linux, we restricted all our modifications to the architecture-dependent part. Also, we restricted ourselves from making any Linux-specific modifications to the L4 μkernel. Porting Linux was therefore also an experiment checking whether performance can be achieved without significant μ-kernel-directed optimizations in the Linux kernel and whether the L4 interface is truly general and flexible.

为了与我们的决定保持一致,即尽量减少对 Linux 的 L4 特定的修改,我们将所有的修改限制在与架构相关的部分。同时,我们也限制自己不对 L4 的微内核做任何针对 Linux 的修改。因此,移植 Linux 也是一个实验,检查是否可以在不对 Linux 内核进行重大的微内核定向优化的情况下实现高性能,以及 L4 接口是否真正通用和灵活。

Linux 服务器(“Linux 内核”) The Linux Server (“Linux Kernel”)

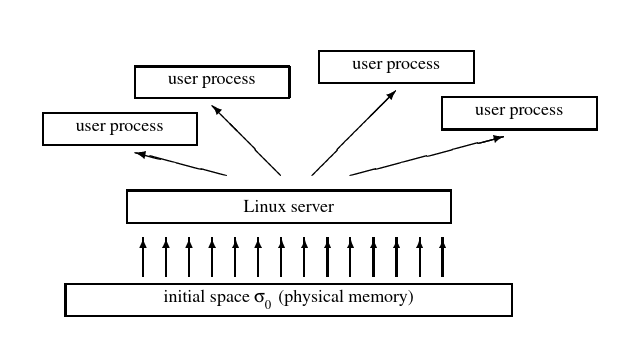

Figure 1: L4Linux Address Spaces. Arrows denote mapping. The Linux server space can be a subset of σ0. Although plotted as smaller boxes, the user address spaces can be larger than the server’s address space.

图1:L4Linux地址空间。箭头表示映射。Linux服务器空间可以是σ0的一个子集。虽然图中的方框较小,但用户的地址空间可以比服务器的地址空间大。

Native Linux maps physical memory one-to-one to the kernel’s address space. We used the same scheme for the L4Linux server. Upon booting, the Linux server requests memory from its underlying pager. Usually, this is σ0 , which maps the physical memory that is available for the Linux personality one-to one into the Linux server’s address space (see Figure 1). The server then acts as a pager for the user processes it creates.

原生 Linux 将物理内存一对一地映射到内核的地址空间。我们对 L4Linux 服务器使用了同样的方案。在启动时,Linux 服务器向其底层寻呼机请求内存。通常,这就是 σ0,它将 Linux 可用的物理内存一对一地映射到 Linux 服务器的地址空间(见图 1)。然后,服务器作为其创建的用户进程的分页器。

For security reasons, the true hardware page tables are kept inside L4 and cannot be directly accessed by user-level processes. As a consequence, the Linux server has to keep and maintain additional logical page tables in its own address space. For the sake of simplicity, we use the original Pentium-adapted page tables in the server unmodified as logical page tables. Compared to native Linux, this doubles the memory consumption by page tables. Although current memory pricing lets us ignore the additional memory costs, double bookkeeping could decrease speed. However, the benchmarks in Section 5 suggest that this is not a problem.

出于安全考虑,真正的硬件页表被保存在 L4 内,不能被用户级进程直接访问。因此,Linux 服务器必须在自己的地址空间中保留和维护额外的逻辑页表。为了简单起见,我们在服务器中使用未经修改的原始奔腾适配页表作为逻辑页表。与原生 Linux 相比,这使页表的内存消耗增加了一倍。尽管目前的内存价格让我们忽略了额外的内存成本,但内存冗余可能会降低速度。然而,第 5 节中的基准测试表明,这不是一个问题。

Only a single L4 thread is used in the L4Linux server for handling all activities induced by system calls and page faults. Linux multiplexes this thread to avoid blocking in the kernel. Multithreading at the L4 level might have been more elegant and faster. However, it would have implied a substantial change to the original Linux kernel and was thus rejected.

在 L4Linux 服务器中,仅使用单个 L4 线程来处理由系统调用和页面错误引起的所有活动。Linux 多路复用此线程以避免在内核中阻塞。L4 级别的多线程处理可能会更优雅、更快。然而,这意味着对原始 Linux 内核进行了实质性的更改,因此被拒绝了。

The native uniprocessor Linux kernel uses interrupt disabling for synchronization and critical sections. Since L4 also permits privileged user-level tasks, e. g. drivers, to disable interrupts, we could use the existing implementation without modification.

原生的单处理器 Linux 内核在同步和关键部分使用禁用中断。由于 L4 也允许有特权用户级任务,如驱动程序,要禁用中断,我们可以使用现有的实现,而无需修改。

中断处理和设备驱动程序 Interrupt Handling and Device Drivers

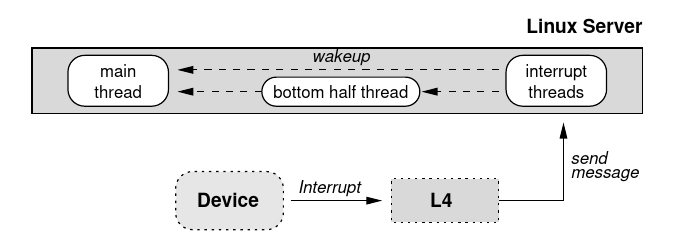

The L4 μ-kernel maps hardware interrupts to messages (Figure 2). The Linux top-half interrupt handlers are implemented as threads waiting for such messages, one thread per interrupt source:

L4 微内核将硬件中断映射为消息(图 2)。Linux 上半部分的中断处理程序被实现为等待这种消息的线程,每个中断源有一个线程:

interrupt handler thread:

do

wait for interrupt {L4-IPC};

top half interrupt handler()

od.

Another thread executes all bottom halves once the pending top halves have been completed. Executing the interrupt threads and the bottom-half thread on a priority level above that of the Linux server thread avoids concurrent execution of interrupt handlers and the Linux server, exactly as on native uniprocessor Linux.

另一个线程在挂起的上半部分完成后执行所有的下半部分。在高于 Linux 服务器线程的优先级上执行中断线程和下半部分线程,可以避免中断处理程序和 Linux 服务器的并发执行,就像在原生单处理器 Linux 上一样。

Figure 2: Interrupt handling in L4Linux.

图2: L4Linux的中断处理

Since the L4 platform is nearly identical to a bare Pentium architecture platform, we reused most of the device driver support from Linux/x86. As a result, we can employ all Linux/x86 device drivers without modification.

由于 L4 平台与奔腾架构平台几乎完全相同,因此我们重新使用了 Linux/x86 中的大部分设备驱动程序支持。因此,我们无需修改即可使用所有 Linux/x86 设备驱动程序。

Linux 用户进程 Linux User Processes

Each Linux user process is implemented as an L4 task, i. e. an address space together with a set of threads executing in this space. The Linux server creates these tasks and specifies itself as their associated pager. L4 then converts any Linux user-process page fault into an RPC to the Linux server. The server usually replies by mapping and/or unmapping one or more pages of its address space to/from the Linux user process. Thereby, it completely controls the Linux user spaces.

每个 Linux 用户进程都被实现为一个 L4 任务,即一个地址空间和一组在此空间执行的线程。Linux 服务器创建这些任务,并将其自身指定为其关联的分页器。然后,L4 将任何 Linux 用户进程的页面错误转换为对 Linux 服务器的 RPC。服务器通常通过将其地址空间的一个或多个页面映射和/或解映射到 Linux 用户进程中来进行响应。因此,它完全控制了 Linux 的用户空间。

In particular, the Linux server maps the emulation library and the signal thread code (both described in the following paragraphs) into an otherwise unused high-address part of each user address space.

特别地,Linux 服务器将仿真库和信号线程代码(两者都在下面的段落中描述)映射到每个用户地址空间的未使用的高地址部分。

Under our decision to keep Linux changes minimal, the “emulation” library handles only communication with the Linux server and does not emulate Unix functionality on its own. For example, a getpid or read system call is always issued to the server and never handled locally.

根据我们保持 Linux 最小变化的决定,“模拟 “库只处理与 Linux 服务器的通信,而不模拟自身的 Unix 功能。例如,getpid 或 read 系统调用总是向服务器发出,而不是在本地处理。

系统调用机制 System-Call Mechanisms

L4Linux system calls are implemented using remote procedure calls, i. e. IPCs between the user processes and the Linux server. There are three concurrently usable system-call interfaces:

L4Linux 系统调用是通过远程过程调用实现的,即用户进程和 Linux 服务器之间的 IPC。有三个可同时使用的系统调用接口。

a modified version of the standard shared C library libc.so which uses L4 IPC primitives to call the Linux server;

标准共享 C 库 libc.so 的修改版,它使用 L4 IPC 原语来调用 Linux 服务器。

a correspondingly modified version of the libc.a library;

libc.a 库的相应修改版本;

a user-level exception handler (“trampoline”) which emulates the native system-call trap instruction by calling a corresponding routine in the modified shared library.

用户级异常处理程序(“trampoline”),其通过调用修改后的共享库中的相应例程来模拟本机系统调用陷阱指令。

The first two mechanisms are slightly faster, and the third one establishes true binary compatibility. Applications that are linked against the shared library automatically obtain the performance advantages of the first mechanism. Applications statically linked against an unmodified libc suffer the performance degradation of the latter mechanism. All mechanisms can be arbitrarily mixed in any Linux process.

前两种机制稍快,第三种机制建立了真正的二进制兼容性。链接到共享库的应用程序自动获得第一种机制的性能优势。静态链接到未修改的 libc 的应用程序会遭受后一种机制的性能下降。所有机制都可以在任何 Linux 进程中任意混合。

Most of the available Linux software is dynamically linked against the shared library; many remaining programs can be statically relinked against our modified libc.a. We consider therefore the trampoline mechanism to be necessary for binary compatibility but of secondary importance from a performance point of view.

大多数可用的 Linux 软件都是针对共享库动态链接的;剩下的许多程序可以针对我们修改过的 libc.a 静态地重新链接。因此,我们认为 trampoline 机制对于二进制兼容是必要的,但从性能的角度看是次要的。

As required by the architecture-independent part of Linux, the server maps all available physical memory one-to-one into its own address space. Except for a small area used for kernel-internal virtual memory, the server’s virtual address space is otherwise empty. Therefore, all Linux server threads execute in small address spaces which enables improved address-space switching by simulating a tagged TLB on the Pentium processor. This affects all IPCs with the Linux server: Linux system calls, page faults, and hardware interruptions. Avoiding TLB flushes improves IPC performance by at least a factor of 2; factors up to 6 are possible for user processes with large TLB working sets.

正如 Linux 的独立于体系结构的部分所要求的那样,服务器将所有可用的物理内存一对一地映射到自己的地址空间中。除了用于内核内部虚拟内存的一小块区域外,服务器的虚拟地址空间是空的。因此,所有 Linux 服务器线程都在较小的地址空间中执行,从而通过在奔腾处理器上模拟标记的 TLB 来改进地址空间切换。这会影响 Linux 服务器的所有 IPC:Linux 系统调用、页面错误和硬件中断。避免 TLB 刷新至少可以将 IPC 性能提高 2 倍。对于具有大型 TLB 工作集的用户进程,可能达到 6 倍。

The native Linux/x86 kernel always maps the current user address space into the kernel space. Copyin and copyout are done by simple memory copy operations where the required address translation is done by hardware. Surprisingly, this solution turned out to have bad performance implications under L4 (see Section 4.3).

原生的 Linux/x86 内核总是将当前的用户地址空间映射到内核空间。Copyin 和 copyout 是通过简单的内存拷贝操作完成的,其中所需的地址转换是由硬件完成的。令人惊讶的是,这种解决方案在 L4 下被证明有不好的性能影响(见 4.3 节)。

Instead, the L4Linux server uses physical copyin and copyout to exchange data between kernel and user processes. For each copy operation, it parses the server-internal logical page tables to translate virtual user addresses into the corresponding “physical” addresses in the server’s address space and then performs the copy operation using the physical addresses.

相反,L4Linux 服务器使用物理的 copyin 和 copyout 来在内核和用户进程之间交换数据。对于每个复制操作,它解析服务器内部的逻辑页表,将虚拟用户地址转化为服务器地址空间中相应的 “物理 “地址,然后使用物理地址执行拷贝操作。

信号 Signaling

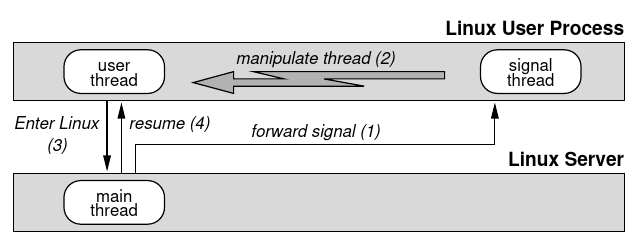

The native Linux kernel delivers signals to user processes by directly manipulating their stack, stack pointer, and instruction pointer. For security reasons, L4 restricts such inter-thread manipulations to threads sharing the same address space. Therefore, an additional signal-handler thread was added to each Linux user process (see Figure 3). Upon receiving a message from the Linux server, the signal thread causes the main thread (which runs in the same address space) to save its state and enter Linux by manipulating the main thread’s stack pointer and instruction pointer.

原生的 Linux 内核通过直接操纵用户进程的堆栈、堆栈指针和指令指针向用户进程传递信号。出于安全考虑,L4 将这种线程间的操作限制在共享同一地址空间的线程。因此,在每个 Linux 用户进程中增加了一个额外的信号处理程序线程(见图 3)。在收到来自 Linux 服务器的消息后,信号线程通过操纵主线程的堆栈指针和指令指针,使主线程(运行在同一地址空间)保存其状态并进入 Linux。

Figure 3: Signal delivery in L4Linux. Arrows denote IPC. Numbers in parentheses indicate the sequence of actions.

图3:L4Linux中的信号传递。箭头表示IPC。括号中的数字表示操作顺序。

The signal thread and the emulation library are not protected against the main thread. However, the user process can only damage itself by modifying them. Global effects of signaling, e. g. killing a process, are implemented by the Linux server. The signal thread only notifies the user process.

信号线程和仿真库不受主线程的保护。然而,用户进程只能通过修改它们来损害自己。信号的全局效果,例如杀死一个进程,是由 Linux 服务器实现的。信号线程只通知用户进程。

调度 Scheduling

All threads mentioned above are scheduled by the L4 μ-kernel’s internal scheduler. This leaves the traditional Linux schedule() operation with little work to do. It only multiplexes the single Linux server thread across the multiple coroutines resulting from concurrent Linux system calls.

上面提到的所有线程都是由 L4 微内核的内部调度器调度的。这使得传统的 Linux schedule()操作几乎没有什么工作可做。它只在并发 Linux 系统调用产生的多个协程之间多路复用单个 Linux 服务器线程。

Whenever a system call completes and the server’s reschedule flag is not set (meaning there is no urgent need to switch to a different kernel coroutine, or there is nothing to do in the kernel), the server resumes the corresponding user thread and then sleeps waiting for a new system-call message or a wakeup message from one of the interrupt handling threads.

每当系统调用完成并且服务器的重调度标志未被设置时(意味着不需要紧急切换到不同的内核协程,或者内核中没有什么可做的),服务器就会恢复相应的用户线程,然后休眠,等待新的系统调用消息或来自某个中断处理线程的唤醒消息。

This behavior resembles the original Linux scheduling strategy. By deferring the call to schedule() until a process’ time slice is exhausted instead of calling it immediately as soon as a kernel activity becomes ready, this approach minimizes the number of coroutine switches in the server and gives user processes the chance to make several system calls per time slice without blocking.

这种行为类似于最初的 Linux 调度策略。通过推迟对 schedule()的调用,直到进程的时间片用完,而不是在内核活动准备就绪时立即调用,这种方法最大限度地减少了服务器中的协程切换的次数,并使用户进程有机会在每个时间片中进行几个系统调用而不阻塞。

However, there can be many concurrently executing user processes, and the actual multiplexing of user threads to the processor is controlled by the L4 μ-kernel and mostly beyond the control of the Linux server. Native L4 uses hard priorities with round-robin scheduling per priority. User-level schedulers can dynamically change the priority and time slice of any thread. The current version of L4Linux uses 10 ms time slices and only 4 of 256 priorities, in decreasing order: interrupt top-half, interrupt bottom-half, Linux kernel, and Linux user process. As a result, Linux processes are currently scheduled round-robin without priority decay. Experiments using more sophisticated user-level schedulers are planned, including one for the classical Unix strategy.

然而,可能有许多并发执行的用户进程,而用户线程对处理器的实际复用是由 L4 微内核控制的,大部分是 Linux 服务器无法控制的。本机 L4 使用硬优先级,每个优先级进行轮流调度。用户级调度器可以动态地改变任何线程的优先级和时间片。当前版本的 L4Linux 使用 10 毫秒的时间片和 256 个优先级中的 4 个,按降序排列:中断上半部分、中断下半部分、Linux 内核和 Linux 用户进程。因此,Linux 进程目前是轮流调度的,没有优先级衰减。计划使用更复杂的用户级调度器进行实验,包括经典 UNIX 策略的实验。

支持标记 TLB 或小空间 Supporting Tagged TLBs or Small Spaces

TLBs are becoming larger to hide the increasing costs of misses relative to processor speed. Depending on the TLB size, flushing a TLB upon address-space switch induces high miss costs for reestablishing the TLB working set when switching back to the original address space. Tagged TLBs, currently offered by many processors, form the architectural basis to avoid unnecessary TLB flushes. For the Pentium processor, small address spaces offer a possibility to emulate TLB tagging. However, frequent context switches — soon, we expect time slices in the order of 10 μs — can also lead to TLB conflicts having effects comparable to flushes. Two typical problems:

TLB 正变得越来越大,以隐藏相对于处理器速度而言不断增加的未命中成本。根据 TLB 大小,在切换回原始地址空间时,在地址空间切换时刷新 TLB 会导致重建 TLB 工作集的高未命中成本。当前由许多处理器提供的标记 TLB,形成了避免不必要的 TLB 刷新的架构基础。对于奔腾处理器,小地址空间提供了模拟 TLB 标记的可能性。然而,频繁的上下文切换(很快,我们预计时间片约为 10μs)也可能导致 TLB 冲突,其影响与刷新相当。两个典型问题:

due to extensive use of huge libraries, the ‘hello-world’ program compiled and linked in the Linux standard fashion has a total size of 80 KB and needs 32 TLB entries to execute;

由于大量使用大型库,以 Linux 标准方式编译和链接的"hello-world"程序的总大小为 80KB,需要 32 个 TLB 条目来执行;

identical virtual allocation of code and data in all address spaces maximizes TLB conflicts between independent applications.

代码和数据在所有地址空间中的相同虚拟分配使独立应用程序之间的 TLB 冲突最大化。

In many cases, the overall effect might be negligible. However, some applications, e. g., a predictable multi-media file system or active routing, might suffer significantly.

在许多情况下,总体影响可能微不足道。然而,一些应用,例如,可预测的多媒体文件系统或主动路由,可能会受到严重影响。

Constructing small, compact, application-dependent address-space layouts can help to avoid the mentioned conflicts. For this reason, L4Linux offers a special library permitting the customization of the code and data used for communicating with the L4Linux server. In particular, the emulation library and the signal thread can be mapped close to the application instead of always mapping to the default high address-space region. By using this library, special servers can be built that can execute in small address spaces, avoiding systematic allocation conflicts with standard Linux processes, while nevertheless using Linux system calls. Examples of such servers are the pagers used for implementing the memory operations described in Section 6.2.

构建小的、紧凑的、依赖于应用程序的地址空间布局可以帮助避免上述冲突。由于这个原因,L4Linux 提供了一个特殊的库,允许定制用于与 L4Linux 服务器通信的代码和数据。特别地,仿真库和信号线程可以被映射到应用程序附近,而不是总是映射到默认的高地址空间区域。通过使用该库,可以构建可以在小地址空间中执行的特殊服务器,从而避免与标准 Linux 进程的系统分配冲突,同时还可以使用 Linux 系统调用。这种服务器的示例是用于实现第 6.2 节中描述的存储器操作的分页器。

4.3 多空间错误 The Dual-Space Mistake

In the engineering sciences, learning about mistakes and dead ends in design is as important as telling success stories. Therefore, this section describes a major design mistake we made in an early version of L4Linux.

在工程科学中,学习设计中的错误和死胡同与讲述成功故事一样重要。因此,本节描述了我们在 L4Linux 的早期版本中所犯的一个重大设计错误。

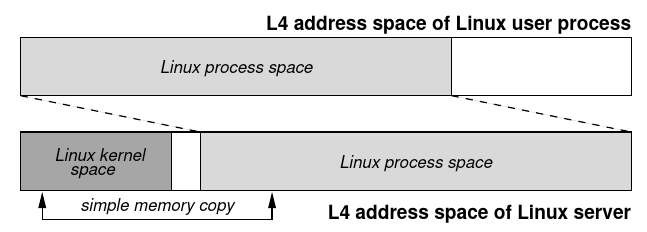

For each Linux process, native Linux/x86 creates a 4 GB address space containing both the user space and the kernel space. This makes it very simple for the Linux kernel to access user data: address translation and page-fault signaling are done automatically by the hardware. We tried to imitate this approach by also mapping the current process’ user address space into the Linux server’s address space (Figure 4). The implementation using a user-level pager was simple. However, we could not map multiple 2.5 GB Linuxprocess spaces simultaneously into the server’s 3 GB address space. Either the user-space mapping had to be changed on each Linux context switch or the server space had to be replicated. Since the first method was considered too expensive, we ended up creating one server address space per Linux process. Code and data of the server were shared through all server spaces. However, the server spaces differed in their upper regions which had mapped the respective Linux user space.

对于每个 Linux 进程,原生 Linux/x86 会创建一个 4GB 的地址空间,包含用户空间和内核空间。这使得 Linux 内核访问用户数据变得非常简单:地址转换和页面错误信号是由硬件自动完成的。我们试图模仿这种方法,将当前进程的用户地址空间映射到 Linux 服务器的地址空间(图 4)。使用用户级分页器的实现很简单。然而,我们无法将多个 2.5GB 的 Linux 进程空间同时映射到服务器的 3GB 地址空间。要么在每次 Linux 上下文切换时改变用户空间的映射,要么必须复制服务器空间。由于第一种方法被认为代价过高,我们最终为每个 Linux 进程创建了一个服务器地址空间。服务器的代码和数据通过所有的服务器空间共享。然而,服务器空间在它们的上层区域是不同的,这些区域映射了各自的 Linux 用户空间。

Figure 4: Copyin/out using hardware address translation in an early version of L4Linux. Arrows denote memory read/write operations.

图4:在L4Linux的早期版本中使用硬件地址转换进行copyin/out。箭头表示内存读/写操作。

Replicating the server space, unfortunately, also required replicating the server thread. To preserve the single-server semantics required by the uniprocessor version of Linux, we thus had to add synchronization to the Linux kernel. Synchronization required additional cycles and turned out to be nontrivial and error-prone.

不幸的是,复制服务器空间,也需要复制服务器线程。为了保持单处理器版本的 Linux 所要求的单服务器语义,我们不得不在 Linux 内核中加入同步功能。同步需要额外的周期,结果证明是不简单的,容易出错的。

Even worse, 3 GB Linux-server spaces made it impossible to use the small-space optimization emulating tagged TLBs. Since switching between user and server therefore always required a TLB flush, the Linux server had to re-establish its TLB working set for every system call or page fault. Correspondingly, the user process was penalized by reloading its TLB working set upon return from the Linux server.

更糟糕的是,3GB 的 Linux 服务器空间使得无法使用模拟标记 TLB 的小空间优化。由于用户和服务器之间的切换总是需要 TLB 刷新,因此 Linux 服务器必须为每个系统调用或页面错误重新建立其 TLB 工作集。相应地,用户进程在从 Linux 服务器返回时由于重新加载其 TLB 工作集而受到惩罚。

We discarded this dual-space approach because it was complicated and not very efficient; getpid took 18 μs instead of 4 μs. Instead, we decided to use the single-space approach described in Section 4.2: only one address space per Linux user process is required and the server space is not replicated. However, virtual addresses have to be translated by software to physical addresses for any copyin and copyout operation.

我们放弃了这种双空间方法,因为它很复杂,而且效率不高。getpid 需要 18μs 而不是 4μs。相反,我们决定使用第 4.2 节中描述的单空间方法:每个 Linux 用户进程只需要一个地址空间,并且不复制服务器空间。然而,对于任何 copyin 和 copyout 操作,虚拟地址必须由软件转换为物理地址。

Ironically, analytical reasoning could have shown us before implementation that the dual-space approach cannot outperform the single-space approach: a hardware TLB miss on the Pentium costs about 25 cycles when the page-table entries hit in the second-level cache because the Pentium MMU does not load page-table entries into the primary cache. On the same processor, translating a virtual address by software takes between 11 and 30 cycles, depending on whether the logical page-table entries hit in the first-level or the second-level cache. In general, hardware translation is nevertheless significantly faster because the TLB caches translations for later reuse. However, the dual-space approach systematically made this reuse for the next system call impossible: due to the large server address space, the TLB was flushed every time the Linux server was called.

具有讽刺意味的是,在实现之前,分析推理可能已经向我们表明,双空间方法无法胜过单空间方法:当页表条目在二级缓存中命中时,奔腾上的硬件 TLB 未命中会花费大约 25 个周期,因为奔腾 MMU 不会将页表条目加载到一级高速缓存中。在同一处理器上,通过软件转换虚拟地址需要 11 到 30 个周期,具体取决于逻辑页表条目是命中一级缓存还是二级缓存。通常,硬件转换仍然明显更快,因为 TLB 缓存转换以供以后重用。然而,双空间方法系统地使这种重用不可能用于下一个系统调用:由于服务器地址空间很大,每次调用 Linux 服务器时都会刷新 TLB。

4.4 产生的 L4Linux 适配 The Resulting L4Linux Adaption

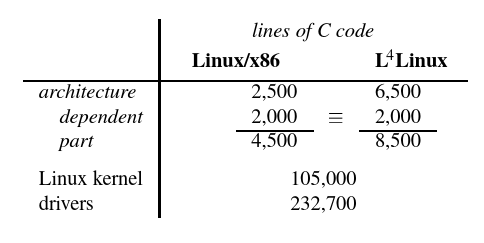

Table 1 compares the source code size of the L4Linux adaption with the size of the native Linux/x86 adaption and the Linux kernel. Comment lines and blank lines are not counted. 2000 lines of the original x86-dependent part could be reused unchanged for the L4 adaption; 6500 new lines of code had to be written. Starting from L4 and Linux, it took about 14 engineer months to build the L4Linux system, stabilize it, and prepare the results presented in this paper.

表 1 比较了 L4Linux 改编的源代码大小与本地 Linux/x86 改编和 Linux 内核的大小。注释行和空行不计算在内。原始 x86 相关部分的 2000 行可以原封不动地重新用于 L4 适配;必须编写 6500 行新代码。从 L4 和 Linux 开始,花了大约 14 个月的时间来构建 L4Linux 系统,使其稳定下来,并准备好本文中的结果。

Table 1: Source-code lines for Linux/x86 and L4Linux.

表1: Linux/x86 and L4Linux 的源代码行数。

We appear to have been successful in our effort of achieving full Linux binary compatibility. We have used the system as a development environment and regularly use such applications as the X Window System, Emacs, Netscape, and X-Pilot. L4Linux appears to be stable, and, as we’ll show, can run such extreme stress tests as the AIM benchmark [2] to completion.

我们似乎已经成功地实现了完全 Linux 二进制兼容性。我们使用该系统作为开发环境,并经常使用 X Window System、Emacs、Netscape 和 X-Pilot 等应用程序。L4Linux 似乎是稳定的,并且,正如我们将要展示的,可以完成诸如 AIM 基准测试[2]这样的极端压力测试。

5 兼容的性能 Compatibility Performance

In this section, we discuss the performance of L4Linux from the perspective of pure Linux applications. The conservative criterion for accepting a μ-kernel architecture is that existing applications are not significantly penalized. So our first question is

在本节中,我们将从纯 Linux 应用程序的角度讨论 L4Linux 的性能。接受微内核架构的保守标准是现有的应用程序不会受到显著的惩罚。所以我们的第一个问题是

What is the penalty for using L4Linux instead of native Linux?

使用 L4Linux 而不是原生 Linux 的惩罚是什么?

To answer it, we ran identical benchmarks on native Linux and L4Linux using the same hardware. Our second question is

为了回答这个问题,我们使用相同的硬件在本地 Linux 和 L4Linux 上运行了相同的基准测试。我们的第二个问题是

Does the performance of the underlying μ-kernel matter?

基础微内核的性能重要吗?

To answer it, we compare L4Linux to MkLinux [10], an OSF-developed port of Linux running on the OSF Mach 43.0 μ-kernel. MkLinux and L4Linux differ basically in the architecture-dependent part, except that the authors of MkLinux slightly modified Linux’s architecture-independent memory system to get better performance on Mach. Therefore, we assume that performance differences are mostly due to the underlying μ-kernel.

为了回答这个问题,我们将 L4Linux 与 MkLinux[10]进行比较,MkLinux 是 OSF 开发的在 OSF Mach 43.0 微内核上运行的 Linux 的移植。MkLinux 和 L4Linux 在依赖于体系结构的部分基本不同,只是 MkLinux 的作者稍微修改了 Linux 的与体系结构无关的内存系统,以便在 Mach 上获得更好的性能。因此,我们认为性能差异主要是由于底层的微内核造成的。

First, we compare L4Linux (which always runs in user mode) to the MkLinux variant that also runs in user mode. Mach is known for slow user-to-user IPC and expensive user-level page-fault handling [5, 21]. So benchmarks should report a distinct difference between L4Linux and MkLinux if the μ-kernel efficiency influences the whole system significantly.

首先,我们将 L4Linux(始终以用户模式运行)与同样以用户模式运行的 MkLinux 变体进行比较。Mach 以缓慢的用户到用户的 IPC 和昂贵的用户级页面错误处理而闻名[5, 21]。因此,如果微内核的效率对整个系统有明显的影响,那么基准测试应该报告 L4Linux 和 MkLinux 之间有明显的差异。

A faster version of MkLinux uses a co-located server running in kernel mode and executing inside the μ-kernel’s address space. Similar to Chorus’ supervisor tasks [32], colocated (in-kernel) servers communicate much more efficiently with each other and with the μ-kernel than user-mode servers do. However, to improve performance, colocation violates the address-space boundaries of a μ-kernel system, which weakens security and safety. So our third question is

MKLinux 的一个更快的版本使用一个在内核模式下运行并在微内核的地址空间内执行的相同位置服务器。与 Chorus 的 Supervisor 任务[32]类似,与用户模式服务器相比,相同位置(内核)服务器之间以及与微内核之间的通信效率更高。然而,为了提高性能,相同位置违反了微内核系统的地址空间边界,这削弱了安全性和安全性。所以我们的第三个问题是

How much does co-location improve performance?

相同位置能在多大程度上提高性能?

This question is evaluated by comparing user-mode L4Linux to the in-kernel version of MkLinux.

这个问题是通过比较用户模式 L4Linux 和 MKLinux 的内核版本来评估的。

5.1 测量方法 Measurement Methodology

To obtain comparable and reproducible performance results, the same hardware was used throughout all measurements, including those of Section 6: a 133 MHz Pentium PC based on an ASUS P55TP4N motherboard using Intel’s 430FX chipset, equipped with a 256 KB pipeline-burst second-level cache and 64 MB of 60 ns Fast Page Mode RAM.

为了获得可比较和可重复的性能结果,所有的测量都使用了相同的硬件,包括第 6 节的测量:基于华硕 P55TP4N 主板的 133MHz 奔腾电脑,使用英特尔的 430FX 芯片组,配备了 256KB 流水线二级缓存和 64MB 的 60ns 快速页面模式内存。

We used version 2 of the L4 μ-kernel.

我们使用第二版的 L4 微内核。

L4Linux is based on Linux version 2.0.21, MkLinux on version 2.0.28. According to the ‘Linux kernel change summaries’ [7], only performance-neutral bug fixes were added to 2.0.28, mostly in device drivers. We consider both versions comparable.

L4Linux 基于 Linux 2.0.21 版本,MkLinux 基于 2.0.28 版本。根据 “Linux 内核更新日志”[7],在 2.0.28 中只增加了性能中立的错误修复,主要是在设备驱动程序中。我们认为这两个版本具有可比性。

Microbenchmarks are used to analyze the detailed behavior of L4Linux mechanisms while macro benchmarks measure the system’s overall performance.

微基准测试用于分析 L4Linux 机制的详细行为,而宏基准测试用于测量系统的整体性能。

Different microbenchmarks give significantly different results when measuring operations that take only 1 to 5 μs. Statistical methods like calculating the standard deviation are misleading: two benchmarks report inconsistent results and both calculate very small standard deviation and high confidence. The reason is that a deterministic system is being measured that does not behave stochastically. For fast operations, most measurement errors are systematic. Some reasons are cache conflicts between measurement code and the system to be measured or miscalculation of the measurement overhead. We, therefore, do not only report standard deviations but show different microbenchmarks. Their differences give an impression of the absolute error. Fortunately, most measured times are large enough to show only small relative deviations. For larger operations, the above-mentioned systematic errors probably add up to a pseudo-stochastic behavior.

当测量仅需 1 至 5μs 的操作时,不同的微基准给出了明显不同的结果。像计算标准差这样的统计方法具有误导性:两个基准报告的结果不一致,并且都计算出非常小的标准差和高置信度。原因是被测量的确定性系统的行为不是随机的。对于快速操作,大多数测量误差是系统性的。一些原因是测量代码与要测量的系统之间的缓存冲突或测量开销的计算错误。因此,我们不仅报告标准偏差,还展示不同的微基准。他们的差异给人一种绝对误差的印象。幸运的是,大多数测量时间足够大,只显示出很小的相对偏差。对于较大的操作,上述的系统误差可能加起来就是一个伪随机行为。

5.2 微基准 Microbenchmarks

For measuring the system-call overhead, getpid, the shortest Linux system call, was examined. To measure its cost under ideal circumstances, it was repeatedly invoked in a tight loop. Table 2 shows the consumed cycles and the time per invocation derived from the cycle numbers. The numbers were obtained using the cycle counter register of the Pentium processor. L4Linux needs approximately 300 cycles more than native Linux. An additional 230 cycles are required whenever the trampoline is used instead of the shared library. MkLinux shows 3.9 times (in-kernel) or 29 times (user mode) higher system-call costs than L4Linux using the shared library. Unfortunately, L4Linux still needs 2.4 times as many cycles as native Linux.

为了测量系统调用开销,研究了最短的 Linux 系统调用 getpid。为了在理想情况下衡量其成本,它在一个紧密的循环中被反复调用。表 2 显示了消耗的周期和从周期数得出的每次调用的时间。这些数字是通过奔腾处理器的周期计数寄存器获得的。L4Linux 需要比本地 Linux 多大约 300 个周期。每当使用 trampoline 而不是共享库时,需要额外的 230 个周期。MkLinux 显示出比使用共享库的 L4Linux 高 3.9 倍(内核中)或 29 倍(用户模式)的系统调用开销。不幸的是,L4Linux 仍然需要 2.4 倍于原生 Linux 的周期。

| System | Time | Cycles |

|---|---|---|

| Linux | 1.68μs | 223 |

| L4Linux | 3.95μs | 526 |

| L4Linux(trampoline) | 5.66μs | 753 |

| MkLinux in-kernel | 15.41μs | 2050 |

| MkLinux user | 110.60μs | 14710 |

Table 2: getpid system-call costs on the different implementations. (133 MHz Pentium)

表2: getpid系统调用在不同实现上的开销。(133 MHz 奔腾)

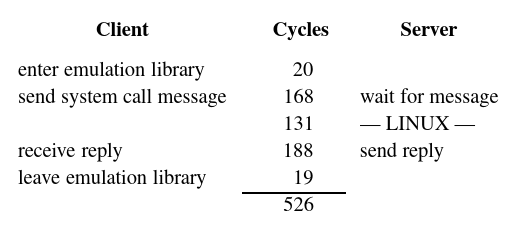

Figure 5: Cycles spent for getpid in L4Linux. (133 MHz Pentium)

图4: L4Linux上的getpid周期花费。(133 MHz 奔腾)

Figure 5 shows a more detailed breakdown of the L4Linux overhead. Under native Linux, the basic architectural overhead for entering and leaving kernel mode is 82 cycles, the bare hardware costs. In L4Linux, it corresponds to two IPCs taking 356 cycles in total. After deducting the basic architectural overhead from the total system-call costs, 141 cycles remain for native Linux, and 170 cycles for L4Linux. The small difference in both values indicates that indeed IPC is the major cause of additional costs in L4Linux.

图 5 显示了 L4Linux 开销的更详细分解。在原生 Linux 下,进入和离开内核模式的基本架构开销是 82 个周期,即裸硬件成本。在 L4Linux 中,它对应于两个 IPC,总共需要 356 个周期。从总的系统调用开销中扣除基本的架构开销后,原生 Linux 还剩下 141 个周期,L4Linux 还剩下 170 个周期。两个值的微小差异表明 IPC 确实是 L4Linux 中额外成本的主要原因。

When removing the part called LINUX in Figure 5, the 4L Linux overhead code remains. It uses 45 cache lines, 9% of the first-level cache, including the cache L4 needs for IPC.

当删除图 5 中调用 Linux 的部分时,L4Linux 开销代码仍然存在。它使用 45 个缓存行,占一级缓存的 9%,包括 L4 所需的 IPC 缓存。

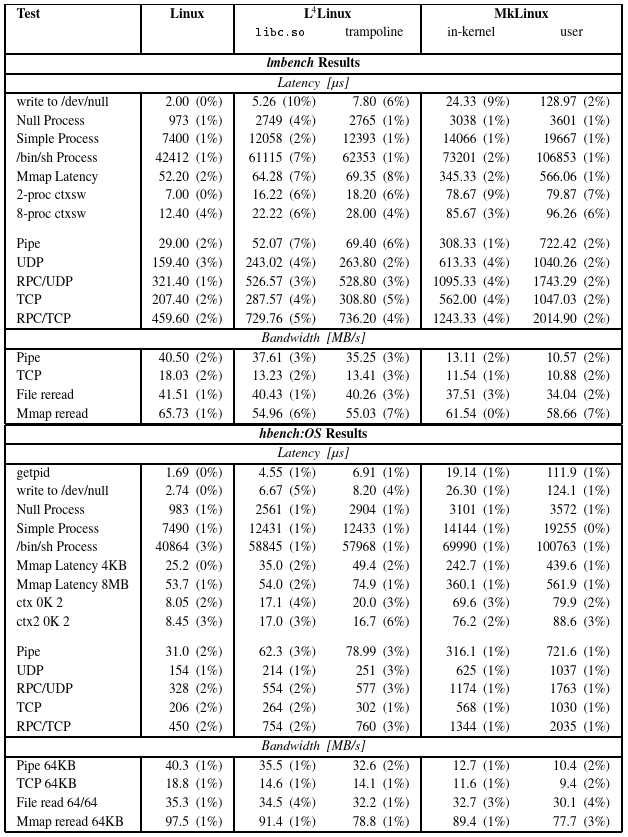

The lmbench [29] microbenchmark suite measures basic operations like system calls, context switches, memory accesses, pipe operations, network operations, etc. by repeating the respective operation a large number of times. lmbench’s measurement methods have recently been criticized by Brown and Seltzer [6]. Their improved hbench:OS microbenchmark suite covers a broader spectrum of measurements and measures short operations more precisely. Both benchmarks have been developed to compare different hardware from the OS perspective and therefore also include a variety of OS-independent benchmarks, in particular measuring the hardware memory system and the disk. Since we always use the same hardware for our experiments, we present only the OS-dependent parts. The hardware-related measurements gave indeed the same results on all systems.

lmbench[29]微基准套件通过大量重复各自的操作来测量诸如系统调用、上下文切换、内存访问、管道操作、网络操作等基本操作。lmbench 的测量方法最近被 Brown 和 Seltzer[6]批评。他们改进的 hbench:OS 微基准套件涵盖了更广泛的测量范围,并且更精确地测量短操作。这两个基准都是为了从操作系统的角度比较不同的硬件而开发的,因此也包括各种与操作系统无关的基准,特别是测量内存系统和磁盘等硬件。由于我们在实验中总是使用相同的硬件,我们只介绍与操作系统相关的部分。与硬件有关的测量在所有的系统上确实给出了相同的结果。

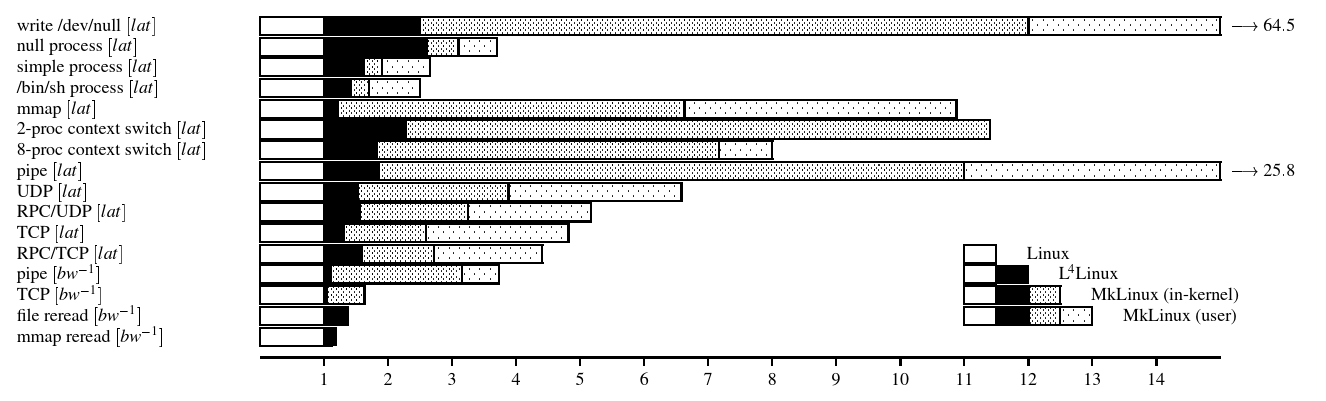

Table 3 shows the selected results of lmbench and hbench. It compares native Linux, L4Linux with and without trampoline, and both versions of MkLinux. Figure 6 plots the slow4down of L4Linux, co-located and user-mode MkLinux, normalized to native Linux. Both versions of MkLinux have a much higher penalty than L4Linux. Surprisingly, the effect of co-location is rather small compared to the effect of using L4. However, even the L4Linux penalties are not as low as we hoped.

表 3 显示了 lmbench 和 hbench 的选定结果。它比较了原生 Linux、有 trampoline 和无 trampoline 的 L4Linux,以及两个版本的 MkLinux。图 6 显示了 L4Linux、相同位置和用户模式的 MkLinux 的减速情况,并将其与原生 Linux 对比。两个版本的 MkLinux 的惩罚都比 L4Linux 高得多。令人惊讶的是,与使用 L4 的效果相比,相同位置的效果相当小。然而,即使是 L4Linux 的惩罚也没有我们希望的那么低。

5.3 宏基准 Macrobenchmarks

Figure 6: lmbench results, normalized to native Linux. These are presented as slowdowns: a shorters bar is a better result. [lat] is a latency measurement, [bw-1] the inverse of a bandwidth one. Hardware is a 133MHz Pentium.

图6:lmbench的结果,标准化为原生Linux。这些结果是以减少的速度表示的:条形越短说明结果越好。[lat]是延迟测量,[bw-1]是带宽的倒数。硬件是133MHz的Pentium。

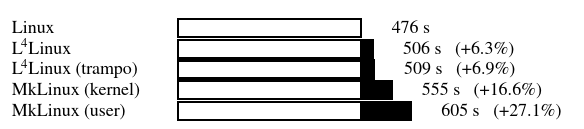

Figure 7: Real time for compiling the Linux Server. (133 MHz Pentium)

图7:编译Linux服务器的实时时间。(133 MHz 奔腾)

In the first macro benchmark experiment, we measured the time needed to recompile the Linux server (Figure 7). L4Linux was 6–7% slower than native Linux but 10–20% faster than both MkLinux versions.

在第一个宏基准测试实验中,我们测量了重新编译 Linux 服务器所需的时间(图 7)。L4Linux 比本机 Linux 慢 6–7%,但比两个 MkLinux 版本都快 10–20%。

A more systematic evaluation was done using the commercial AIM multiuser benchmark suite VII. It uses Load Mix Modeling to test how well multiuser systems perform under different application loads [2]. (The AIM benchmark results presented in this paper are not certified by AIM Technology.)

使用商业 AIM 多用户基准测试套件 VII 进行了更系统的评估。它使用负载混合模型来测试多用户系统在不同应用程序负载下的性能[2]。(本文提供的 AIM 基准测试结果未经 AIM 技术认证。)

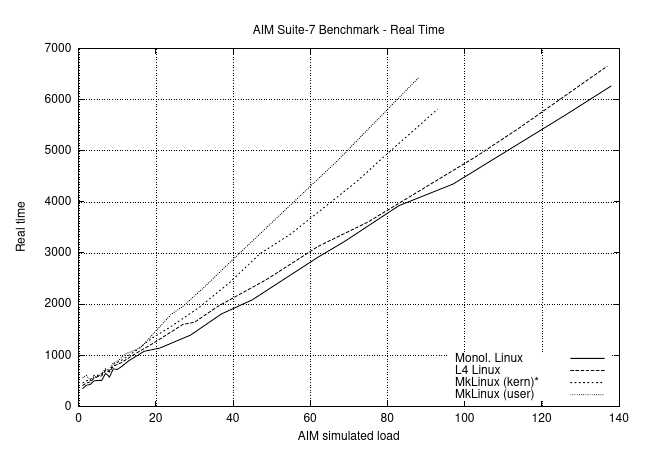

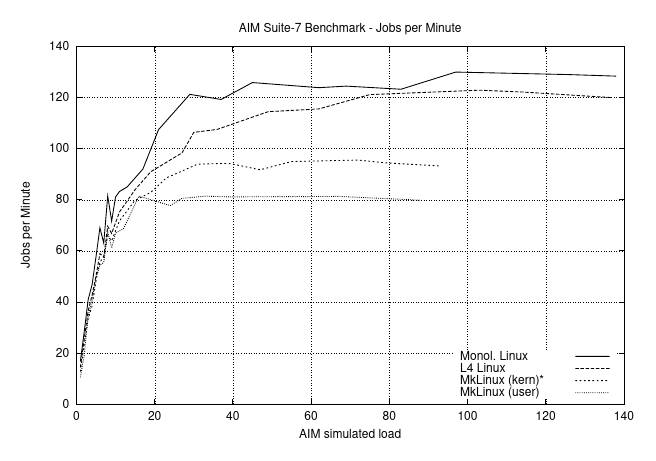

AIM uses the shared libc.so so that the trampoline overhead is automatically avoided. Depending on simulated load, Figures 8 and 9 show the required time and the achieved throughput (jobs per minute) for native Linux, L4Linux, and both MkLinux versions. The AIM benchmark successively increases the load until the maximum throughput of the system is determined. (For this reason, it stops at a lower load for MkLinux than for L4Linux and native Linux.)

AIM 使用共享的 libc.so,因此自动避免了 trampoline 的开销。根据模拟的负载,图 8 和图 9 显示了本地 Linux、L4Linux 和 MkLinux 两个版本所需的时间和实现的吞吐量(每分钟作业)。AIM 基准测试连续增加负载,直到确定系统的最大吞吐量。(因此,与 L4Linux 和原生 Linux 相比,MkLinux 的停止负载较低)。

For native Linux, AIM measures a maximum load of 130 jobs per minute. L4Linux achieves 123 jobs per minute, 95% of native Linux. The corresponding numbers for user-mode MkLinux are 81 jobs per minute, 62% of native Linux, and 95 (73%) for the in-kernel version.

对于本地 Linux,AIM 测量的最大负载为每分钟 130 个作业。L4Linux 实现了每分钟 123 个作业,是本地 Linux 的 95%。用户模式的 MkLinux 的相应数字是每分钟 81 个作业,是原生 Linux 的 62%,内核内版本是 95(73%)。

Averaged over all loads, L4Linux is 8.3% slower than native Linux, and 6.8% slower at the maximum load. This is consistent with the 6–7% we measured for recompiling Linux.

所有负载的平均值,L4Linux 比原生 Linux 慢 8.3%,在最大负载时慢 6.8%。这与我们在重新编译 Linux 时测得的 6-7% 一致。

User-mode MkLinux is on average 49% slower than native Linux, and 60% at its maximum load. The co-located in-kernel version of MkLinux is 29% slower on average than Linux, and 37% at maximum load.

用户模式 mklinux 平均比原生 Linux 慢 49%,在最大负载时慢 60%。MKLinux 的相同位置版本平均比 Linux 慢 29%,在最大负载时慢 37%。

5.4 分析 Analysis

The macro benchmarks answer our first question. The current implementation of L4Linux comes reasonably close to the behavior of native Linux, even under high load. Typical penalties range from 5% to 10%.

宏基准测试回答了我们的第一个问题。L4Linux 的当前实现相当接近原生 Linux 的行为,即使在高负载下也是如此。典型的惩罚范围是 5%到 10%。

Figure 8: AIM Multiuser Benchmark Suite VII. Real time per benchmark run depending on AIM load units. (133 MHz Pentium)

图8:AIM多用户基准测试套件VII。每个基准运行的实时时间取决于AIM负载单位。(133 MHz奔腾)

Figure 9: AIM Multiuser Benchmark Suite VII. Jobs completed per minute depending on AIM load units. (133 MHz Pentium)

图9:AIM多用户基准测试套件VII。每分钟完成的作业数取决于AIM负载单位。(133 MHz奔腾)

Table 3: Selected OS-dependent lmbench and hbench-OS results. (133 MHz Pentium.) Standard deviations are shown in parentheses.

表3:部分依赖操作系统的lmbench和hbench-OS结果。(133 MHz奔腾)括号内为标准差。

Both macro and microbenchmarks indicate that the performance of the underlying μ-kernel matters. We are particularly confident in this result because we did not compare different Unix variants but two μ-kernel implementations of the same OS.

宏基准测试和微基准测试都表明底层微内核的性能很重要。我们对这个结果特别有信心,因为我们没有比较不同的 UNIX 变体,而是比较了同一操作系统的两个微内核实现。

Furthermore, all benchmarks illustrate that co-location on its own is not sufficient to overcome performance deficiencies when the basic μ-kernel does not perform well. It would be an interesting experiment to see whether introducing colocation in L4 would have a visible effect or not.

此外,所有基准测试都表明,当基础微内核性能不佳时,相同位置本身不足以克服性能缺陷。看看在 L4 中引入相同位置是否会有明显的效果,这将是一个有趣的实验。

6 扩展性能 Extensibility Performance

No customer would use a μ-kernel if it offered only the classical Unix API, even if the μ-kernel imposed zero penalties on the OS personality on top. So we have to ask for the “added value” the μ-kernel gives us. One such is that it enables specialization (improved implementation of special OS functionality [31]) and buys us extensibility, i. e., permits the orthogonal implementation of new services and policies that are not covered by and cannot easily be added to a conventional workstation OS. Potential application fields are databases, real-time, multi-media, and security.

如果微内核只提供经典的 Unix API,没有客户会使用它,即使不会有任何性能惩罚。因此,我们必须问一下微内核给我们带来的 “附加价值”。其中之一是它支持专门化(改进了特殊操作系统功能的实现[31]),并为我们赢得了可扩展性,也就是说,允许新服务和策略的正交实现,这些服务和策略是传统的工作站操作系统所不具备的,也不容易被添加到传统的工作站操作系统中。潜在的应用领域是数据库、实时、多媒体和安全。

In this section, we are interested in the corresponding performance aspects for L4 with L4Linux running on top. We ask three questions:

在本节中,我们对 L4 与 L4Linux 运行在上面的相应性能方面感兴趣。我们提出三个问题。

Can we add services outside L4Linux to improve performance by specializing in Unix functionality?

我们是否可以在 L4Linux 之外增加服务,通过专攻 Unix 功能来提高性能?

Can we improve certain applications by using native μkernel mechanisms in addition to the classical API?

除了经典 API 之外,我们是否可以通过使用本机微内核机制来改进某些应用程序?

Can we achieve high performance for non-classical, Unix-incompatible systems coexisting with L4Linux?

对于与 L4Linux 共存的非经典、Unix 不兼容的系统,我们能否实现高性能?

Currently, these questions can only be discussed based on selected examples. The overall quantitative effects on large systems remain still unknown. Nevertheless, we consider the “existence proofs” of this section to be a necessary precondition to answer the aforementioned questions positively for a broad variety of applications.

目前,这些问题只能根据选定的例子来讨论。对大型系统的整体定量影响仍然是未知的。尽管如此,我们认为本节的 “存在性证明 “是积极回答上述问题的必要前提,以利于广泛的应用。

6.1 管道和 RPC Pipes and RPC

It is widely accepted that IPC can be implemented significantly faster in a μ-kernel environment than in classical monolithic systems. However, applications have to be rewritten to make use of it. Therefore, in this section, we compare classical Unix pipes, pipe emulations through μkernel IPC, and blocking RPC to get an estimate for the cost of emulation on various levels.

人们普遍认为,在微内核环境中实现 IPC 的速度明显快于传统的宏内核系统。但是,必须重写应用程序才能使用它。因此,在这一节中,我们比较了经典的 Unix 管道、通过微内核 IPC 进行的管道仿真以及阻塞式 RPC,以估算不同级别的模拟成本。

We compare four variants of data exchange. The first is the standard pipe mechanism provided by the Linux kernel: (1) runs on native Linux/x86; (1a) runs on L4Linux and uses the shared library, (1b) uses the trampoline mechanism instead; (1c) runs on the user-mode server of MkLinux, and (1d) on the co-located MkLinux server.

我们比较了数据交换的四种变体。第一种是 Linux 内核提供的标准管道机制:(1)在原生 Linux/x86 上运行;(1a)在 L4Linux 上运行并使用共享库,(1b)使用 trampoline 机制代替;(1c)在 MkLinux 的用户模式服务器上运行,以及(1d)在相同位置的 MkLinux 服务器上。

Although the next three variants run on L4Linux, they do not use the Linux server’s pipe implementation. Asynchronous pipes on L4 (2) is a user-level pipe implementation that runs on bare L4, uses L4 IPC for communication, and needs no Linux kernel. The emulated pipes are POSIX compliant, except that they do not support signaling. Since L4 IPC is strictly synchronous, an additional thread is responsible for buffering and cross-address-space communication with the receiver.

尽管接下来的三个变体都运行在 L4Linux 上,但它们并不使用 Linux 服务器的管道实现。L4 上的异步管道(2)是一个用户级的管道实现,运行在裸露的 L4 上,使用 L4 IPC 进行通信,不需要 Linux 内核。模拟的管道符合 POSIX 标准,只是不支持信号。由于 L4 IPC 是严格的同步的,一个额外的线程负责缓冲和与接收器的跨地址空间通信。

Synchronous RPC (3) uses blocking IPC directly, without buffering data. This approach is not semantically equivalent to the previous variants but provides blocking RPC semantics. We include it in this comparison because applications using RPC in many cases do not need asynchronous pipes, so they can benefit from this specialization.

同步 RPC(3)直接使用阻塞 IPC,而不缓冲数据。此方法在语义上不等同于前面的变体,但提供了阻塞 RPC 语义。我们之所以将其包括在此比较中,是因为在许多情况下使用 RPC 的应用程序不需要异步管道,因此它们可以从此专门化中受益。

For synchronous mapping RPC (4), the sender temporarily maps pages into the receiver’s address space. Since mapping is a special form of L4 IPC, it can be freely used between user processes and is secure: mapping requires agreement between sender and receiver and the sender can only map its pages. The measured times include the cost for subsequent unmapping operations. For hardware reasons, latency here is measured by mapping one page, not one byte. The bandwidth measurements map aligned 64 KB regions.

对于同步映射 RPC(4),发送方将页面临时映射到接收方的地址空间。由于映射是 L4 IPC 的一种特殊形式,因此它可以在用户进程之间自由使用,并且是安全的:映射需要发送方和接收方之间的协议,并且发送方只能映射其页面。测量的时间包括后续取消映射操作的成本。由于硬件原因,这里的延迟是通过映射一个页面而不是一个字节来测量的。带宽测量映射对齐的 64 KB 区域。

For measurements, we used the corresponding lmbench routines. They measure latency by repeatedly sending 1 byte back and forth synchronously (ping-pong) and bandwidth by sending about 50 MB in 64 KB blocks to the receiver. The results of Table 4 show that the latency and the bandwidth of the original monolithic pipe implementation (1) on native Linux can be improved by emulating asynchronous pipe operations on synchronous L4 IPC (2). Using synchronous L4 RPC (2) requires changes to some applications but delivers a factor of 6 improvements in latency over native Linux.

对于测量,我们使用了相应的 lmbench 程序。它们通过重复同步地来回发送 1 个字节(ping-pong)来测量延迟,并通过将大约 50MB 的 64KB 块发送到接收器来测量带宽。表 4 的结果显示,通过模拟同步 L4 IPC(2)上的异步管道操作,可以改善原生 Linux 上原始单片机管道实现(1)的延迟和带宽。使用同步 L4 RPC(2)需要对一些应用程序进行修改,但在延迟方面比原生 Linux 提高了 6 倍。

| System | Latency | Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Linux Pipe | 29μs | 41 MB/s |

| (1a) L4Linux pipe | 46μs | 40MB/s |

| (1b) L4Linux (trampoline) pipe | 56μs | 38MB/s |

| (1c) MkLinux (user) pipe | 722μs | 10MB/s |

| (1d) MkLinux (in-kernel) pipe | 316μs | 13MB/s |

| (2) L4 pipe | 22μs | 48-70MB/s |

| (3) synchronous L4 RPC | 5μs | 65-105MB/s |

| (4) synchronous mapping RPC | 12μs | 2470-2900MB/s |

Table 4: Pipe and RPC performance. (133 MHz Pentium.) Only communication costs are measured, not the costs to generate or consume data.

表4:管道和RPC性能。(133 MHz奔腾)只测量通信成本,不测量生成或消耗数据的成本。

Since the bandwidth measurement moves 64 KB chunks of data, its performance is determined by the memory hardware, in particular by the direct-mapped second-level cache. As proposed by Jonathan Shapiro [35], L4 IPC simulates a write-allocate cache by prereading the destination area when copying longer messages. In the best case, Linux allocates pages such that source and destination do not overlap in the cache; in the worst case, the copy operation flushes every data before its next usage. A similar effect can be seen for L4 pipes.

由于带宽测量移动 64KB 的数据块,其性能由内存硬件决定,特别是由直接映射的二级缓存决定。正如 Jonathan Shapiro[35]所提出的,L4 IPC 通过在复制较长消息时预读目标区域来模拟写分配缓存。在最好的情况下,Linux 分配页面时,缓存中的源和目标不会重叠;在最坏的情况下,复制操作会在下次使用之前刷新所有数据。在 L4 管道中也可以看到类似的效果。

Linux copies data twice for pipe communication but uses only a fixed one-page buffer in the kernel. Since, for long streams, reading/writing this buffer always hits in the primary cache, this special double copy performs nearly as fast as a single bcopy. The deviation is small because the lmbench program always sends the same 64 KB and the receiver never reads the data from memory. As a consequence, the source data never hits the primary cache, always hits the secondary cache and the destination data always misses both caches since the Pentium caches do not allocate cache lines on write misses.

Linux 为管道通信复制数据两次,但在内核中只使用固定的一页缓冲区。因为对于长数据流来说,读取/写入此缓冲区总是命中主缓存,这种特殊的双倍拷贝的执行速度几乎与单个 bcopy 一样。偏差很小,因为 lmbench 程序总是发送相同的 64KB 的数据,而且接收方从未从内存中读取数据。因此,源数据永远不会命中主高速缓存,总是命中辅助高速缓存,并且目标数据总是在两个高速缓存上都未命中,因为奔腾的高速缓存不会在写入未命中时分配高速缓存行。

Method (4) achieves a nearly infinite bandwidth due to the low costs of mapping. To prevent misinterpretations: infinite bandwidth only means that the receiver gets the data without a communication penalty. Memory reads are still required to use the data.

由于映射的低成本,方法(4)实现了几乎无限的带宽。为了防止误解:无限带宽只意味着接收器在没有通信损失的情况下获得数据。仍然需要内存读取才能使用数据。

6.2 虚拟内存操作 Virtual Memory Operations

Table 5 shows the times for selected memory management operations. The first experiment belongs to the extensibility category, i. e., it tests a feature that is not available under pure Linux: Fault measures the time needed to resolve a page fault by a user-defined pager in a separate user address space that simply maps an existing page. The measured time includes the user instruction, page fault, notification of the pager by IPC, mapping a page, and completing the original instruction.

表 5 显示了所选内存管理操作的时间。第一个实验属于可扩展性范畴,也就是说,它测试在纯 Linu 下没有的功能:错误测量的是在一个单独的用户地址空间中,由用户定义的分页器解决页面错误所需的时间,该用户地址空间只是映射现有页面。测量的时间包括用户指令、页面错误、IPC 通知分页器、映射页面和完成原始指令。

| L4 | Linux | |

|---|---|---|

| Fault | 6.2μs | n/a |

| Trap | 3.4μs | 12μs |

| Appel1 | 12μs | 55μs |

| Appel2 | 10μs | 44μs |

Table 5: Processor time for virtual-memory benchmarks. (133 MHz Pentium)

表5:虚拟内存基准测试的处理器时间。(133 MHz奔腾)

The next three experiments are taken from Appel and Li [3]. We compare the Linux version with an implementation using native L4 mechanisms. Trap measures the latency between a write operation to a write-protected page and the invocation of the related exception handler. Appel1 measures the time to access a randomly selected protected page where the fault handler unprotects the page, protects some other page, and resumes the faulting access (’trap+prot1+unprot’). Appel2 first protects 100 pages, then accesses them in a random sequence where the fault handler only unprotects the page and resumes the faulting operation (‘protN+trap+unprot’). For L4, we reimplemented the fault handlers by associating a specialized pager to the thread executing the test. The new pager handles resolvable page faults as described above and propagates unresolvable page faults to the Linux server.

接下来的三个实验来自 Appel 和 Li[3]。我们将 Linux 版本与使用本机 L4 机制的实现进行比较。陷阱测量对写保护页的写操作和调用相关异常处理程序之间的延迟。Appel1 测量访问随机选择的受保护页面的时间,其中错误处理程序取消对该页面的保护,保护其他一些页面,并恢复错误访问(’trap+prot1+unprot’)。Appel2 首先保护 100 个页面,然后以随机顺序访问它们,其中错误处理程序仅取消保护该页面并恢复错误操作(‘protn+trap+unprot’)。对于 L4,我们通过将专门的分页程序关联到执行测试的线程来重新实现错误处理程序。新的分页程序如上所述处理可解析的页面错误,并将不可解析的页面错误传播到 Linux 服务器。

6.3 缓存分区 Cache Partitioning

Real-time applications need memory management different from the one Linux implements. L4’s hierarchical user-level pagers allow both the L4Linux memory system and a dedicated real-time one to be run in parallel. This section evaluates how well this works in practice.

实时应用程序需要不同于 Linux 实现的内存管理。L4 的分层用户级分页器允许 L4Linux 内存系统和专用实时系统并行运行。本节评估这在实践中的效果。

In real-time systems, the optimization criterion is not the average but the worst-case execution time. Since a real-time task has to meet its deadline under all circumstances, sufficient resources for the worst case must always be allocated and scheduled. The real-time load is limited by the sum of worst-case execution times, worst-case memory consumption, etc. In contrast to conventional applications, the average behavior is only of secondary importance.

在实时系统中,优化的标准不是平均时间,而是最坏情况下的执行时间。由于实时任务在任何情况下都必须满足其最后期限,因此必须始终为最坏情况分配和安排足够的资源。实时负载受限于最坏情况下的执行时间、最坏情况下的内存消耗等的总和。与传统应用相比,平均行为只是次要的。

All real-time applications rely on predictable scheduling. Unfortunately, memory caches make it very hard to schedule processor time predictably. If two threads use the same cache lines, executing both threads interleaved increases the total time not only by the context-switching costs but additionally by the cache-interference costs which are much harder to predict. If the operating system does not know or cannot control the cache usage of all tasks, the cache-interference costs are unpredictable.

所有实时应用程序都依赖于可预测的调度。不幸的是,内存缓存使得可预测地调度处理器时间变得非常困难。如果两个线程使用相同的高速缓存行,则交错执行两个线程不仅会因上下文切换成本而增加总时间,而且还会因更难预测的高速缓存干扰成本而增加总时间。如果操作系统不知道或不能控制所有任务的高速缓存使用,则高速缓存干扰成本是不可预测的。

In [26], we described how a main-memory manager (a pager) on top of L4 can be used to partition the second-level cache between multiple real-time tasks and to isolate real-time from timesharing applications.

在[26]中,我们描述了如何使用 L4 上的主存管理器(分页器)在多个实时任务之间划分二级缓存,并将实时应用程序与分时应用程序隔离。

In one of the experiments, a 64x64-matrix multiplication is periodically interrupted by a synthetic load that maximizes cache conflicts. Uninterrupted, the matrix multiplication takes 10.9 ms. Interrupted every 100 μs, its worst-case execution time is 96.1 ms, a slowdown by a factor of 8.85.

在其中一个实验中,一个 64x64 的矩阵乘法被一个合成负载周期性地打断,该负载使缓存冲突最大化。不间断地,矩阵乘法需要 10.9 毫秒。每 100 微秒中断一次,其最坏情况下的执行时间为 96.1 毫秒,慢了 8.85 倍。

In the cache-partitioning case, the pager allocates 3 secondary-cache pages exclusively to the matrix multiplication out of a total of 64 such pages. This neither avoids primary-cache interference nor secondary-cache misses for the matrix multiplication whose data working set is 64 KB. However, by avoiding secondary-cache interference with other tasks, the worst-case execution time is reduced to 24.9 ms, a slowdown of only 2.29. From a real-time perspective, the partitioned matrix multiplication is nearly 4 times “faster” than the unpartitioned one.

在高速缓存分区的情况下,分页器从总共 64 个这样的页面中专门分配 3 个二级高速缓存页面给矩阵乘法。对于数据工作集为 64KB 的矩阵乘法,这既不能避免主缓存干扰,也不能避免次缓存未命中。然而,通过避免二级高速缓存对其他任务的干扰,最坏情况下的执行时间减少到 24.9ms,仅减慢 2.29。从实时的角度来看,分区矩阵乘法比未分区矩阵乘法"快"近 4 倍。

Allocating resources to the real-time system degrades timesharing performance. However, the described technique enables customized dynamic partitioning of system resources between real-time and timesharing systems.

将资源分配给实时系统会降低分时性能。然而,所描述的技术能够在实时系统和分时系统之间实现系统资源的自定义动态分区。

6.4 分析 Analysis

Pipes and some VM operations are examples of improving Unix-compatible functionality by using μ-kernel primitives. RPC and the use of user-level pagers for VM operations illustrate that Unix-incompatible or only partially compatible functions can be added to the system that outperforms implementations based on the Unix API.

管道和一些虚拟内存操作是通过使用微内核原语来改进 UNIX 兼容功能的示例。RPC 和用于虚拟内存操作的用户级分页器的使用表明,可以将 UNIX 不兼容或仅部分兼容的功能添加到系统中,这优于基于 UNIX API 的实现。

The real-time memory management shows that a μ-kernel can offer good possibilities for coexisting systems that are based on completely different paradigms. There is some evidence that the μ-kernel architecture enables to implementation of high-performance non-classical systems cooperating with a classical timesharing OS.

实时内存管理表明,微内核可以为基于完全不同范式的共存系统提供良好的可能性。有一些证据表明,微架构能够实现高性能的非经典系统与经典的分时操作系统合作。

7 其他基本概念 Alternative Basic Concepts

In this section, we address questions about whether a mechanism lower level than IPC or a grafting model could improve the μ-kernel performance.

在本节中,我们将讨论比 IPC 更低级别的机制或嫁接模型是否可以提高微内核性能。

7.1 受保护控制转移 Protected Control Transfers

VM/370 [28] was built on the paradigm of virtualizing and multiplexing the underlying hardware. Recently, Engler, Kaashoek, and O’Toole [12] applied a similar principle to μ-kernels. Instead of complete one-to-one virtualization of the hardware (which had turned out to be inefficient in VM/370), they support selected hardware-similar primitives and claim: “The lower the level of a primitive, the more efficiently it can be implemented and the more latitude it grants to implementors of higher-level abstractions.” Instead of implementing abstractions like IPC or address spaces, only hardware mechanisms such as TLBs should be multiplexed and exported securely.

VM/370[28]是建立在对底层硬件进行虚拟化和复用的范式上的。最近,Engler、Kaashoek 和 O’Toole[12]将类似的原理应用于微内核。他们没有对硬件进行完全的一对一的虚拟化(这在 VM/370 中被证明是低效的),而是支持选定的类似硬件的原语,并声称:“原语的级别越低,它就越能被有效地实现,并给予更高级别的抽象的实现者更多的自由度。” 而不是实现像 IPC 或地址空间这样的抽象,只有像 TLB 这样的硬件机制应该被复用和安全地导出。

From this point of view, IPC might be too high-level an abstraction to be implemented with optimum efficiency. Instead, a protected control transfer (PCT) as proposed in [12] might be faster. PCT is similar to a hardware interrupt: a parameterless cross-address-space procedure call via a callee-defined call gate.

从这个角度来看,IPC 可能是一种过于高级的抽象,无法以最佳效率实现。相反,[12]中提出的受保护控制转移(PCT)可能更快。PCT 类似于硬件中断:通过被调用者定义的调用入口进行的无参数跨地址空间过程调用。

Indeed, when we started the design of L4/Alpha, we first had the impression that PCT could be implemented more efficiently than simple IPC. We estimated 30 cycles against 80 cycles (no TLB or cache misses assumed).

事实上,当我们开始设计 L4/Alpha 时,我们第一次有了这样的印象,即 PCT 可以比简单的 IPC 更有效地实现。我们估计 30 个周期,而不是 80 个周期(假设没有 TLB 或缓存未命中)。

However, applying techniques similar to those used for IPC-path optimization in the Pentium version of L4, we ended up with 45 cycles for IPC versus 38 cycles for PCT on the Alpha processor. A detailed description can be found in table 6. The 7 additional cycles required for IPC provide synchronization, message transfer, and stack allocation. Most server applications need these features and must therefore spend the cycles additionally to the PCT costs. Furthermore, IPC makes 1-to-n messages simple since it includes starting the destination threads.

然而,应用与奔腾版 L4 的 IPC 路径优化类似的技术,我们最终在 Alpha 处理器上的 IPC 为 45 个周期,而 PCT 为 38 个周期。详细描述见表 6。IPC 需要的 7 个额外周期提供了同步、消息传输和堆栈分配。大多数服务器应用程序需要这些功能,因此必须在 PCT 成本之外再花费这些周期。此外,IPC 使 1 对 n 消息变得简单,因为它包括启动目标线程。

| Operation | PCT | IPC | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| enter PAL mode | 5 | 5 | |

| open frame | 7 | 7 | setup stack frame to allow multiple interrupts, TLB misses and simplify thread switching |

| send/receive | 0.5 | determine | |

| test receiver | 2 | 2 | |

| test no chief xfer | 0.5 | ||

| receiver accepts? | 1 | can we do the transfer | |

| set my rcv parameters | 1 | ||

| save rcv parameter | 2 | perform the receive | |

| verify queuing status | 1 | to set wakeup-queueing invalid, if timeout NEVER | |

| context switch | 10 | 10 | switch address-space number |

| kernel thread switch | 6 | ||

| set caller id | 2 | save caller id for pct_ret | |

| find callee entry | 2 | pct entry address in callee | |

| close frame | 7 | 7 | |

| leave PAL mode | 2 | 2 | |

| total | 38 | 45 |

Table 6: PCT versus IPC; required cycles on Alpha 21164. For the PCT implementation we made the assumptions that (a) the entry address for the callee is maintained in some kernel control structure; (b) the callee must be able to specify a stack for the PCT call or – if the caller specifies it – the callee must be able to check it (the latter case requires the kernel to supply the callers identity); (c) stacking of return address and address space is needed. The cycles needed on user level to check the identity are left out of the comparison.

表6:PCT与IPC的比较;Alpha 21164上的所需周期。对于PCT的实现,我们做了如下假设:(a)被调用者的入口地址在一些内核控制结构中被维护;(b)被调用者必须能够为PCT调用指定一个堆栈,或者如果调用者指定堆栈,则被调用者必须能够检查堆栈(后一种情况需要内核提供调用者身份);(c)需要对返回地址和地址空间进行堆叠。在用户层面上检查身份所需的周期被排除在比较之外。

In addition, L4-style IPC provides message diversion (using Clans & Chiefs [20, 23]). A message crossing a clan border is redirected to the user-level chief of the clan who can inspect and handle the message. This can be used as a basis for the implementation of mandatory access control policies or isolation of suspicious objects. For security reasons, the redirection has to be enforced by the kernel. Clan-based redirection also enables distributed IPC through a user-level network server. Each machine is encapsulated by a clan so that inter-machine IPC is automatically redirected to the network server which forwards it through the network.

此外,L4 风格的 IPC 提供了消息分流(使部族和首领[20,23])。越过部族边界的消息会被重定向到该部族的用户级首领,他可以检查和处理该消息。这可以作为实施强制访问控制政策或隔离可疑对象的基础。出于安全考虑,重定向必须由内核来执行。基于部族的重定向还可以通过用户级网络服务器实现分布式 IPC。每台机器都被一个部族封装起来,这样机器间的 IPC 就会被自动重定向到网络服务器上,并通过网络转发。

Taking the additionally required user-level cycles into account, we currently see no performance benefit for PCT. However, a conceptual difference should be noted: A PCT takes the thread to another address space so that the set of active threads does not change. An IPC transfers a message from a sender thread to a destination thread; both threads remain in their respective address spaces but the set of active threads changes. Lazy scheduling techniques [21] remove the additional costs of the second model so that in most cases both are equivalent from a performance point of view.