Adam Belay, Andrea Bittau, Ali Mashtizadeh, David Terei, David Mazières, Christos Kozyrakis

Stanford University

摘要 Abstract

Dune is a system that provides applications with direct but safe access to hardware features such as ring protection, page tables, and tagged TLBs while preserving the existing OS interfaces for processes. Dune uses the virtualization hardware in modern processors to provide a process, rather than a machine abstraction. It consists of a small kernel module that initializes virtualization hardware and mediates interactions with the kernel, and a user-level library that helps applications manage privileged hardware features. We present the implementation of Dune for 64bit x86 Linux. We use Dune to implement three user-level applications that can benefit from access to privileged hardware: a sandbox for untrusted code, a privilege separation facility, and a garbage collector. The use of Dune greatly simplifies the implementation of these applications and provides significant performance advantages.

Dune 是一个系统,它为应用程序提供对硬件功能(如环保护、页表和标记 TLB)的直接但安全的访问,同时保留了现有的操作系统的进程接口。Dune 使用现代处理器中的虚拟化硬件来管理一个进程,而不是虚拟机。它由一个小型内核模块和一个用户级库组成,前者用于初始化虚拟化硬件并协调与内核的交互,后者用于帮助应用程序管理特权硬件功能。我们介绍了 64 位 x86 Linux 的 Dune 的实现。我们用 Dune 实现了三个用户级应用,它们可以从访问特权硬件中受益:一个用于不受信任的代码的沙盒、一个特权分离工具和垃圾收集器。Dune 的使用极大地简化了这些应用程序的实现,并提供了显著的性能优势。

1 介绍 Introduction

A wide variety of applications stand to benefit from access to “kernel-only” hardware features. As one example, Azul Systems demonstrates significant speedups in garbage collection through the use of paging hardware [15, 36]. As another example, process migration, though implementable within a user program, can benefit considerably from access to page faults [40] and system calls [32]. In some cases, it might even be appropriate to replace the kernel entirely to meet the needs of a particular application. For example, IBOS improves browser security by moving browser abstractions into the lowest OS layers [35].

各种各样的应用程序都可以从访问 “内核专用 “的硬件功能中受益。作为一个例子,Azul 系统公司通过使用分页硬件[15,36]展示了垃圾收集的显著加速。另一个例子是,进程迁移,虽然可以在用户程序中实现,但可以从访问页面错误[40]和系统调用[32]中大大受益。在某些情况下,甚至可以完全替换内核以满足特定应用程序的需要。例如,IBOS 通过将浏览器的抽象转移到最低的操作系统层来提高浏览器的安全性[35]。

Such systems require changes in the kernel because hardware access in userspace is restricted for security and isolation reasons. Unfortunately, modifying the kernel is not ideal in practice because kernel changes can be fairly intrusive and, if done incorrectly, affect whole system stability. Moreover, if multiple applications require kernel changes, there is no guarantee that the changes will compose.

这样的系统需要修改内核,因为出于安全和隔离的原因,用户态的硬件访问受到限制。不幸的是,修改内核在实践中并不理想,因为内核的改变可能是相当具有侵入性的,如果做得不对,会影响整个系统的稳定性。此外,如果有多个应用程序需要修改内核,则无法保证这些更改能够正确地组合到一起。

Another strategy is to bundle applications into virtual machine images with specialized kernels [4, 14]. Many modern CPUs contain virtualization hardware with which guest operating systems can safely and efficiently access kernel hardware features. Moreover, virtual machines provide failure containment similar to that of processes— i.e., buggy or malicious behavior should not bring down the entire physical machine.

另一种策略是将应用程序捆绑到具有专门内核的虚拟机镜像中[4,14]。许多现代的 CPU 包含虚拟化硬件,有了这些硬件,客户操作系统可以安全有效地访问内核的硬件功能。此外,虚拟机提供了类似于进程的错误控制,即错误或恶意行为不应使整个物理机停机。

Unfortunately, virtual machines offer poor integration with the host operating system. Processes expect to inherit file descriptors from their parents, spawn other processes, share a file system and devices with their parents and children, and use IPC services such as Unix-domain sockets. Moving a process to a virtual machine for, say, speeding up garbage collection is likely to break many assumptions and may simply not be worth the hassle. Moreover, producing a kernel for an application-specific virtual machine is no small task. Production kernels such as Linux are complex and hard to modify. Yet implementing a special-purpose kernel with a simple virtual memory layer is also challenging. In addition to virtual memory, one must support a file system, a networking stack, device drivers, and a bootstrap process.

不幸的是,虚拟机与主机操作系统的集成很差。进程期望从其父进程继承文件描述符,派生其他进程,与其父进程和子进程共享文件系统和设备,以及使用 IPC 服务(如 Unix 域套接字)。将进程移动到虚拟机(例如,加速垃圾收集)可能会打破许多假设,并且可能根本不值得这么麻烦。此外,为特定于应用程序的虚拟机制作内核是一项艰巨的任务。像 Linux 这样的生产型内核很复杂,很难修改。然而,实现具有简单虚拟内存层的专用内核也是具有挑战性的。除了虚拟内存之外,还必须支持文件系统、网络堆栈、设备驱动程序和引导进程。

This paper introduces a new approach to application use of kernel hardware features: using virtualization hardware to provide a process, rather than a machine abstraction. We have implemented this approach for Linux on 64-bit Intel CPUs in a system called Dune. Dune provides a loadable kernel module that works with unmodified Linux kernels. The module allows processes to enter “Dune mode,” an irreversible transition in which, through virtualization hardware, safe and fast access to privileged hardware features is enabled, including privilege modes, virtual memory registers, page tables, and interrupt, exception, and system call vectors. We provide a user-level library, libDune, to facilitate the use of these features.

本文介绍了一种应用程序使用内核硬件特性的新方法:使用虚拟化硬件来提供进程,而不是虚拟机。我们已经在一个名为 Dune 的系统中为 64 位 Intel CPU 上的 Linux 实现了这种方法。Dune 提供了一个可加载的内核模块,可以与未经修改的 Linux 内核一起使用。该模块允许进程进入"Dune 模式”,这是一种不可逆的转换,在这种转换中,通过虚拟化硬件,可以安全快速地访问特权硬件功能,包括特权模式、虚拟内存寄存器、页表以及中断、异常和系统调用向量。我们提供了一个用户级别的库 libDune,以方便使用这些功能。

For applications that fit its paradigm, Dune offers several advantages over virtual machines. First, a Dune process is a normal Linux process, the only difference being that it uses the VMCALL instruction to invoke system calls. This means that Dune processes have full access to the rest of the system and are an integral part of it, and that Dune applications are easy to develop (like application programming, not kernel programming). Second, because the Dune kernel module is not attempting to provide a machine abstraction, the module can be both simpler and faster. In particular, the virtualization hardware can be configured to avoid saving and restoring several pieces of hardware state that would be required for a virtual machine.

对于符合其范式的应用,Dune 提供了比虚拟机更多的优势。首先,Dune 进程是一个正常的 Linux 进程,唯一的区别是它使用 VMCALL 指令来调用系统调用。这意味着 Dune 进程可以完全访问系统的其他部分,是系统的一个组成部分,而且 Dune 应用程序很容易开发(类似于应用程序编程,而不是内核编程)。其次,由于 Dune 内核模块并不试图提供机器抽象,因此该模块可以更简单、更快速。特别是,可以对虚拟化硬件进行配置,以避免保存和恢复虚拟机所需的若干硬件状态。

With Dune we contribute the following:

通过 Dune,我们做出了以下贡献:

We present a design that uses hardware-assisted virtualization to safely and efficiently expose privileged hardware features to user programs while preserving standard OS abstractions.

我们提出了一种使用硬件辅助虚拟化的设计,以安全高效地向用户程序公开特权硬件功能,同时保留标准操作系统抽象。

We evaluate three hardware features in detail and show how they can benefit user programs: exceptions, paging, and privilege modes.

我们详细评估了三种硬件特性,并展示了它们如何使用户程序受益:异常、分页和特权模式。

We demonstrate the end-to-end utility of Dune by implementing and evaluating three use cases: sandboxing, privilege separation, and garbage collection.

我们通过实现和评估三个用例来证明 Dune 的端到端效用:沙盒、特权分离和垃圾收集。

2 虚拟化和硬件 Virtualization and Hardware

In this section, we review the hardware support for virtualization and discuss which privileged hardware features Dune can expose. Throughout the paper, we describe Dune in terms of x86 CPUs and Intel VT-x. However, this is not fundamental to our design, and in Section 7, we broaden our discussion to include other architectures that could be supported in the future.

在本节中,我们将回顾虚拟化的硬件支持,并讨论 Dune 可以公开哪些特权硬件功能。在整篇文章中,我们用 x86 CPU 和 Intel VT-x 来描述 Dune。然而,这并不是我们设计的基础,在第 7 节中,我们将我们的讨论扩展到包括将来可能支持的其他架构。

2.1 英特尔 VT-x 扩展 The Intel VT-x Extension

To improve virtualization performance and simplify VMM implementation, Intel has developed VT-x [37], a virtualization extension to the x86 ISA. AMD also provides a similar extension with a different hardware interface called SVM [3].

为了提高虚拟化性能并简化 VMM 实现,英特尔开发了 VT-x[37],这是 x86 ISA 的虚拟化扩展。AMD 也提供了一个类似的扩展,带有一个不同的硬件接口,称为 SVM[3]。

The simplest method of adapting hardware to support virtualization is to introduce a mechanism for trapping each instruction that accesses a privileged state so that emulation can be performed by a VMM. VT-x embraces a more sophisticated approach, inspired by IBM’s interpretive execution architecture [31], whereas many instructions as possible, including most that access privileged state, are executed directly in hardware without any intervention from the VMM. This is possible because hardware maintains a “shadow copy” of the privileged state. The motivation for this approach is to increase performance, as traps can be a significant source of overhead.

调整硬件以支持虚拟化的最简单方法是引入一种机制,用于捕获访问特权状态的每个指令,以便由 VMM 来进行仿真。受 IBM 的解释执行架构[31]的启发,VT-x 采用了一种更复杂的方法,使尽可能多的指令(包括大多数访问特权状态的指令)直接在硬件中执行,而不需要 VMM 的任何干预。这是可能的,因为硬件维护特权状态的"影子副本”。这种方法的动机是提高性能,因为陷阱可能是开销的重要来源。

VT-x adopts a design where the CPU is split into two operating modes: VMX root and VMX non-root mode. VMX root mode is generally used to run the VMM and does not change CPU behavior, except to enable access to new instructions for managing VT-x. VMX non-root mode, on the other hand, restricts CPU behavior and is intended for running virtualized guest OSes.

VT-x 采用了一种设计,将 CPU 分成两种操作模式。VMX root 模式和 VMX 非 root 模式。VMX root 模式通常用于运行 VMM,除了能够访问用于管理 VT-x 的新指令外,不会改变 CPU 的行为。另一方面,VMX 非 root 模式限制了 CPU 行为,用于运行虚拟化的客户操作系统。

Transitions between VMX modes are managed by hardware. When the VMM executes the VMLAUNCH or VMRESUME instruction, the hardware performs a VM entry; placing the CPU in VMX non-root mode and executing the guest. Then, when action is required from the VMM, the hardware performs a VM exit, placing the CPU back in VMX root mode and jumping to a VMM entry point. Hardware automatically saves and restores most architectural states during both types of transitions. This is accomplished by using buffers in a memory-resident data structure called the VM control structure (VMCS).

VMX 模式之间的转换由硬件管理。当 VMM 执行 VMLAUNCH 或 VMRESUME 指令时,硬件会执行 VM 入口;将 CPU 置于 VMX 非 root 模式并执行客户操作系统。然后,当需要来自 VMM 的操作时,硬件执行 VM 退出,将 CPU 放回 VMX root 模式并跳转到 VMM 入口点。在这两种类型的转换过程中,硬件会自动保存和恢复大多数架构状态。这是通过使用称为 VM 控制结构(VMCS)的内存驻留数据结构中的缓冲区来实现的。

In addition to storing architectural states, the VMCS contains a myriad of configuration parameters that allow the VMM to control execution and specify which type of events should generate VM exits. This gives the VMM considerable flexibility in determining which hardware is exposed to the guest. For example, a VMM could configure the VMCS so that the HLT instruction causes a VM exit or it could allow the guest to halt the CPU. However, some hardware interfaces, such as the interrupt descriptor table (IDT) and privilege modes, are exposed implicitly in VMX non-root mode and never generate VM exits when accessed. Moreover, a guest can manually request a VM exit by using the VMCALL instruction.

除了存储架构状态外,VMCS 还包含大量的配置参数,允许 VMM 控制执行,并指定哪种类型的事件应产生 VM 退出。这使 VMM 在确定哪些硬件公开给客户时有相当大的灵活性。例如,VMM 可以配置 VMCS,使 HLT 指令导致虚拟机退出,或者允许客户停止 CPU。然而,一些硬件接口,如中断描述符表(IDT)和特权模式,在 VMX 非 root 模式下是隐式公开的,在访问时不会产生 VM 退出。此外,客户可以通过使用 VMCALL 指令手动请求 VM 退出。

Virtual memory is perhaps the most difficult hardware feature for a VMM to expose safely. A straw man solution would be to configure the VMCS so that the guest has access to the page table root register, %CR3. However, this would place complete trust in the guest because it would be possible for it to configure the page table to access any physical memory address, including memory that belongs to the VMM. Fortunately, VT-x includes a dedicated hardware mechanism, called the extended page table (EPT), that can enforce memory isolation on guests with direct access to virtual memory. It works by applying a second, underlying, layer of address translation that can only be configured by the VMM. AMD’s SVM includes a similar mechanism to the EPT, referred to as a nested page table (NPT).

虚拟内存可能是 VMM 最难安全公开的硬件特性。一个棘手的解决方案是配置 VMCS,使客户可以访问页表根寄存器%CR3。然而,这将完全信任客户,因为它有可能配置页表以访问任何物理内存地址,包括属于 VMM 的内存。幸运的是,VT-x 包括一个专门的硬件机制,称为扩展页表(EPT),可以在直接访问虚拟内存的客户身上强制执行内存隔离。它通过应用只能由 VMM 配置的第二个底层地址转换层来工作。AMD 的 SVM 包括一个类似于 EPT 的机制,被称为嵌套页表(NPT)。

2.2 支持的硬件特性 Supported Hardware Features

| Mechanism | Priviledged Instructions |

|---|---|

| Exceptions | LIDT, LTR, IRET, STI, CLI |

| Virtual Memory | MOV CRn, INVLPG, INVPCID |

| Privilege Modes | SYSRET, SYSEXIT, IRET |

| Segmentation | LGDT, LLDT |

Table 1: Hardware features exposed by Dune and their corresponding privileged x86 instructions.

表 1:Dune 公开的硬件特性及其相应的特权 x86 指令。

Dune uses VT-x to provide user programs with full access to x86 protection hardware. This includes three privileged hardware features: exceptions, virtual memory, and privilege modes. Table 1 shows the corresponding privileged instructions made available for each feature. Dune also exposes segmentation, but we do not discuss it further, as it is primarily a legacy mechanism on modern x86 CPUs.

Dune 使用 VT-x 为用户程序提供对 x86 保护硬件的完全访问。这包括三个特权硬件功能:异常、虚拟内存和特权模式。表 1 显示了可用于每个功能的相应特权指令。Dune 还公开了分段,但我们不进一步讨论它,因为它主要是现代 x86 CPU 上的遗留机制。

Efficient support for exceptions is important in a variety of use cases such as emulation, debugging, and performance tracing. Normally, reporting an exception to a user program requires privilege mode transitions and an upcall mechanism (e.g., signals). Dune can reduce exception overhead because it uses VT-x to deliver exceptions directly in hardware. This does not, however, allow a Dune process to monopolize the CPU, as timer interrupts and other exceptions intended for the kernel will still cause a VM exit. The net result is that software overhead is eliminated and exception performance is determined by hardware efficiency alone. As just one example, Dune improves the speed of delivering page fault exceptions, when compared to SIGSEGV in Linux, by more than 4×. Several other types of exceptions are also accelerated, including breakpoints, floating-point overflow and underflow, divide by zero, and invalid opcodes.

在仿真、调试和性能跟踪等各种用例中,对异常的有效支持非常重要。通常,向用户程序报告异常需要特权模式转换和向上调用机制(例如,信号)。Dune 可以减少异常开销,因为它使用 VT-x 直接在硬件中传递异常。但是,这并不允许 Dune 进程独占 CPU,因为定时器中断和其他针对内核的异常仍然会导致 VM 退出。最终结果是消除了软件开销,并且异常性能仅由硬件效率决定。仅举一个例子,与 Linux 中的 SIGSEGV 相比,Dune 将传递页面错误异常的速度提高了 4 倍以上。其他几种类型的异常也得到了加速,包括断点、浮点上溢和下溢、被零除和无效操作码。

User programs can also benefit from fast and flexible access to virtual memory [5]. Use cases include checkpointing, garbage collection (evaluated in this paper), data-compression paging, and distributed shared memory. Dune improves virtual memory access by exposing page table entries to user programs directly, allowing them to control address translations, access permissions, global bits, and modified/accessed bits with simple memory references. In contrast, even the most efficient OS interfaces [17] add extra latency by requiring system calls to perform these operations. Letting applications write their page tables does not affect security because the underlying EPT exposes only the normal process address space, which is equally accessible without Dune.

用户程序也可以从快速灵活地访问虚拟内存中受益[5]。用例包括检查点、垃圾收集(本文对其进行了评估)、数据压缩分页和分布式共享内存。Dune 通过直接向用户程序公开页表条目来改善虚拟内存访问,允许用户程序通过简单的内存引用来控制地址转换、访问权限、全局位和修改/访问位。相反,即使是最高效的操作系统接口[17]也需要系统调用来执行这些操作,从而增加了额外的延迟。让应用程序写入它们的页表不会影响安全性,因为底层的 EPT 只公开正常的进程地址空间,在没有 Dune 的情况下,同样可以访问。

Dune also gives user programs the ability to manually control TLB invalidations. As a result, page table updates can be performed in batches when permitted by the application. This is considerably more challenging to support in the kernel because it is difficult to defer TLB invalidations when general correctness must be maintained. In addition, Dune exposes TLB tagging by providing access to Intel’s recently added process-context identifier (PCID) feature. This permits a single-user program to switch between multiple page tables efficiently. Altogether, we show that using Dune results in a 7× speedup over Linux in the Appel and Li user-level virtual memory benchmarks [5]. This figure includes the use of exception hardware to reduce page fault latency.

Dune 还为用户程序提供了手动控制 TLB 无效的能力。因此,当应用程序允许时,可以批量执行页表更新。在内核中支持这一点更具挑战性,因为在必须保持一般正确性的情况下,很难推迟 TLB 的无效性。此外,Dune 通过提供对英特尔最近添加的进程上下文标识符(PCID)功能的访问来公开 TLB 标记。这允许单用户程序有效地在多个页表之间切换。总之,我们证明了在 Appel 和 Li 用户级虚拟内存基准测试[5]中,使用 Dune 可以比 Linux 加速 7 倍。这个数字包括使用异常硬件来减少页面错误延迟。

Finally, Dune exposes access to privilege modes. On x86, the most important privilege modes are ring 0 (supervisor mode) and ring 3 (user mode), although rings 1 and 2 are also available. Two motivating use cases for privilege modes are privilege separation and sandboxing of untrusted code, both evaluated in this paper. Dune can support privilege modes efficiently because VMX non-root mode maintains its own set of privilege rings. Hence, Dune allows hardware-enforced protection within a process in exactly the way kernels protect themselves from user processes. The supervisor bit in the page table is available to control memory isolation. Moreover, system call instructions trap the process itself, rather than the kernel, which can be used for system call interposition and to prevent untrusted code from directly accessing the kernel. Compared to ptrace in Linux, we show that Dune can intercept a system call with 25× less overhead.

最后,Dune 公开了对特权模式的访问。在 x86 上,最重要的特权模式是环 0(管理员模式)和环 3(用户模式),但环 1 和环 2 也可用。特权模式的两个激励性用例是特权分离和不可信代码的沙盒,本文对这两个用例进行了评估。Dune 可以有效地支持特权模式,因为 VMX 非 root 模式维护其自己的特权环。因此,Dune 允许在进程中进行硬件强制保护,就像内核保护自己不受用户进程的影响一样。页表中的特权位可用于控制内存隔离。此外,系统调用指令可以捕获进程本身,而不是内核,这可以用来进行系统调用干预,防止不受信任的代码直接访问内核。我们证明了,与 Linux 中的 ptrace 相比,Dune 可以以少 25 倍的开销拦截系统调用。

Although the hardware features Dune exposes suffice in supporting our motivating use cases, several other hardware features, such as cache control, debug registers, and access to DMA-capable devices could also be safely exposed through virtualization hardware. We leave these for future work and discuss their potential in Section 7.

尽管 Dune 公开的硬件功能足以支持我们的激励性用例,但其他几个硬件功能(如缓存控制、调试寄存器和对支持 DMA 的设备的访问)也可以通过虚拟化硬件安全地公开。我们把这些留给未来的工作,并在第 7 节中讨论它们的潜力。

3 内核对 Dune 的支持 Kernel Support for Dune

The core of Dune is a kernel module that manages VT-x and provides user programs with greater access to privileged hardware features. We describe this module here, including a system overview, a threat model, and a comparison to an ordinary VMM. We then explore three key aspects of the module’s operation: managing memory, exposing access to privileged hardware, and preserving access to kernel interfaces. Finally, we describe the Dune module we implemented for the Linux kernel.

Dune 的核心是一个管理 VT-x 的内核模块,并为用户程序提供对特权硬件功能的更大访问权限。我们在这里描述这个模块,包括系统概览、威胁模型以及与普通 VMM 的比较。然后,我们探讨了该模块运行的三个关键方面:管理内存,公开对特权硬件的访问,以及保留对内核接口的访问。最后,我们描述了我们为 Linux 内核实现的 Dune 模块。

3.1 系统概览 System Overview

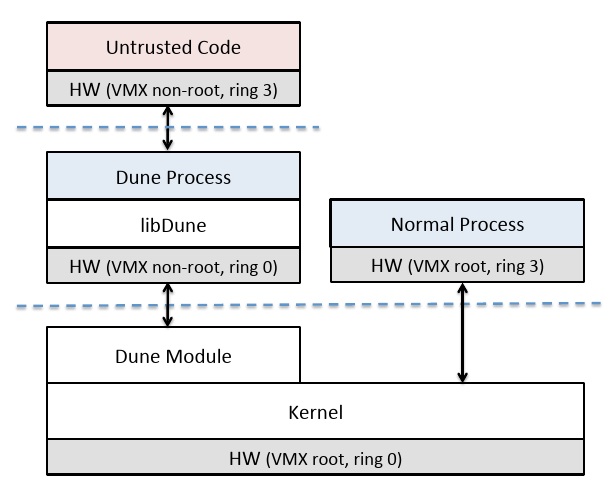

Figure 1: The Dune system architecture.

图 1: Dune 系统结构

Figure 1 shows a high-level view of the Dune architecture. Dune extends the kernel with a module that enables VT-x, placing the kernel in VMX root mode. Processes using Dune are granted direct but safe access to privileged hardware by running in VMX non-root mode. The Dune module intercepts VM exits, the only means for a Dune process to access the kernel, and performs any necessary actions such as servicing a page fault, calling a system call, or yielding the CPU after an HLT instruction. Dune also includes a library, called libDune, to assist with managing privileged hardware features in userspace, discussed further in Section 4.

图 1 显示了 Dune 架构的概览。Dune 使用启用 VT-x 的模块扩展内核,将内核置于 VMX root 模式。通过在 VMX 非 root 模式下运行,使用 Dune 的进程被授予对特权硬件的直接但安全的访问权限。Dune 模块拦截 VM 退出,这是 Dune 进程访问内核的唯一方式,并执行任何必要的操作,例如服务页面错误、调用系统调用或在 HLT 指令后放弃 CPU。Dune 还包括一个名为 libDune 的库,用于帮助管理用户空间中的特权硬件功能,将在第 4 节中进一步讨论。

We apply Dune selectively to processes that need it; processes that do not use Dune are completely unaffected. A process can enable Dune at any point by initiating a transition through an ioctl on the /dev/dune device, but once in Dune mode, a process cannot exit Dune mode. Whenever a Dune process forks, the child process does not start in Dune mode but can re-enter Dune if the use case requires it.

我们有选择地将 Dune 应用于需要它的进程;不使用 Dune 的进程则完全不受影响。一个进程可以在任何时候通过/dev/dune 设备上的 ioctl 启动转换来启用 Dune,但是一旦进入 Dune 模式,进程就无法退出 Dune 模式。每当一个 Dune 进程 fork 时,子进程不会在 Dune 模式下启动,但如果用例需要,可以重新进入 Dune。

The Dune module requires VT-x. As a result, it cannot be used inside a VM unless there is support for nested VT-x [6]; the performance characteristics of such a configuration are an interesting topic of future consideration. On the other hand, it is possible to run a VMM on the same machine as the Dune module, even if the VMM requires VT-x because VT-x can be controlled independently on each core.

Dune 模块需要 VT-x。因此,除非支持嵌套 VT-x[6],否则不能在 VM 中使用它。这种配置的性能特征是未来考虑的一个有趣的话题。另一方面,即使 VMM 需要 VT-x,也可以在与 Dune 模块相同的机器上运行 VMM,因为 VT-x 可以在每个核心上独立控制。

3.2 威胁模型 Threat Model

Dune exposes privileged CPU features without affecting the existing security model of the underlying OS. Any external effects produced by a Dune-enabled process could be produced without Dune through the same series of system calls. However, by exposing hardware privilege modes, Dune enables additional privilege-separation techniques within a process that would not otherwise be practical.

Dune 在不影响底层操作系统的现有安全模型的情况下公开特权 CPU 功能。由启用 Dune 的进程产生的任何外部效果都可以通过相同的一系列系统调用在没有 Dune 的情况下产生。然而,通过公开硬件特权模式,Dune 在进程中启用了额外的特权分离技术,而这些技术在其他情况下并不实用。

We assume that the CPU is free of defects, although we acknowledge that in rare cases exploitable hardware flaws have been identified [26, 27].

我们假设 CPU 没有缺陷,尽管我们承认在极少数情况下已经发现了可利用的硬件缺陷[26,27]。

3.3 与 VMM 的对比 Comparing to a VMM

Though all software using VT-x shares a common structure, Dune’s use of VT-x deviates from that of standard VMMs. Specifically, Dune exposes a process environment instead of a machine environment. As a result, Dune is not capable of supporting a normal guest OS, but this permits Dune to be lighter weight and more flexible. Some of the most significant differences are as follows:

尽管所有使用 VT-x 的软件都有一个共同的结构,但 Dune 对 VT-x 的使用与标准 VMM 的使用不同。具体来说,Dune 公开了一个进程环境,而不是机器环境。因此,Dune 不能支持普通的客户操作系统,但这使得 Dune 更轻量,更灵活。一些最显著的差异如下:

Hypercalls are a common way for VMMs to support paravirtualization, a technique in which the guest OS is modified to use interfaces that are more efficient and less difficult to virtualize. In Dune, by contrast, the hypercall mechanism invokes normal Linux system calls. For example, a VMM might provide a hypercall to register an interrupt handler for a virtual network device, whereas a Dune process would use a hypercall to call read on a TCP socket.

超调用是 VMM 支持半虚拟化的一种常见方式,在这种技术中,客户操作系统被修改为使用更有效、更不容易虚拟化的接口。相比之下,在 Dune 中,超调用机制调用了正常的 Linux 系统调用。例如,VMM 可能会提供一个超调用来注册一个虚拟网络设备的中断处理程序,而 Dune 进程会使用一个超调用来调用 TCP 套接字上的 read。

Many VMMs emulate physical hardware interfaces to support unmodified guest OSes. In Dune, only hardware features that can be directly accessed without VMM intervention are made available; in cases where this is not possible, a Dune process falls back on the OS. For example, most VMMs go to great lengths to present a virtual graphics card interface to support a frame buffer. By contrast, Dune processes employ the normal OS display service, usually, an X server accessed over a Unix-domain socket and shared memory.

许多 VMM 模拟了物理硬件接口,以支持未经修改的客户操作系统。在 Dune 中,只有那些不需要 VMM 干预就能直接访问的硬件功能才是可用的;在无法做到这一点的情况下,Dune 进程会回到操作系统上。例如,大多数 VMM 不遗余力地提出一个虚拟图形卡接口来支持帧缓冲器。相比之下,Dune 进程采用正常的操作系统显示服务,通常是通过 Unix 域套接字和共享内存访问 X 服务器。

A typical VMM must save and restore all state that is necessary to support a guest OS. In Dune, we can limit the differences in guest and host states because processes using Dune have a narrower hardware interface. This results in reductions in the overhead of performing VM entries and VM exits.

一个典型的 VMM 必须保存和恢复所有的状态,这是支持客户操作系统所必需的。在 Dune 中,我们可以限制客户和主机状态的差异,因为使用 Dune 的进程具有较窄的硬件接口。这导致执行 VM 进入和 VM 退出的开销减少。

VMMs place each VM in a separate address space that emulates flat physical memory. In Dune, we configure the EPT to reflect process address spaces. As a result, the memory layout can be sparse and memory can be coherently shared when two processes map the same memory segment.

VMM 将每个虚拟机放在一个单独的地址空间中,模拟物理内存。在 Dune 中,我们配置 EPT 以反映进程地址空间。结果,当两个进程映射相同的内存段时,内存布局可以是稀疏的,并且内存可以被一致地共享。

Despite these differences, the Dune module could be considered a type-2 hypervisor [22] because it runs on top of an existing OS kernel.

尽管有这些差异,Dune 模块可以被认为是一个第二类管理程序[22],因为它运行在现有的操作系统内核之上。

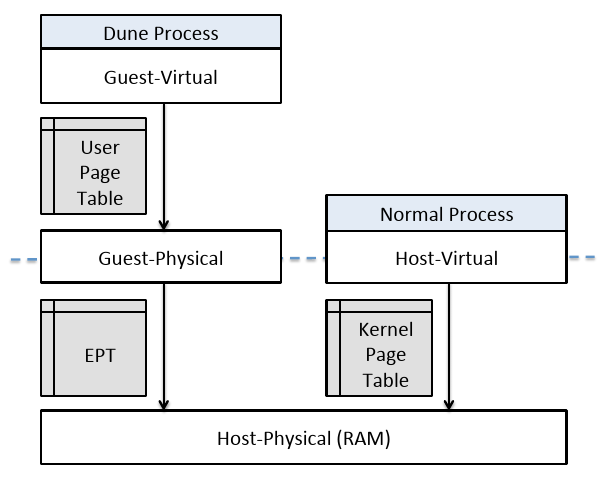

Figure 2: Virtual memory in Dune.

图 2: Dune 中的虚拟内存

3.4 内存管理 Memory Management

Memory management is one of the biggest responsibilities of the Dune module. The challenge is to expose direct page table access to user programs while preventing arbitrary access to physical memory. Moreover, our goal is to provide a normal process memory address space by default, permitting user programs to add just the functionality they need instead of completely replacing kernel-level memory management.

内存管理是 Dune 模块的最大责任之一。我们面临的挑战是如何向用户程序提供直接的页表访问,同时防止对物理内存的任意访问。此外,我们的目标是默认提供一个正常的进程内存地址空间,允许用户程序只添加他们需要的功能,而不是完全取代内核级内存管理。

Paging translations occur in three separate cases in Dune, shown in Figure 2. One translation is specified by the kernel’s standard page table. In virtualization terminology, this is the host-virtual to host-physical (i.e., raw memory) translation. Host-virtual addresses are ordinary virtual addresses, but they are only used by the kernel and normal processes. For processes using Dune, a user-controlled page table maps guest-virtual addresses to guest-physical. Then the EPT, managed by the kernel, performs an additional translation from guest-physical to host-physical. All memory references made by processes using Dune can only be guest-virtual, allowing for isolation and correctness to be enforced in the EPT while application-specific functionality and optimizations can be applied in the user page table.

在 Dune 中,分页转换发生在三种不同的情况下,如图 2 所示。一个转换由内核的标准页表指定。在虚拟化术语中,这是主机-虚拟到主机-物理(即原始内存)的转换。主机虚拟地址是普通的虚拟地址,但仅供内核和正常进程使用。对于使用 Dune 的进程,用户控制的页表将客户虚拟地址映射到客户物理地址。然后,由内核管理的 EPT 执行从客户物理到主机物理的附加转换。使用 Dune 的进程所做的所有内存引用只能是客户虚拟的,从而允许在 EPT 中实施隔离和正确性,同时可以在用户页表中应用特定于应用程序的功能和优化。

Ideally, we would like to match the EPT to the kernel’s page table as closely as possible because of our goal to give processes using Dune access to the same address space they would have as normal processes. If it were permitted by hardware, we would simply point the EPT and the kernel’s page table to the same page root. Unfortunately, two limitations make this impossible. First, the EPT requires a different binary format from the standard x86 page table. Second, Intel x86 processors limit the address width of guest-physical addresses to be the same as host-physical addresses. In a standard virtual machine environment, this would not be a concern because any machine being emulated would have a realistically bounded amount of RAM. For Dune, however, the problem is that we want to expose the full host-virtual address space and yet the guest-physical address space is limited to a smaller size (e.g., a 36-bit physical limit vs. a 48-bit virtual limit on many contemporary Intel processors). We note that this issue is not present when running in 32-bit protected mode, as physical addresses are at least as large as virtual addresses.

理想情况下,我们希望将 EPT 与内核的页表尽可能紧密地匹配,因为我们的目标是让使用 Dune 访问的进程拥有与正常进程相同的地址空间。如果硬件允许,我们可以简单地将 EPT 和内核的页表指向相同的页根。不幸的是,有两个限制使这不可能。首先,EPT 需要与标准 x86 页表不同的二进制格式。其次,Intel x86 处理器将客户物理地址的地址宽度限制为与主机物理地址相同。在标准的虚拟机环境中,这不是一个问题,因为任何被模拟的机器都具有实际有限的内存。然而,对于 Dune,问题在于我们想要公开完整的主机虚拟地址空间,而客户物理地址空间却被限制为较小的大小(例如,在许多当代 Intel 处理器上的 36 位物理限制与 48 位虚拟限制)。我们注意到,在 32 位保护模式下运行时不存在此问题,因为物理地址至少与虚拟地址一样大。

Our solution to EPT format incompatibility is to query the kernel for process memory mappings and to manually update the EPT to reflect them. We start with an empty EPT. Then, we receive an EPT fault (a type of VM exit) each time a missing EPT entry is accessed. The fault handler crafts a new EPT entry that reflects an address translation and permission reported by the kernel’s page fault handler. Occasionally, address ranges will need to be unmapped. In addition, the kernel requires the page to access information, to assist with swapping, and page dirty status, to determine when write-back to disk is necessary. Dune supports all of these cases by hooking into an MMU notifier chain, the same approach used by KVM [30]. For example, when an address is unmapped, the Dune module receives an event. It then evicts affected EPT entries and sets dirty bits in the appropriate Linux page structures.

我们对 EPT 格式不兼容的解决方案是在内核中查询进程内存映射,并手动更新 EPT 以反映它们。我们从空的 EPT 开始。然后,每次访问缺失的 EPT 条目时,我们都会收到 EPT 错误(一种类型的 VM 退出)。错误处理程序创建新的 EPT 条目,该条目反映由内核的页面错误处理程序报告的地址转换和权限。有时,需要取消地址范围的映射。此外,内核需要页面来访问信息,以帮助交换和页面脏状态,以确定何时需要写回磁盘。Dune 通过挂接到 MMU 通知器链来支持所有这些情况,KVM[30]使用了相同的方法。例如,当地址被取消映射时,Dune 模块接收事件。然后,它会逐出受影响的 EPT 条目,并在相应的 Linux 页面结构中设置脏位。

We work around the address width issue by allowing only some address ranges to be mapped in the EPT. Specifically, we only permit addresses from the beginning of the process (i.e., the heap, code, and data segments), the mmap region, and the stack. Currently, we limit each of these regions to 4GB, allowing us to compress the address space to fit in the first 12GB of the EPT. Typically the user’s page table will then expand the addresses to their original layout. This could result in incompatibilities in programs that use nonstandard portions of the address space, though such cases are rare. A more sophisticated solution might pack each virtual memory area into the guest-physical address space in arbitrary order and then provide the user program the additional information required to remap the segment to the correct guest-virtual address in its page table, thus avoiding the possibility of unaddressable memory regions.

我们通过只允许在 EPT 中映射某些地址范围来解决地址宽度问题。具体来说,我们只允许进程开头(即堆、代码和数据段)、mmap 区域和堆栈中的地址。目前,我们将这些区域中的每一个限制为 4GB,允许我们压缩地址空间以适应 EPT 的前 12GB。通常,用户的页表随后会将地址扩展到其原始布局。这可能会导致使用非标准地址空间部分的程序出现不兼容的情况,尽管这种情况很少发生。更复杂的解决方案可能以任意顺序将每个虚拟内存区打包到客户物理地址空间中,然后向用户程序提供将段重新映射到其页表中的正确客户虚拟地址所需的附加信息,从而避免不可寻址内存区的可能性。

3.5 将访问公开给硬件 Exposing Access to Hardware

As discussed previously, Dune exposes access to exceptions, virtual memory, and privilege modes. Exceptions and privilege modes are implicitly available in VMX non-root mode and do not require any special configuration. On the other hand, virtual memory requires access to the %CR3 register, which can be granted in the VMCS. We maintain a separate VMCS for each process to allow for per-process configuration of privileged state and to support context switching more easily and efficiently.

如前所述,Dune 公开了对异常、虚拟内存和特权模式的访问。异常和特权模式在 VMX 非 root 模式中是隐式可用的,并且不需要任何特殊配置。另一方面,虚拟内存需要访问%CR3 寄存器,这可以在 VMCS 中授权。我们为每个进程维护单独的 VMCS,以允许每个进程配置特权状态,并更容易和有效地支持上下文切换。

x86 includes a variety of control registers that determine which hardware features are enabled (e.g., floating-point, SSE, no execute, etc.) Although we could have permitted Dune processes to configure these directly, we instead mirror the configuration set by the kernel. This allows us to support a normal process environment; permitting many configuration changes would break compatibility with user programs. For example, it makes little sense for a 64-bit process to disable long mode. There are, however, a couple of important exceptions to this rule. First, we allow user programs to disable paging because it is the only method available on x86 to clear global TLB entries. Second, we give user programs some control over floating-point hardware to allow for the support of lazy floating point state management.

x86 包括各种控制寄存器,决定启用哪些硬件功能(如浮点、SSE、不执行等)。虽然我们可以允许 Dune 进程直接配置这些功能,但我们却反映了内核设置的配置。这使我们能够支持一个正常的进程环境;允许许多配置更改会破坏与用户程序的兼容性。例如,对于一个 64 位进程来说,禁用长模式是没有意义的。然而,这个规则有几个重要的例外。首先,我们允许用户程序禁用分页,因为它是 x86 上唯一可以用来清除全局 TLB 项的方法。第二,我们给用户程序一些对浮点硬件的控制权,以支持惰性浮点状态管理。

In some cases, Dune restricts access to hardware registers for performance reasons. For instance, Dune does not allow modification to MSRs to avoid the relatively high overhead of saving and restoring them during each system call. The FS and GS base registers are exceptions because they are not only used frequently but are also saved and restored by hardware automatically. MSR LSTAR, which contains the address of the system call handler, is a special case where Dune allows read-only access. This allows a user process to map code for a system call handler at the existing address (by manipulating its page table) instead of changing the register to a new address and, as a result, harming performance.

在某些情况下,Dune 出于性能考虑,限制了对硬件寄存器的访问。例如,Dune 不允许修改 MSR,以避免在每次系统调用中保存和恢复 MSR 的相对高的开销。FS 和 GS 基址寄存器是个例外,因为它们不仅被频繁使用,而且还被硬件自动保存和恢复。MSR LSTAR,包含系统调用处理程序的地址,是 Dune 允许只读访问的一个特殊情况。这允许用户进程将系统调用处理程序的代码映射到现有地址(通过操作其页表),而不是将寄存器更改为新地址,从而损害性能。

Dune exposes raw access to the time stamp counter (TSC). By contrast, most VMMs virtualize the TSC to avoid confusing guest kernels, which tend to make timing assumptions that could be violated if time spent in the VMM is made visible.

Dune 公开了对时间戳计数器(TSC)的原始访问。相比之下,大多数 VMM 将 TSC 虚拟化,以避免混淆客户内核,因为客户内核倾向于做出计时假设,如果在 VMM 中花费的时间是可见的,那么这些假设就可能被违反。

3.6 保留操作系统接口 Preserving OS Interfaces

In addition to exposing privileged hardware features, Dune preserves access to OS system calls. Normal system call invocation instructions will only trap within the process itself and do not cause a VM exit. Instead, processes must use VMCALL, the hypercall instruction, to make system calls. The Dune module vectors hypercalls through the kernel’s system call table. In some cases, it must perform extra actions before calling the system call handler. For example, during an exit system call, Dune performs cleanup tasks.

除了公开特权硬件功能外,Dune 还保留了对操作系统系统调用的访问。正常的系统调用指令只会在进程本身内部产生陷阱,不会导致虚拟机退出。相反,进程必须使用 VMCALL,即超调用指令,来进行系统调用。Dune 模块通过内核的系统调用表引导虚拟化调用。在某些情况下,它必须在调用系统调用处理程序之前执行额外的操作。例如,在 exit 系统调用时,Dune 会执行清理任务。

Dune completely changes how signal handlers are invoked. Some signals are obviated by more efficient direct hardware support. For example, hardware page faults largely subsume the role of SIGSEGV. For other signals (e.g., SIGINT), the Dune module injects fake hardware interrupts into the process. This is not only an efficient mechanism but also has the advantage of correctly composing with privilege modes. For example, if a user process were running in ring 3 to sandbox untrusted code, the hardware would automatically transition it to ring 0 to service the signal securely.

Dune 完全改变了信号处理程序的调用方式。一些信号被更有效的直接硬件支持所取代。例如,硬件页面错误在很大程度上取代了 SIGSEGV 的作用。对于其他信号(例如,SIGINT),Dune 模块将假的硬件中断注入进程中。这不仅是一种有效的机制,而且还具有与特权模式正确组合的优势。例如,如果一个用户进程运行在第 3 环,以沙盒不受信任的代码,硬件将自动过渡到第 0 环,以安全地提供信号。

3.7 实现 Implementation

Dune presently supports Linux running on Intel x86 processors in 64-bit long mode. Support for AMD CPUs and 32-bit mode is possible future additions. To keep changes to the kernel as unintrusive as possible, we developed Dune as a dynamically loadable kernel module. Our implementation is based partially on KVM [30]. Specifically, it shares code for managing low-level VT-x operations. However, high-level code is not shared with KVM because Dune operates differently from a VMM. Furthermore, our Dune module is simpler than KVM, consisting of only 2,509 lines of code.

Dune 目前支持以 64 位长模式在 Intel x86 处理器上运行的 Linux。未来可能会增加对 AMD CPU 和 32 位模式的支持。为了使内核的更改尽可能不受干扰,我们将 Dune 开发为可动态加载的内核模块。我们的实现部分基于 KVM[30]。具体来说,它共享用于管理低级 VT-x 操作的代码。但是,高级代码不与 KVM 共享,因为 Dune 的操作方式与 VMM 不同。此外,我们的 Dune 模块比 KVM 更简单,只包含 2509 行代码。

In Linux, user threads are supported by the kernel, making them nearly identical to processes except they have a shared address space. As a result, it was easiest for us to create a VMCS for each thread instead of merely each process. One interesting consequence is that it is possible for both threads using Dune and threads not using Dune to belong to the same process.

在 Linux 中,内核支持用户线程,这使得用户线程与进程几乎相同,只是它们具有共享地址空间。因此,为每个线程而不是仅仅为每个进程创建 VMCS 对我们来说是最容易的。一个有趣的结果是,使用 Dune 的线程和不使用 Dune 的线程可能属于同一个进程。

Our implementation is capable of supporting thousands of processes at a time. The reason is that processes using Dune are substantially lighter-weight than full virtual machines. Efficiency is further improved by using virtual processor identifiers (VPIDs). VPIDs enable a unique TLB tag to be assigned to each Dune process, and, as a result, hypercalls and context switches do not require TLB invalidations.

我们的实现能够同时支持成千上万的进程。原因是,使用 Dune 的进程比完整的虚拟机要轻得多。通过使用虚拟处理器标识符(VPID),效率得到进一步提高。VPID 能够为每个 Dune 进程分配一个独特的 TLB 标签,因此,超调用和上下文切换不需要使 TLB 失效。

One limitation in our implementation is that we cannot efficiently detect when EPT pages have been modified or accessed, which is needed for swapping. Intel recently added hardware support for this capability, so it should be easy to rectify this limitation. For now, we take a conservative approach and always report pages as modified and accessed during MMU notifications to ensure correctness.

我们的实现中的一个限制是,我们不能有效地检测 EPT 页面何时被修改或访问,而这是交换所需要的。英特尔最近添加了对此功能的硬件支持,因此应该很容易纠正此限制。目前,我们采取保守的方法,并始终在 MMU 通知期间报告修改和访问的页面,以确保正确性。

4 用户态环境 User-mode Environment

The execution environment of a process using Dune has some differences from a normal process. Because privilege rings are an exposed hardware feature, one difference is that user code runs in ring 0. Despite changing the behavior of certain instructions, this does not typically result in any incompatibilities for existing code. Ring 3 is also available and can optionally be used to confine untrusted code. Another difference is that system calls must be performed as hypercalls. To simplify supporting this change, we provide a mechanism that can detect when a system call is performed from ring 0 and automatically redirect it to the kernel as a hypercall. This is one of many features included in libDune.

使用 Dune 的进程的执行环境与普通进程有一些不同。由于特权环是一种公开的硬件功能,因此一个不同之处是用户代码在环 0 中运行。尽管更改了某些指令的行为,但这通常不会导致现有代码的任何不兼容性。环 3 也是可用的,并且可以选择用于限制不受信任的代码。另一个区别是系统调用必须作为超调用执行。为了简化对此更改的支持,我们提供了一种机制,该机制可以检测何时从环 0 执行系统调用,并自动将其作为超调用重定向到内核。这是 libDune 中包含的众多功能之一。

libDune is a library created to make it easier to build user programs that make use of Dune. It is completely untrusted by the kernel and consists of a collection of utilities that aid in managing and configuring privileged hardware features. Major components of libDune include a page table manager, an ELF loader, a simple page allocator, and routines that assist user programs in managing exceptions and system calls. libDune is currently 5,898 lines of code.

libDune 是一个库,它的创建是为了使用户程序的构建更容易使用 Dune。它完全不受内核信任,由一系列帮助管理和配置特权硬件功能的实用程序组成。libDune 的主要组件包括一个页表管理器,一个 ELF 加载器,一个简单的页分配器,以及协助用户程序管理异常和系统调用的例程。libDune 目前有 5898 行代码。

We also provide an optional, modified version of libc that uses VMCALL instructions instead of SYSCALL instructions to get a slight performance benefit.

我们还提供了一个可选的、修改过的 libc 版本,它使用 VMCALL 指令而不是 SYSCALL 指令来获得轻微的性能优势。

4.1 启动 Bootstrapping

In many ways, transitioning a process into Dune mode is similar to booting an OS. The first issue is that a valid page table must be provided before enabling Dune. A simple identity mapping is insufficient because, although the goal is to have process addresses remain consistent before and after the transition, the compressed layout of the EPT must be taken into account. After a page table is created, the Dune entry ioctl is called with the page table root as an argument. The Dune module then switches the process to Dune mode and begins executing code, using the provided page table root as the initial %CR3. From there, libDune configures privileged registers to set up a reasonable operating environment. For example, it loads a GDT to provide basic flat segmentation and loads an IDT so that hardware exceptions can be captured. It also sets up a separate stack in the TSS to handle double faults and configures the GS segment base to easily access per-thread data.

在许多方面,将进程转换到 Dune 模式类似于引导操作系统。第一个问题是在启用 Dune 之前必须提供有效的页表。简单的身份映射是不够的,因为尽管目标是使进程地址在转换前后保持一致,但必须考虑 EPT 的压缩布局。创建页表后,使用页表根作为参数调用 Dune 入口 ioctl。然后,Dune 模块将进程切换到 Dune 模式并开始执行代码,使用所提供的页表根作为初始%CR3。在此基础上,libDune 配置特权寄存器以建立合理的操作环境。例如,它加载 GDT 以提供基本的平面分段,并加载 IDT 以捕获硬件异常。它还在 TSS 中设置了一个单独的堆栈来处理双重错误,并配置 GS 段基础以轻松访问每个线程的数据。

4.2 限制 Limitations

Although we can run a wide variety of Linux programs, libDune is still missing some functionality. First, we have not fully integrated support for signals even though they are reported by the Dune module. Applications are required to use dune signal whereas a more compatible solution would override several libc symbols like signal and sigaction. Second, although we support pthreads, some utilities in libDune, such as page table management, are not yet thread-safe. Both of these issues could be resolved with further implementation.

尽管我们可以运行各种各样的 Linux 程序,但 libDune 仍然缺少一些功能。首先,我们没有完全整合对信号的支持,尽管它们是由 Dune 模块报告的。应用程序需要使用 Dune 信号,而一个更兼容的解决方案会覆盖几个 libc 符号,如 signal 和 sigaction。第二,尽管我们支持 pthreads,但 libDune 中的一些实用程序,如页表管理,还不是线程安全的。这两个问题都可以通过进一步的实现来解决。

One unanticipated challenge with working in a Dune environment is that system call arguments must be valid host-virtual addresses, regardless of how guest-virtual mappings are set up. In many ways, this parallels the need to provide physical addresses to hardware devices that perform DMA. In most cases, we can work around the issue by having the guest-virtual address space mirror the host-virtual address space. For situations where this is not possible, walking the user page table to adjust system call argument addresses is necessary.

在 Dune 环境中工作的一个意料之外的挑战是,系统调用参数必须是有效的主机虚拟地址,不管客户虚拟映射是如何设置的。在许多方面,这与为执行 DMA 的硬件设备提供物理地址的需要相似。在大多数情况下,我们可以通过让客户-虚拟地址空间镜像主机-虚拟地址空间来解决这个问题。对于无法做到这一点的情况,有必要遍历用户页表以调整系统调用参数地址。

Another challenge introduced by Dune is that by exposing greater access to privileged hardware, user programs require more architecture-specific code, potentially reducing portability. libDune currently provides an x86centric API, so it is already compatible with AMD machines. However, it should be possible to modify libDune to support non-x86 architectures in a fashion that parallels the construction of many OS kernels. This would require libDune to provide an efficient architecture-independent interface, a topic worth exploring in future revisions.

Dune 引入的另一个挑战是,由于公开了对特权硬件的更多访问权,用户程序需要更多特定架构的代码,可能会降低可移植性。libDune 目前提供了一个以 X86 为中心的 API,因此它已经与 AMD 机器兼容。然而,应该可以修改 libDune 以支持非 x86 架构,其方式与许多操作系统内核的构建相似。这需要 libDune 提供一个有效的与架构无关的接口,这是一个值得在未来修订中探索的话题。

5 应用 Applications

Dune is generic enough that it lets us improve on a broad range of applications. We built two security-related applications, a sandbox and privilege separation system, and one performance-related application, a garbage collector. Our goals were simpler implementations, higher performance, and where applicable, improved security.

Dune 具有足够的通用性,它可以让我们对广泛的应用进行改进。我们构建了两个与安全相关的应用程序(沙盒和权限分离系统)和一个与性能相关的应用程序(垃圾收集器)。我们的目标是更简单的实现,更高的性能,并在适当的地方提高安全性。

5.1 沙盒 Sandboxing

Sandboxing is the process of confining code to restrict the memory it can access and the interfaces or system calls it can use. It is useful for a variety of purposes, such as running native code in web browsers, creating secure OS containers, and securing mobile phone applications. To explore Dune’s potential for these types of applications, we built a sandbox that supports native 64-bit Linux executables.

沙盒是限制代码的进程,以限制它可以访问的内存和它可以使用的接口或系统调用。它可用于多种用途,例如在网络浏览器中运行本地代码,创建安全的操作系统容器,以及保护手机应用程序。为了探索 Dune 在这些类型应用中的潜力,我们建立了一个支持本地 64 位 Linux 可执行文件的沙盒。

The sandbox enforces security through privilege modes by running a trusted sandbox runtime in ring 0 and an untrusted binary in ring 3, both operating within a single address space (on the left of Figure 1, the top and middleboxes respectively). Memory belonging to the sandbox runtime is protected by setting the supervisor bit inappropriate page table entries. Whenever the untrusted binary performs an unsafe operation such as trying to access the kernel through a system call or attempting to modify a privileged state, libDune receives an exception and jumps into a handler provided by the sandbox runtime. In this way, the sandbox runtime can filter and restrict the behavior of the untrusted binary.

沙盒通过特权模式实现安全,在 0 环运行一个受信任的沙盒运行时,在 3 环运行一个不受信任的二进制,两者都在一个地址空间内运行(在图 1 的左边,分别在顶部和中部)。属于沙盒运行时的内存通过设置不适当的页表项的监督者位来进行保护。每当不受信任的二进制文件执行不安全的操作,如试图通过系统调用访问内核或试图修改特权状态,libDune 就会收到一个异常,并跳转到沙盒运行时提供的处理程序。通过这种方式,沙盒运行时可以过滤和限制不受信任的二进制文件的行为。

While we rely on the kernel to load the sandbox runtime, the untrusted binary must be loaded in userspace. One risk is that it could contain maliciously crafted headers designed to exploit flaws in the ELF loader. We hardened our sandbox against this possibility by using two separate ELF loaders. First, the sandbox runtime uses a minimal ELF loader (part of libDune), that only supports static binaries, to load a second ELF loader into the untrusted environment. We choose to use ld-linux.so as our second ELF loader because it is already used as an integral and trusted component in Linux. Then, the sandbox runtime executes the untrusted environment, allowing the second ELF loader to load an untrusted binary entirely from ring 3. Thus, even if the untrusted binary is malicious, it does not have a greater opportunity to attack the sandbox during ELF loading than it would while running inside the sandbox normally.

虽然我们依靠内核来加载沙盒运行时,但不受信任的二进制文件必须在用户空间加载。一个风险是,它可能包含恶意制作的头文件,旨在利用 ELF 加载器的缺陷。我们通过使用两个独立的 ELF 加载器来加强我们的沙盒,以防止这种可能性。首先,沙盒运行时使用一个最小的 ELF 加载器(libDune 的一部分),它只支持静态二进制文件,将第二个 ELF 加载器加载到不受信任的环境中。我们选择使用 ld-linux.so 作为我们的第二个 ELF 加载器,因为它已经被用作 Linux 中不可或缺的可信组件。然后,沙盒运行时执行不可信环境,允许第二个 ELF 加载程序完全从环 3 加载不可信二进制文件。因此,即使不受信任的二进制文件是恶意的,它在 ELF 加载期间攻击沙盒的机会也不会比在沙盒内正常运行时攻击沙盒的机会更大。

So far our sandbox has been applied primarily as a tool for filtering Linux system calls. However, it could potentially be used for other purposes, including providing a completely new system call interface. For system call filtering, a large concern is to prevent the execution of any system call that could corrupt or disable the sandbox runtime. We protect against this hazard by validating each system call argument, checking to make sure performing the system call would not allow the untrusted binary to access or modify memory belonging to the sandbox runtime. We do not yet support all system calls, but we support enough to run most single-threaded Linux applications. However, nothing prevents supporting multi-threaded programs in the future.

到目前为止,我们的沙盒主要用作过滤 Linux 系统调用的工具。但是,它可以潜在地用于其他目的,包括提供全新的系统调用接口。对于系统调用过滤,一个大问题是防止执行任何可能破坏或禁用沙盒运行时的系统调用。我们通过验证每个系统调用参数来防止这种危险,检查以确保执行系统调用不会允许不受信任的二进制文件访问或修改属于沙盒运行时的内存。我们还不支持所有的系统调用,但我们支持的系统调用足以运行大多数单线程 Linux 应用程序。但是,没有什么可以阻止将来支持多线程程序。

We implemented two policies on top of the sandbox. Firstly, we support a null policy that allows system calls to pass through but still validates arguments to protect the sandbox runtime. It is intended primarily to demonstrate raw performance overhead. Secondly, we support a userspace firewall. It uses system call interposition to inspect important network system calls, such as bind and connect and prevents communication with undesirable parties as specified by a policy description.

我们在沙盒之上实施了两个策略。首先,我们支持空策略,该策略允许系统调用通过,但仍然验证参数以保护沙盒运行时。它主要用于演示原始性能开销。其次,我们支持用户空间防火墙。它使用系统调用插入来检查重要的网络系统调用,如 bind 和 connect,并防止与策略描述所指定的不受欢迎的一方进行通信。

To further demonstrate the flexibility of our sandbox, we also implemented a checkpointing system that can serialize an application to disk and then restore execution at a later time. This includes saving memory, registers, and system call state (e.g., open file descriptors).

为了进一步展示沙盒的灵活性,我们还实现了一个检查点系统,该系统可以将应用程序序列化到磁盘,然后在稍后恢复执行。这包括保存内存、寄存器和系统调用状态(例如,打开的文件描述符)。

5.2 Wedge

Wedge [10] is a privilege separation system. Its core abstraction is a sthread which provides fork-like isolation with pthread-like performance. A sthread is a lightweight process that has access to memory, file descriptors and system calls as specified by a policy. The idea is to run risky code in a sthread so that any exploits will be contained within it. In a web server, for example, each client request would run in a separate sthread to guarantee isolation between users. To make this practical, sthreads need fast creation (e.g., one per request) and context switch time. Fast creation can be achieved through sthread recycling. Instead of creating and killing a sthread each time, a sthread is checkpointed on its first creation (while still pristine and unexploited) and restored on exit so that it can be safely reused upon the next creation request. Doing so reduces the sthread creation cost to the (cheaper) cost of restoring memory.

Wedge [10] 是一个权限分离系统。它的核心抽象是一个 sthread,它提供了类似 fork 的隔离和类似 pthread 的性能。一个 sthread 是一个轻量级的进程,它可以按照策略的规定访问内存、文件描述符和系统调用。其原理是在 sthread 中运行有风险的代码,这样任何漏洞都会被包含在其中。例如,在一个网络服务器中,每个客户的请求都会在一个单独的 sthread 中运行,以保证用户之间的隔离。为了使这一点切实可行,sthreads 需要快速的创建(例如,每次请求都创建一个)和上下文切换时间。快速创建可以通过 sthread 回收来实现。与其每次都创建并杀死一个 sthread,不如在第一次创建 sthread 时对其进行检查点处理(当它还是原始的、未被利用的时候),并在退出时进行恢复,这样它就可以在下一次创建请求时被安全地重新使用。这样做将 sthread 的创建开销降低到恢复内存的开销(更便宜)。

Wedge uses many of Dune’s hardware features. Ring protection is used to enforce system call policies; page tables limit what memory sthreads can access; dirty bits are used to restore memory during sthread recycling, and the tagged TLB is used for fast context switching.

Wedge 使用了许多 Dune 的硬件特性。环形保护被用来执行系统调用策略;页表限制了 sthreads 可以访问的内存;脏位被用来在 sthread 回收过程中恢复内存,并且标记 TLB 被用来进行快速上下文切换。

5.3 垃圾回收 Garbage Collection

Garbage collectors (GC) often utilize memory management hardware to speed up a collection [28]. Appel and Li [5] explain several techniques that use standard user-level virtual memory protection operations, whereas Azul Systems [15, 36] went to the extent of modifying the kernel and system call interface. By contrast, Dune provides a clean and efficient way to access relevant hardware directly. The features provided by Dune that are of interest to garbage collectors include:

垃圾收集器(GC)通常利用内存管理硬件来加速收集[28]。Appel 和 Li[5]解释了几种使用标准用户级虚拟内存保护操作的技术,而 Azul Systems[15,36]则修改了内核和系统调用接口。相比之下,Dune 提供了一种直接访问相关硬件的干净高效的方式。Dune 提供的垃圾收集器感兴趣的功能包括:

Fast faults. GCs often use memory protection and fault handling to implement read and write barriers.

快速错误。GC 通常使用内存保护和错误处理来实现读写屏障。

Dirty bits. Knowing what memory has been touched since the last collection enables optimizations and can be a core part of the algorithm.

脏位。知道自上次收集以来有哪些内存被触及,可以实现优化,并且可以成为算法的核心部分。

Page table. One optimization in a moving GC is to free the underlying physical frame without freeing the virtual page it was backing. This is useful when the data has been moved but references to the old location remain and can still be caught through page faults. Remapping memory can also be performed to reduce fragmentation.

页表。移动 GC 中的一个优化是释放底层物理帧,而不释放它所支持的虚拟页。当数据已被移动,但对旧位置的引用仍然存在,并且仍然可以通过页面错误捕获时,这很有用。还可以重新映射内存以减少碎片。

TLB control. GCs often manipulate memory mappings at high rates, making control over TLB invalidation very useful. If it can be controlled, mapping manipulations can be effectively batched, rendering certain algorithms more feasible.

TLB 控制。GC 经常以很高的速度操纵内存映射,这使得对 TLB 失效的控制非常有用。如果可以控制,映射操作可以有效地分批进行,使某些算法更加可行。

We modified the Boehm GC [12] to use Dune to improve performance. The Boehm GC is a robust mark-sweep collector that supports parallel and incremental collection. It is designed either to be used as a conservative collector with C/C++ programs, or by the compiler and run-time backends where the conservativeness can be controlled. It is widely used, including by the Mono project and GNU Objective C.

我们修改了 Boehm GC [12],使用 Dune 来提高性能。Boehm GC 是一个强大的标记扫描收集器,支持并行和增量收集。它被设计成与 C/C++程序一起使用的保守收集器,或者由编译器和运行时后端使用,其中保守性可以被控制。它被广泛使用,包括 Mono 项目和 GNU Objective C。

An important implementation question for the Boehm GC is how dirty pages are discovered and managed. The two original options were

Boehm GC 的一个重要实现问题是如何发现和管理脏页。最初的两个选项是

utilizing mprotect and signal handlers to implement its dirty bit tracking, or

利用 mprotect 和信号处理程序来实现其脏位跟踪,或

utilizing OS-provided dirty bit read methods such as the Win32 API call GetWriteWatch.

利用操作系统提供的脏位读取方法,如 Win32 API 调用 GetWriteWatch。

In Dune we support and improve both methods.

在 Dune 中,我们支持并改进这两种方法。

A direct port to Dune already gives a performance improvement because mprotect can directly manipulate the page table and a page fault can be handled directly without needing an expensive SIGSEGV signal. The GC manipulates single pages 90% of the time, so we were able to improve performance further by using the INVPLG instruction to flush only a single page instead of the entire TLB. Finally, in Dune, the Boehm GC can access dirty bits directly without having to emulate this functionality. Some OSes provide system calls for reading page table dirty bits. Not all of these interfaces are well matched to GC—for instance, SunOS examines the entire virtual address space rather than permit queries for a particular region. Linux provides no user-level access at all too dirty bits.

直接移植到 Dune 已经有了性能上的提高,因为 mprotect 可以直接操作页表,并且可以直接处理页面错误,而不需要昂贵的 SIGSEGV 信号。GC 在 90% 的时间里操作单页,所以我们能够通过使用 INVPLG 指令只刷新单页而不是整个 TLB 来进一步提高性能。最后,在 Dune 中,Boehm GC 可以直接访问脏位,而不必模拟此功能。一些操作系统为读取页表脏位提供了系统调用。并非所有这些接口都与 GC 很匹配——例如,SunOS 检查整个虚拟地址空间,而不允许对某个特定区域进行查询。Linux 完全没有提供用户级的脏位访问。

The work done on the Boehm GC represents a straightforward application of Dune to a GC. It is worth also examining the changes made by Azul Systems to Linux so that they could support their C4 GC [36] and mapping this to the support provided by Dune:

在 Boehm GC 上完成的工作代表了 Dune 在 GC 上的直接应用。还值得研究的是 Azul Systems 对 Linux 所做的更改,以便他们可以支持他们的 C4 GC [36],并将其映射到 Dune 提供的支持:

Fast faults. Azul modified the Linux memory protection and mapping primitives to greatly improve performance, part of this included allowing hardware exceptions to bypass the kernel and be handled directly by user mode.

快速错误。Azul 修改了 Linux 内存保护和映射原语以极大地提高性能,其中包括允许硬件异常绕过内核并由用户模式直接处理。

Batched page table. Azul enabled explicit control of TLB invalidation and a shadow page table to expose a prepare and commit style API for batching page table manipulation.

批处理页表。Azul 启用了对 TLB 无效和影子页表的显式控制,为批处理页表的操作提供了一个准备和提交风格的 API。

Shatter/Heal. Azul enabled large pages to be ‘shattered’ into small pages or a group of small pages to be ‘healed’ into a single large page.

打碎/修复。Azul 支持将大页 “打碎 “成小页,或将一组小页 “修复 “成一个大页。

Free physical frames. When the Azul C4 collector frees an underlying physical frame, it will trap access to the unmapped virtual pages to catch old references.

释放物理帧。当 Azul C4 收集器释放底层物理帧时,它将捕获对未映射虚拟页面的访问,以捕获旧的引用。

All of the above techniques and interfaces can be implemented efficiently on top of Dune, with no need for any kernel changes other than loading the Dune module.

上述所有技术和接口都可以在 Dune 上有效地实现,除了加载 Dune 模块外,不需要进行任何内核更改。

6 评估 Evaluation

In this section, we evaluate the performance and utility of Dune. Although using VT-x has an intrinsic cost, in most cases, Dune’s overhead is relatively minor. On the other hand, Dune offers significant opportunities to improve security and performance for applications that can take advantage of access to privileged hardware features.

在本节中,我们将评估 Dune 的性能和效用。虽然使用 VT-x 有内在的开销,但在大多数情况下,Dune 的开销相对较小。另一方面,Dune 为那些能够利用特权硬件功能的应用程序提供了改善安全和性能的重要机会。

All tests were performed on a single-socket machine with an Intel Xeon E3-1230 v2 (a four-core Ivy Bridge CPU clocked at 3.3 GHz) and 16GB of RAM. We installed a recent 64-bit version of Debian Linux that includes Linux kernel version 3.2. Power management features, such as frequency scaling, were disabled.

所有测试均在配备 Intel Xeon E3-1230 v2(时钟频率为 3.3 GHz 的四核 Ivy Bridge CPU)和 16GB RAM 的单插槽机器上进行。我们安装了最新的 64 位版本的 Debian Linux,其中包括 Linux 内核版本 3.2。电源管理功能(如频率调整)被禁用。

6.1 在 Dune 中运行的开销 Overhead from Running in Dune

Performance in Dune is impacted by two main sources of overhead. First, VT-x increases the cost of entering and exiting the kernel—VM entries and VM exits are more expensive than fast system call instructions or exceptions. As a result, both system calls and other types of faults (e.g., page faults) must pay a fixed cost in Dune. Second, using the EPT makes TLB misses more expensive because, in some cases, the hardware page walker must traverse two-page tables instead of one.

Dune 中的性能受到两个主要开销来源的影响。首先,VT-x 增加了进入和退出内核的开销——VM 进入和 VM 退出比快速系统调用指令或异常更昂贵。因此,在 Dune 中,系统调用和其他类型的错误(例如,页面错误)都必须付出固定的代价。其次,使用 EPT 使得 TLB 未命中的代价更高,因为在某些情况下,硬件页面查询器必须遍历两个而不是一个页表。

We built synthetic benchmarks to measure both of these effects. Table 2 shows the overhead of system calls, page faults, and page table walks. For system calls, we manually performed getpid, an essentially null system call (worst case for Dune), and measured the round-trip latency. For page faults, we measured the time it took to a fault in a pre-zeroed memory page by the kernel. Finally, for page table walks, we measured the time spent filling a TLB miss.

我们建立了综合基准来衡量这两种影响。表 2 显示了系统调用、页面错误和页表遍历的开销。对于系统调用,我们手动执行 getpid,这是一个本质上为空的系统调用(Dune 的最坏情况),并测量往返延迟。对于页面错误,我们测量了内核在预先清零的内存页面中发生错误所花费的时间。最后,对于页表遍历,我们测量了填充 TLB 未命中所花费的时间。

| getpid | page fault | page walk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linux | 138 | 2687 | 35.8 |

| Dune | 895 | 5093 | 86.4 |

Table 2: Average time (in cycles) of operations that have overhead in Dune compared to Linux.

表 2: 与 Linux 相比,Dune 中具有开销的操作的平均时间(以周期为单位)。

| ptrace | trap | appel1 | appel2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linux | 27317 | 2821 | 701413 | 684909 |

| Dune | 1091 | 587 | 94496 | 94854 |

Table 3: Average time (in cycles) of operations that are faster in Dune compared to Linux.

表 3: 与 Linux 相比,Dune 中更快的操作的平均时间(以周期为单位)。

Measuring TLB miss overhead required us to build a simple memory stress tool. It works by performing a random page-aligned walk across 216 memory pages. This model a workload with poor memory locality, as nearly every memory access results in a last-level TLB miss. We then divided the total number of cycles spent waiting for page table walks, as reported by a performance counter, by the total number of memory references, giving us a cycle cost per page walk.

测量 TLB 未命中开销需要我们构建一个简单的内存压力工具。它的工作原理是在 216 个内存页面上执行随机的页面对齐遍历。此模型的工作负载具有较差的内存局部性,因为几乎每次内存访问都会导致最后一级 TLB 未命中。然后,我们将性能计数器报告的等待页表遍历所花费的周期总数除以内存引用总数,得到每个页的遍历开销。

In general, the overhead Dune adds has only a small effect on end-to-end performance, as we show in Section 6.3. For system calls, the time spent in the kernel tends to be a larger cost than the fixed VMX mode transition costs. Page fault overhead is also not much of a concern, as page faults tend to occur infrequently during normal use, and direct access to exception hardware is available when higher performance is required. On the other hand, Dune’s use of the EPT does impact performance in certain workloads. For applications with good memory locality or a small working set, it has no impact because the TLB hit rate is sufficiently high. However, for applications with poor memory locality or a large working set, more frequent TLB misses result in a measurable slowdown. One effective strategy for limiting this overhead is to use large pages. We explore this possibility further in section 6.3.1.

一般来说,Dune 增加的开销对端到端的性能只有很小的影响,正如我们在第 6.3 节中显示的那样。对于系统调用,在内核中花费的时间往往比固定的 VMX 模式转换开销更大。页面错误开销也不是什么大问题,因为在正常使用过程中,页面错误往往不常发生,而且在需要更高的性能时,可以直接访问异常硬件。另一方面,Dune 对 EPT 的使用确实影响了某些工作负载的性能。对于具有良好的内存局部性或小工作集的应用程序,它没有影响,因为 TLB 的命中率足够高。然而,对于内存局部性较差或工作集较大的应用程序,更频繁的 TLB 未命中会导致明显的速度减慢。限制这种开销的一个有效策略是使用大页。我们将在 6.3.1 节中进一步探讨这种可能性。

6.2 Dune 实现的优化 Optimizations Made Possible by Dune

Access to privileged hardware features creates many opportunities for optimization. Table 3 shows the speedups we achieved in the following OS workloads:

对特权硬件功能的访问为优化创造了许多机会。表 3 显示了我们在以下操作系统工作负载中实现的加速:

ptrace is a measure of system call interposition performance. This is the cost of a Linux process intercepting a system call (getpid) with ptrace, forwarding the system call to the kernel, and returning the result. In Dune this is the cost of intercepting a system call directly using ring protection in VMX non-root mode, forwarding the system call through a VMCALL, and returning the result. An additional scenario is where applications wish to intercept system calls but not forward them to the kernel and instead just implement them internally. PTRACE SYSEMU is the most efficient mechanism for doing so since ptrace requires forwarding a call to the kernel. The latency of intercepting a system call with PTRACE SYSEMU is 13,592 cycles. In Dune this can be implemented by handling the hardware system call trap directly, with a latency of just 180 cycles. This reveals that most of the Dune ptrace benchmark overhead was forwarding the getpid system call via a VMCALL rather than intercepting the system call.

ptrace 是一个衡量系统调用插值性能的指标。这是一个 Linux 进程用 trace 拦截系统调用(getpid),将系统调用转发给内核,并返回结果的开销。在 Dune 中,这是在 VMX 非 root 模式下使用环保护直接拦截系统调用,通过 VMCALL 转发系统调用,并返回结果的开销。另外一种情况是,应用程序希望拦截系统调用,但不把它们转发到内核,而只是在内部实现它们。PTRACE SYSEMU 是最有效的机制,因为 trace 需要转发一个调用到内核。用 PTRACE SYSEMU 拦截一个系统调用的延迟是 13592 个周期。在 Dune 中,这可以通过直接处理硬件系统调用陷阱来实现,其延迟仅为 180 个周期。这表明,Dune ptrace 基准的大部分开销是通过 VMCALL 转发 getpid 系统调用,而不是拦截系统调用。

trap indicates the time it takes for a process to get an exception for a page fault. We compare the latency of a SIGSEGV signal in Linux with a hardware-generated page fault in Dune.

trap 表示进程获取页面错误异常所需的时间。我们将 Linux 中 SIGSEGV 信号的延迟与 Dune 中硬件生成的页面错误进行了比较。

appel1 is a measure of user-level virtual memory management performance. It corresponds to the TRAP, PROT1, and UNPROT test described in [5], where 100 protected pages are accessed, causing faults. Then, in the fault handler, the faulting page is unprotected, and a new page is protected.

appel1 是一个衡量用户级虚拟内存管理性能的指标。它对应于[5]中描述的 TRAP、PROT1 和 UNPROT 测试,其中 100 个受保护的页面被访问,导致错误。然后,在错误处理程序中,发生错误的页面被解除保护,新的页面被保护。

appel2 is another measure of user-level virtual memory management performance. It corresponds to the PROTN, TRAP, and UNPROT test described in [5], where 100 pages are protected. Then each is accessed, with the fault handler unprotecting the faulting page.

appel2 是另一个衡量用户级虚拟内存管理性能的指标。它对应于[5]中描述的 PROTN、TRAP 和 UNPROT 测试,其中 100 页被保护。然后每个页面都被访问,错误处理程序会解除对错误页面的保护。

6.3 应用表现 Application Performance

6.3.1 沙盒 Sandbox

We evaluated the performance of our sandbox by running two types of workloads. First, we tested compute performance by running SPEC2000. Second, we tested IO performance by running Lighttpd. The null sandbox policy was used in both cases.

我们通过运行两种类型的工作负载来评估沙盒的性能。首先,我们通过运行 SPEC2000 来测试计算性能。其次,我们通过运行 lighttpd 来测试 IO 性能。两种情况下都使用了空沙盒策略。

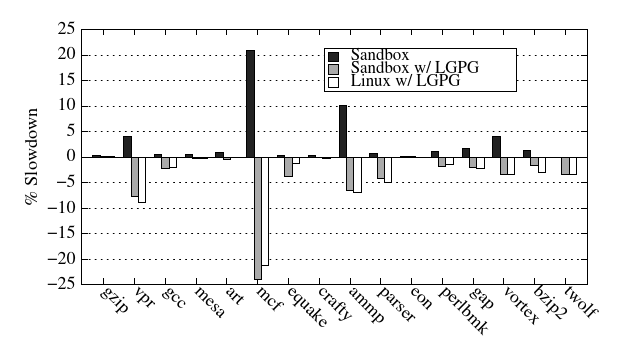

Figure 3 shows the performance of SPEC2000. In general, the sandbox had very low overhead, averaging only 2.9% percent slower than Linux. However, the mcf and ammp benchmarks were outliers, with 20.9% and 10.1% slowdowns respectively. This deviation in performance can be explained by EPT overhead, as we observed a high TLB miss rate. We also measured SPEC2000 in VMware Player, and, as expected, EPT overhead resulted in very similar drops in performance.

图 3 显示了 SPEC2000 的性能。一般来说,沙盒的开销非常低,平均只比 Linux 慢 2.9%。然而,mcf 和 amp 基准是异常值,分别慢了 20.9% 和 10.1%。这种性能上的偏差可以用 EPT 开销来解释,因为我们观察到很高的 TLB 未命中率。我们还在 VMware Player 中测量了 SPEC2000,正如预期的那样,EPT 开销导致的性能下降非常相似。

Figure3: Average SPEC2000 slowdown compared to Linux for the sandbox, the sandbox using large pages, and Linux using large pages identically.

图 3: 与 Linux 相比,沙盒、使用大页面的沙盒和使用大页面的 Linux 的平均 SPEC2000 减速情况相同。

We then adjusted the sandbox to avoid EPT overhead by backing large memory allocations with 2MB large pages, both in the EPT and the user page table. Supporting this optimization was straightforward because we were able to intercept mmap calls and transparently modify them to use large pages. Such an approach does not cause much memory fragmentation because large pages are only used selectively. To perform a direct comparison, we tested SPEC2000 in a modified Linux environment that identically allocates large pages using libhugetlbfs [1]. When large pages were used for both, average performance in the sandbox and Linux was nearly identical (within 0.1%).

| 1 client | 100 clients | |

|---|---|---|

| Linux | 2236 | 24609 |

| Dune sandbox | 2206 | 24255 |

| VMWare Player | 734 | 5763 |

Table 4: Lighttpd performance (in requests per second).

表 4: Lighttpd 的性能(以每秒请求数计)。

然后,我们调整了沙盒,以避免 EPT 的开销,在 EPT 和用户页表中都用 2MB 的大页来支持大的内存分配。支持这种优化是直接的,因为我们能够拦截 mmap 调用并透明地修改它们以使用大页。这种方法不会造成很大的内存碎片,因为大页只是被有选择地使用。为了进行直接比较,我们在一个修改过的 Linux 环境中测试了 SPEC2000,该环境使用 libhugetlbfs[1]来分配大页面。当大页面被用于两者时,沙盒和 Linux 的平均性能几乎相同(在 0.1%以内)。

Table 4 shows the performance of Lighttpd, a single-threaded, single-process, event-based HTTP server. Lighttpd exercises the kernel to a much greater extent than SPEC2000, making frequent system calls and putting a load on the network stack. Lighttpd performance was measured over Gigabit Ethernet using the Apache ab benchmarking tool. We configured ab to repeatedly retrieve a small HTML page over the network with different levels of concurrency: 1 client for measuring latency and 100 clients for measuring throughput.

表 4 显示了 Lighttpd 的性能,这是一个单线程、单进程、基于事件的 HTTP 服务器。与 SPEC2000 相比,Lighttpd 在更大程度上使用内核,进行频繁的系统调用并给网络堆栈增加负载。Lighttpd 性能是使用 Apache AB 基准测试工具在千兆以太网上测量的。我们将 AB 配置为在网络上重复检索具有不同并发级别的小 HTML 页面:1 个客户端用于测量延迟,100 个客户端用于测量吞吐量。

| create | ctx switch | http request | |

|---|---|---|---|

| fork | 81 | 0.49 | 454 |

| Dune sthread | 2 | 0.15 | 362 |

Table 5: Wedge benchmarks (times in microseconds).

表 5: Wedge 基准(时间以微秒计)

We found that the sandbox incurred only a slight slowdown, less than 2% for both the latency and throughput test. This slowdown can be explained by Dune’s higher system call overhead. Using strace, we determined that Lighttpd was performing several system calls per connection, causing frequent VMX transitions. However, VMware Player, a conventional VMM, experienced much greater overhead: 67% for the latency test and 77% for the throughput test. Although VMware Player pays VMX transition costs too, the primary reason for the slowdown is that each network request must traverse two network stacks, one in the guest and one in the host.

我们发现沙盒只有轻微的减速,在延迟和吞吐量测试中都不到 2%。这种减速可以用 Dune 较高的系统调用开销来解释。使用 strace,我们确定 lighttpd 在每个连接上执行了几个系统调用,导致了频繁的 VMX 转换。然而,VMwarePlayer(一种传统的 VMM)的开销要大得多:延迟测试为 67%,吞吐量测试为 77%。尽管 VMware Player 也有 VMX 转换开销,但速度减慢的主要原因是每个网络请求必须穿越两个网络堆栈,一个在客户中,一个在主机中。

We also found that the sandbox provides an easily extensible framework that we used to implement checkpointing and our firewall. The checkpointing implementation consisted of approximately 450 SLOC with 50 of those being enhancements to the sandbox loader. Our firewall was around 200 SLOC with half of that being the firewall rules parser.

我们还发现,沙盒提供了一个易于扩展的框架,我们用它来实现检查点和防火墙。检查点实现由大约 450 个 SLOC 组成,其中 50 个是对沙盒加载器的增强。我们的防火墙大约有 200 个 SLOC,其中一半是防火墙规则解析器。

6.3.2 Wedge

Wedge has two main benchmarks: sthread creation and context switch time. These are compared to fork, the system call used today to implement privilege separation. As shown in Table 5, sthread creation is faster than fork because instead of creating a new process each time, a sthread is reused from a pool and “recycled” by restoring dirty memory and state. Context switch time in sthreads is low because TLB flushes are avoided by using the tagged TLB. In Dune sthreads are created 40× faster than processes and the context switch time is 3× faster. In previous Wedge implementations, sthread creation was 12× faster than a fork with no improvement in context switch time [9]. Dune is faster because it can leverage the tagged TLB and avoid kernel calls to create sthreads. The last column of Table 5 shows an application benchmark of a web server serving a static file on a LAN where each request runs in a newly forked process or sthread for isolation. Dune sthreads show a 20% improvement here.

Wedge 有两个主要的基准:sthread 创建和上下文切换时间。这些都是与 fork 进行比较的,fork 是今天用来实现权限分离的系统调用。如表 5 所示,sthread 的创建比 fork 要快,因为 sthread 不是每次都创建一个新的进程,而是从一个池中重复使用,并通过恢复脏内存和状态来 “循环使用”。sthreads 的上下文切换时间很低,因为通过使用标签 TLB 避免了 TLB 的刷新。在 Dune 中,sthreads 的创建速度比进程快 40 倍,上下文切换时间也快 3 倍。在以前的 Wedge 实现中,sthread 的创建比 fork 快 12 倍,而上下文切换时间没有改善[9]。Dune 更快,因为它可以利用标记的 TLB 并避免内核调用来创建 sthreads。表 5 的最后一列显示了在 LAN 上为静态文件提供服务的 Web 服务器的应用程序基准测试,每个请求都在一个新 fork 的进程或 sthread 中运行,以达到隔离的目的。Dune sthreads 在这里显示了 20%的改进。

The original Wedge implementation consisted of a 700line kernel module and a 1,300-line library. A userspace-only implementation of Wedge exists, though the authors lamented that POSIX did not offer adequate APIs for memory and system call protection, hence the result was a very complicated 5,000-line implementation [9]. Dune instead exposes the hardware protection features needed for a simple implementation, consisting of only 750 lines of user code.

最初的 Wedge 实现由一个 700 行的内核模块和一个 1300 行的库组成。Wedge 的纯用户空间实现是存在的,尽管作者感叹 POSIX 没有为内存和系统调用保护提供足够的 API,因此结果是一个非常复杂的 5000 行实现[9]。Dune 反而公开了一个简单实现所需的硬件保护功能,只包括 750 行的用户代码。

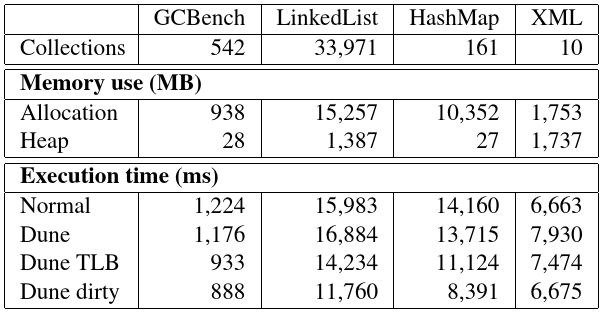

Table 6: Performance numbers of the GC benchmarks.

表 6:GC 基准的性能数字。

6.3.3 垃圾回收 Garbage Collector

We implemented three different sets of modifications to the Boehm GC. The first is the simplest port possible with no attempt to utilize any advanced features of Dune. This benefits from Dune’s fast memory protection and fault handling but suffers from the extra TLB costs. The second version improves the direct port by carefully controlling when the TLB is invalidated. The third version avoids using memory protection altogether, instead, it reads the dirty bits directly. The direct port required changing 52 lines, the TLB optimized version 91 lines, and the dirty bit version 82 lines.

我们对 Boehm GC 进行了三组不同的修改。第一个是最简单的移植,没有尝试利用 Dune 的任何高级功能。这得益于 Dune 的快速内存保护和错误处理,但受到额外 TLB 开销的影响。第二个版本通过仔细控制 TLB 的失效时间来改进直接移植。第三个版本完全避免使用内存保护,相反,它直接读取脏位。直接端口需要改变 52 行,TLB 优化版本需要 91 行,而脏位版本需要 82 行。

To test the performance improvements of these changes we used the following benchmarks:

为了测试这些更改带来的性能改进,我们使用了以下基准测试:

GCBench [11]. A microbenchmark wrote by Hans Boehm and widely used to test garbage collector performance. In essence, it builds a large binary tree.

GCBench [11]. 由 Hans Boehm 编写的一个微基准,广泛用于测试垃圾收集器的性能。实质上,它构建了一个大型二叉树。

Linked List. A microbenchmark that builds increasingly large linked lists of integers, summing each one after it is built.

链表。构建越来越大的整数链表的微准测试,在构建后对每个整数链表求和。

Hash Map. A microbenchmark that utilizes the Google sparse hash map library [23] (C version).

哈希表。利用 Google 稀疏哈希表库[23](C 版本)的微基准测试。

XML Parser. A full application that uses the MiniXML library [34] to parse a 150MB XML file containing medical publications. It then counts the number of publications each author has using a hash map.

XML 解析器。一个完整的应用程序,使用 MiniXML 库[34]来解析一个包含医学出版物的 150MB 的 XML 文件。然后,它使用一个哈希表计算每个作者拥有的出版物数量。

The results for these benchmarks are presented in Table 6. The direct port displays mixed results due to the improvement to memory protection and the fault handler but slowdown of EPT overhead. As soon as we start using more hardware features, we see a clear improvement over the baseline. Other than the XML Parser, the TLB version improves performance between 10.9% and 23.8% and the dirty bit version between 26.4% and 40.7%.

这些基准测试的结果见表 6。由于对内存保护和错误处理程序的改进,直接移植显示出混合的结果,但 EPT 开销降低。一旦我们开始使用更多的硬件特性,我们就会看到有明显的改善。除了 XML 解析器以外,TLB 版本的性能提高了 10.9%到 23.8%,脏位版本的性能提高了 26.4%到 40.7%。

The XML benchmark is interesting as it shows a slowdown under Dune for all three versions: 19.0%, 12.2%, and 0.2% slower for the direct, TLB, and dirty versions respectively. This appears to be caused by EPT overhead, as the benchmark does not create enough garbage to benefit from the modifications we made to the Boehm GC. This is indicated in Table 6; the total amount of allocation is nearly equal to the maximum heap size. We verified this by modifying the benchmark to instead take a list of XML files, processing each sequentially so that memory would be recycled. We then saw a linear improvement in the Dune versions over the baseline as the number of files increased. With ten 150MB XML files as input, the dirty bit version of the Boehm GC showed a 12.8% improvement in execution time over the baseline.

XML 基准测试很有趣,因为它显示了所有三个版本在 Dune 下的减速:Direct、TLB 和 Dirty 版本分别慢了 19.0%、12.2%和 0.2%。这似乎是由 EPT 开销引起的,因为基准测试没有创建足够的垃圾来从我们对 Boehm GC 所做的修改中获益。如表 6 所示。分配的总量几乎等于最大堆大小。我们通过修改基准测试来验证这一点:按顺序处理每个文件以取代 XML 文件列表,以便回收内存。然后,我们看到随着文件数量的增加,Dune 版本线性的改善。使用 10 个 150MB 的 XML 文件作为输入,Boehm GC 的脏位版本在执行时间上提高了 12.8%。

7 对硬件的思考 Reflections on Hardware

While developing Dune, we found VT-x to be a surprisingly flexible hardware mechanism. In particular, the fine-grained control provided by the VMCS allowed us to precisely direct how the hardware was exposed. However, some hardware changes to VT-x could benefit Dune. One noteworthy area is the EPT, as we encountered both performance overhead and implementation challenges. Hardware modifications have been proposed to mitigate EPT overhead [2, 8]. In addition, modifying the EPT to support the same address width as the regular page table would reduce the complexity of our implementation and improve coverage of the process address space. Further reductions to VM exit and VM entry latency could also benefit Dune. However, we were able to aggressively optimize hypercalls, and VMX transition costs had only a small effect on the performance of the applications we evaluated.

在开发 Dune 时,我们发现 VT-x 是一种非常灵活的硬件机制。特别是,VMCS 提供的细粒度控制使我们能够精确地指导如何公开硬件。但是,对 VT-x 的一些硬件更改可能会使 Dune 受益。一个值得注意的领域是 EPT,因为我们遇到了性能开销和实现挑战。已有人提议对硬件进行修改以减轻 EPT 的开销[2,8]。此外,修改 EPT 以支持与常规页表相同的地址宽度将降低我们实现的复杂性,并提高进程地址空间的覆盖率。进一步减少 VM 退出和 VM 进入延迟也会使 Dune 受益。但是,我们能够积极优化虚拟化调用,并且 VMX 过渡开销对我们评估的应用程序的性能只有很小的影响。

There are a few hardware features that we have not yet exposed, even though they are available in VT-x and possible to support in Dune. Most seem useful only in special situations. For example, a user program might want to have control over caching to prevent information leakage. However, this would only be effective if CPU affinity could be controlled. As another example, access to efficient polling instructions (i.e., MONITOR and MWAIT) could be useful in reducing power consumption for userspace messaging implementations that perform cache line polling. Finally, exposing access to debug registers could allow user programs to more efficiently set up memory watchpoints.

有一些硬件功能我们还没有公开,尽管它们在 VT-x 中可用,并且可能在 Dune 中得到支持。大多数似乎只有在特殊情况下才有用。例如,用户程序可能希望控制缓存以防止信息泄漏。但是,只有在可以控制 CPU 关联的情况下,这才会有效。作为另一示例,对高效轮询指令(即,MONITOR 和 MWAIT)的访问在降低执行高速缓存线轮询的用户空间消息收发实现的功耗方面可能是有用的。最后,公开对调试寄存器的访问可以允许用户程序更有效地设置内存观察点。

It may also be useful to provide Dune applications with direct access to IO devices. Many VT-x systems include support for an IOMMU, a device that can be used to make DMA access safe even when it is available to untrusted software. Thus, Dune could be modified to safely expose certain hardware devices. A potential benefit could be reduced IO latency. The availability of SR-IOV makes this possibility more practical because it allows a single physical device to be partitioned across multiple guests.

为 Dune 应用程序提供对 IO 设备的直接访问也可能是有用的。许多 VT-x 系统包括对 IOMMU 的支持,IOMMU 是一种可用于使 DMA 访问安全的设备,即使它可用于不受信任的软件。因此,可以修改 Dune 以安全地公开某些硬件设备。一个潜在的好处是可以减少 IO 延迟。SR-IOV 的可用性使这种可能性变得更加实际,因为它允许在多个客户机之间对单个物理设备进行分区。

Recently, a variety of non-x86 hardware platforms have gained support for hardware-assisted virtualization, including ARM [38], Intel Itanium [25], and IBM Power [24]. ARM is of particular interest because of its prevalence in mobile devices, making the ARM Virtualization Extensions an obvious future target for Dune. ARM’s support for virtualization is similar to VT-x in some areas. For example, ARM is capable of exposing direct access to privileged hardware features, including exceptions, virtual memory, and privilege modes. Moreover, ARM provides a System MMU, which is comparable to the EPT. ARM’s most significant difference is that it introduces a new deeper privilege mode called Hyp that runs underneath the guest kernel. In contrast, VT-x provides separate operating modes for the guest and VMM. Another difference from VT-x is that ARM does not automatically save and restore architectural state when switching between a VMM and a guest. Instead, the VMM is expected to manage state in software, perhaps creating an opportunity for optimization.

最近,各种非 x86 硬件平台获得了对硬件辅助虚拟化的支持,包括 ARM[38]、Intel Itanium[25]和 IBM Power[24]。ARM 尤其令人感兴趣,因为它在移动设备中非常流行,这使得 ARM 虚拟化扩展成为 Dune 未来的明显目标。Arm 对虚拟化的支持在某些方面与 VT-x 类似。例如,ARM 能够公开对特权硬件功能的直接访问,包括异常、虚拟内存和特权模式。此外,ARM 提供了与 EPT 相当的系统 MMU。ARM 最显著的区别是它引入了一种新的更深的特权模式,称为 HYP,它在客户内核下运行。相反,VT-x 为客户和 VMM 提供单独的操作模式。与 VT-x 的另一个不同之处在于,当在 VMM 和客户操作系统之间切换时,ARM 不会自动保存和恢复架构状态。相反,VMM 被期望管理软件中的状态,这可能为优化创造了机会。

8 相关工作 Related Work

There have been several efforts to give applications greater access to hardware. For example, The Exokernel [18] exposes hardware features through a low-level kernel interface that allows applications to manage hardware resources directly. Another approach, adopted by the SPIN project [7], is to permit applications to safely load extensions directly into the kernel. Dune shares many similarities with these approaches because it also tries to give applications greater access to hardware. However, Dune differs because its goal is not extensibility. Rather, Dune provides access to privileged hardware features so that they can be used in concert with the OS instead of as a means of modifying or overriding it.

已经做出了一些努力来使应用程序能够更好地访问硬件。例如,ExoKernel[18]通过允许应用程序直接管理硬件资源的低级内核接口公开硬件功能。SPIN 项目[7]采用的另一种方法是允许应用程序安全地将扩展直接加载到内核中。Dune 与这些方法有许多相似之处,因为它也试图让应用程序更多地访问硬件。然而,Dune 有所不同,因为它的目标不是可扩展性。相反,Dune 提供对特权硬件功能的访问,以便它们可以与操作系统协同使用,而不是作为修改或覆盖它的手段。

The Fluke project [20] supports a nested process model in software, allowing OSes to be constructed “vertically.” Dune complements this approach because it could be used to efficiently support an extra OS layer between the application and the kernel through the use of privilege mode hardware. However, the hardware that Dune exposes can only support a single level instead of the multiple levels available in Fluke.

Fluke 项目[20]支持软件中的嵌套进程模型,允许操作系统 “纵向 “构建。Dune 补充了这种方法,因为它可以通过使用特权模式硬件来有效地支持应用程序和内核之间的额外操作系统层。然而,Dune 所公开的硬件只能支持一个层次,而不是 Fluke 中的多个层次。