Andrew W. Appel and Kai Li

Department of Computer Scienece, Princeton University

摘要 Abstract

Memory Management Units (MMUs) are traditionally used by operating systems to implement disk-paged virtual memory. Some operating systems allow user programs to specify the protection level (inaccessible, read-only, read-write) of pages and allow user programs to handle protection violations, but these mechanisms are not always robust, efficient, or well-matched to the needs of applications.

传统上,操作系统使用内存管理单元(MMU)来实现磁盘分页虚拟内存。一些操作系统允许用户指定页的保护等级(不可访问、只读、可读写),并且允许用户程序来处理非法操作,但是这些机制并不总是健壮、有效或符合应用程序需求的。

We survey several user-level algorithms that make use of page-protection techniques, and analyze their common characteristics, in an attempt to answer the question, “What virtual-memory primitives should the operating system provide to the user process, and how well do today’s operating systems provide them?”

我们调查了几种页保护技术的用户态算法,并且分析了它们的共同点,以回答这样一个问题:“操作系统应该为用户提供什么样的虚拟内存原语,现今的操作系统又在何种程度上提供了?”

1. 介绍 Introduction

The “traditional” purpose of virtual memory is to increase the size of the address space visible to user programs, by allowing only the frequently-accessed subset of the address space to be resident in physical memory. But virtual memory has been used for many other purposes. Operating systems can share pages between processes, make instruction spaces read-only (and thus guarantee re-entrant), make portions of memory zeroed-on-demand or copy-on-write, and so on [18]. In fact, there is a large class of “tricks” that operating systems can perform using page protection hardware.

虚拟内存的“传统”目的是通过只允许将经常访问的内存保存在物理内存上来拓展程序员可见的地址空间。但是虚拟内存也被用于很多其他目的。操作系统可以用虚拟内存来在不同的进程之间共享页,可以让指令空间只读(从而保证可以重复执行),让部分内存实现按需归零或写时复制,等等。事实上,操作系统可以把页保护硬件玩出很多花样。

Modern operating systems allow user programs to perform such tricks too, by allowing user programs to provide “handlers” for protection violations. Unix, for example, allows a user process to specify that a particular subroutine is to be executed whenever a segmentation-fault signal is generated. When a program accesses memory beyond its legal virtual address range, a user-friendly error message can be produced by the user-provided signal handler, instead of the ominous “segmentation fault: core dumped.”

同样,现代操作系统也通过让用户进程为非法操作提供“处理程序”来让用户也能使用此类技巧。以Unix为例,当出现段错误信号时,用户可以指定一个子例程来处理。当一个程序访问内存越界时,用户提供的信号处理程序可以给出一条用户友好的错误信息,而不是不详的 “segmentation fault: core dumped.”

This simple example of a user-mode fault handler is “dangerous”, because it may lead the operating system and hardware designers to belives that user-mode handlers need not be entered efficiently (which is certainly the case for the “graceful error shutdown” example). But there are many more interesting applications of user-mode fault handlers. These applications exercise the page-protection and fault handling mechanisms quite strenuously and should be understood by operating system implementors.

这个简单的用户态错误处理程序是“危险的”,因为它可能导致操作系统和硬件设计者认为不需要高效地使用用户态处理程序(在“优雅地关闭错误”这一示例中肯定是这样的)。但是,用户态错误处理程序还有很多有趣的应用。这些应用程序非常严格地执行页保护和错误处理机制,操作系统的实现者应该理解这些机制。

This paper describes several algorithms that make use of page-protection techniques. In many cases, the algorithms can substitute the use of “conventional” paging hardware for the “special” microcode that has sometimes been used. On shared-memory multiprocessors, the algorithms use page-protection hardware to achieve medium-grained synchronization with low overhead, to avoid synchronization instruction sequences that have noticeable overhead.

本文介绍了几种页保护技术的算法。在许多情况下,这些算法能够用“传统”的页硬件来代替“特殊”的微指令。在共享内存的多核处理器上,这些算法利用页保护硬件来实现低开销中等粒度的同步,以避免开销较大的同步序列化指令。

2. 虚拟内存原语 Virtual memory primitives

Each of the algorithms we will describe requires some of the following virtual-memory services from the operating system:

我们描述的每种算法都需要操作系统提供以下的虚拟内存访问:

TRAP: handle page-fault traps in user mode; 在用户态处理页错误陷阱

PROT1: decrease the accessibility of a page; 降低一页的访问权限

PROTN: decrease the accessibility of N page; 降低N页的访问权限

UNPROT: increase the accessibility of a page; 提高一页的访问权限

DIRTY: return a list of dirtied pages since the previous call; 返回自上次调用以来的脏页列表

MAP2: map the same physical page at two different virtual addresses, at different levels of protection, in the same address space. 在同一个地址空间中以不同的保护级别将两个不同的虚拟地址映射到相同的物理页。

Finally, some algorithms may be more efficient with a smaller PAGESIZE than is normally used with disk paging.

最后,与常用的磁盘页相比,某些算法的页更小、更高效。

We distinguish between “decreasing the accessibility of a page” and “decreasing the accessibility of a batch of pages” for a specific reason. The cost of changing the protection of several pages simultaneously maybe not much more than the cost of changing the protection of one page. Several of the algorithms we describe protect pages (make them less accessible) only in large batches. Thus, if an operating system implementation could not efficiently decrease the accessibility of a large batch at a small cost-per-page, this would suffice for some algorithms.

由于特定原因,我们区分了“降低单页的访问权限”和“降低多页的访问权限”。同时更改多页的保护权限的成本不比改变单页高多少。我们描述的一些算法只能降低多页的访问权限。因此,如果操作系统的实现不能让保护单页的成本比保护多页的成本低很多,那么这对某些算法来说就足够了。

We do not make such a distinction for unprotecting single vs multiple pages because none of the algorithms we describe ever unprotect many pages simultaneously.

我们不对取消保护单页和多页进行这样的区分,因为我们描述的算法都不会同时取消保护多页。

Some multi-thread algorithms require that one thread have access to a particular page of memory while others fault on the page. There are many solutions to such a problem (as will be described later), but one simple and efficient solution is to map the page into more than one virtual address: at one address the page is accessible and at the other address its faults. For efficiency reasons, the two different virtual addresses should be in the same page table, so that expensive page-table context switching is not required between threads.

一些多线程算法要求同一个页面可以允许某个线程访问,同时禁止其他线程访问。对于这一的问题,有很多解决方案(后面会介绍),但一个简单而有效的解决方案是将页映射到多个虚拟内存地址:一个虚拟内存地址是可访问的;而另一个虚拟内存是不可访问的。出于效率考虑,这两个不同的虚拟内存地址应该在同一个页表中,这一就不需要在线程之间进行昂贵的页表的上下文切换。

The user program can keep track of dirty pages using PROTN, TRAP, and UNPROT; we list DIRTY as a separate primitive because it may be more efficient for the operating system to provide this service directly.

用户程序可以使用PROTN、TRAP和UNPROT来追踪脏页;我们将DIRTY列为单独的原语,因为操作系统直接提供此服务可能更有效。

3. 虚拟内存的应用 Virtual memory applications

We present in this section a sample of applications which use virtual-memorty primitives in place of software tests, special hardware, or microcode. The page protection hardware can efficiently test simple predicates on addresses that might otherwise require one or two extra instructions on every fetch and/or store; this is a substantial savings, since fetches and stores are very common operations indeed. We survey several algorihms so that we may attempt to draw gerneral conclusions about what user programs require from the operating system and hardware.

在本节中,我们将介绍一个使用虚拟内存原语来代替用软件检测、特殊硬件或微码的应用程序示例。页保护硬件可以对地址进行简单而有效地验证,否则每次获取和/或存储都需要一条或两条额外的指令;这是一个巨大的节约,因为存取确实是非常常见的操作。我们调查了几种算法,以便就用户程序对操作系统和硬件的要求得出一般结论。

并行垃圾回收 Concurrent garbage collection

A concurrent, real-time, copying garbage collection algorithm can use the page fault mechanism to achieve medium-grain synchronization between collector and mutator threads [4]. The paging mechanism provides synchronization that is coarse enough to be efficient and yet fine enough to make the latency low. The algorithm is based on Baker’s sequential, real-time copying collector algorithm [6].

并行、实时、复制的垃圾回收算法可以使用页错误机制来实现垃圾收集器和mutator之间的中粒度同步[4]。分页机制提供同步的粒度在效率和低延迟之间达到了平衡。该算法是基于Baker的顺序实时复制垃圾回收算法。

Baker’s algorithm divides the memory heap into two regions, from-space and to-space. At the beginning of a collection, all objects are in from-space, and to-space is empty. Starting with the registers and other global roots, the collector traces out the graph of objects reachable from the roots, copying each reachable object into to-space. A pointer to an object from-space is forwarded by making it point to the to-space copy of the old object. Of course, some from-space objects are never copied into to-space, because no pointer to them is ever forwarded; these objects are garbage.

Baker算法将内存堆区分为两个区域:源空间和目标空间。在垃圾回收开始时,所有对象都在源空间,目标空间是空的。从寄存器和全局根开始,垃圾回收器沿指针找到对象,将每个找到的对象复制到目标空间。指向源空间对象的指针将转而指向目标空间中原来对象的副本(“转发”)。当然,有些源空间中的对象永远不会被复制到目标空间,因为没有指向他们的指针,这些对象是垃圾。

As soon as the registers are forwarded, the mutator thread can resume execution. Reachable objects are copied incrementally from-space while the mutator allocates new objects at new. Every time the mutator allocates a new object, it invokes the collector to copy a few more objects from from-space. Baker’s algorithm maintains the following invariants:

在寄存器被转发后,mutator就可以恢复执行。当mutator使用new来分配新对象时,源空间中的可访问对象被复制。每当mutator分配一些新对象,它就会调用收集器从源空间中复制一些对象。Baker算法保持了以下不变性:

The mutator sees only to-space pointers in its registers.

mutator在寄存器中只能看到目标空间的指针

Objects in the new area contain to-space pointers only (because new objects are initialized from the registers).

新区域中的对象只包含目标空间的指针(因为新对象是从寄存器初始化的)

Objects in the scanned area contain to-space pointers only.

扫描空间中的对象只包含目标空间的指针

Objects in the unscanned area contain bot from-space and to-space pointers.

未扫描空间中的对象包含源空间和目标空间的指针

To satisfy the invariant that the mutator sees only to-space pointers in its registers, every pointer fetched from an object must be checked to see if it points to from-space. If it does, the from-space object is copied to to-space and the pointer updated; only then is the pointer returned to the mutator. This checking requires hardware support to be implemented efficiently [25] since otherwise a few extra instructions must be performed on every fetch. Furthermore, the mutator and the collector must alternate; they cannot operate truly concurrently because they might simultaneously try to copy the same object to different places.

为了满足不变性,既mutator只能在寄存器中看到目标空间的指针,每个对象里的指针都要被检查,看它是否指向源空间。如果是的话,源空间的对象就会被复制到目标空间,并更新指针;只有这样,指针才会返回给mutator。这种检查需要硬件支持来有效地实现[25],否则每次都要执行一些额外的指令。此外,mutator和垃圾回收器必须交替执行;它们不能真正地并发操作,因为它们可能同时试图将一个对象复制到不同的地方。

Instead of checking every pointer fetched from memory, the concurrent collector [4] uses virtual-memory page protections to detect from-space memory references and to synchronize the collector and mutator threads. To synchronize the mutators and collectors, the algorithm sets the virtual-memory protection of the unscanned area’s pages to be “no access.” Whenever the mutator tries to access an unscanned object, it will get a page-access trap. The collector fields the trap and scans the objects on that page, copying from-space objects and forwarding pointers as necessary. Then it unprotects the page and resumes the mutator at the faulting instruction. To the mutator, that page appears to have contained only to-space pointers all along, and thus the mutator will fetch only to-space pointers to its registers.

并行垃圾回收器并不检查从内存中获取的每个指针,而是使用虚拟内存的页保护来检测对源空间的非法引用[4],并让收集器和mutator同步。为了同步收集器和mutator,该算法将未扫描区的虚拟内存页保护设置为“禁止访问”。每当mutator试图访问一个未扫描的对象时,就会触发一个页访问陷阱。收集器处理该陷阱并扫描该页上的对象,复制源空间的对象并在必要时转发指针。然后,它解除该页的保护,并从出错的指令处恢复mutator的运行。对于mutator来说,该页似乎一直都只包含目标空间的指针,因此mutator只能获取目标空间的指针到其寄存器。

The collector also executes concurrently with the mutator, scanning pages in the unscanned area and unprotecting them as each is scanned. The more pages scanned concurrently, the fewer page-access traps taken by the mutator. Because the mutator doesn’t do anything extra to synchronize with the collector, compilers needn’t be reworked. Multiple processors and mutator threads are accommodated with almost no extra effort.

收集器也和mutator并行执行,扫描未扫描区的页,并在每个页被扫描时解除其保护。同时扫描的页越多,mutator引发的页访问陷阱越少。因为mutator没有做任何额外的事情来和收集器同步,所以编译器不需要重做。几乎不需要额外的努力,就可以支持多个处理器和mutator。

This algorithm requires TRAP, PROTN, UNPROT, and MAP2. Traps are required to detect fetches from the unscanned area; protection of multiple pages is required to mark the entire to-space inaccessible when the flip is done; UNPROT is required as each page is scanned. In addition, since the time for the user-mode handler to process the page is proportional to page size, it may be appropriate to use a small PAGESIZE to reduce latency.

此算法需要TRAP、PROTN、UNPROT和MAP2。需要陷阱来检测对为扫描区域的读取;需要保护多页以在翻转完成时将整个目标空间标记为不可访问。在每个页面被扫描时需要UNPROT。此外,由于用户态处理程序处理页面的时间与页面大小成正比,因此可以用较小的PAGESIZE来减少延迟。

We need multiple mapping of the same page so that the garbage collector can scan a page while it is still inaccessible to the mutators. Alternatives to multiple mapping are discussed in section 5.

我们需要对同一个页面进行多次映射,这样垃圾收集器就可以在一个页面还不能被mutator访问的时候扫描它。第五节将讨论多重映射的替代方案。

共享虚拟内存 Share virtual memory

The access protection paging mechanism has been used to implement shared virtual memory on a network of computers, on a multicomputer without shared memories [21], and on a multiprocessor based on interconnection networks [14]. The essential idea of shared virtual memory is to use the paging mechanism to control and maintain single-writer and multiple-reader coherence at the page level.

访问保护分页机制已用于在计算机网络上、在没有共享内存的多计算机上[21]以及基于互连网络的多处理器[14]上实现共享虚拟内存。共享虚拟内存的基本思路是使用分页机制来控制和维护页面级的单个写入器和多个读取器的一致性。

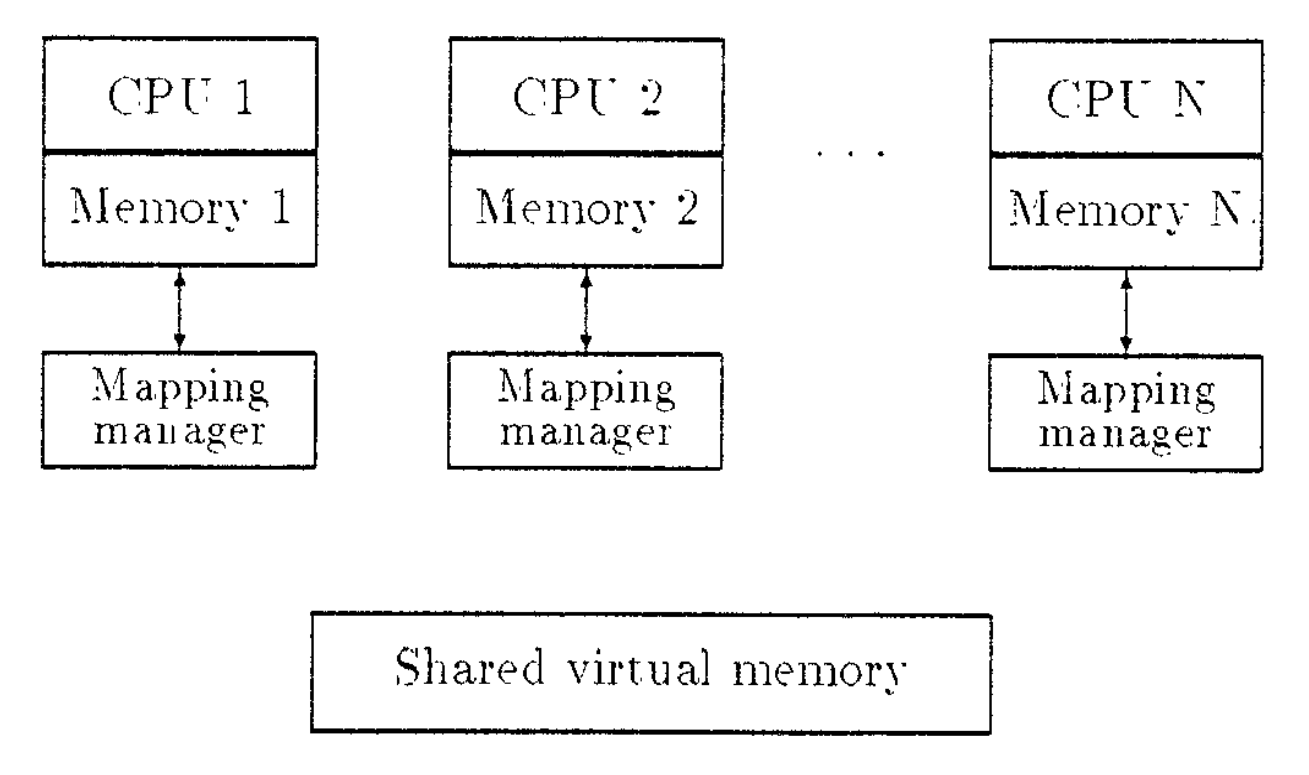

Figure 1 shows the system architecture of an SVM system. On a multicomputer, each node in the system consists of a processor and its memory. The nodes are connected by a fast message-passing network.

图1显示了SVM系统的系统架构。在多计算机上,系统中的每个节点都由一个处理器及其内存组成。节点通过快速消息传递网络连接。

Figure 1: Shared virtual memory

The SVM system presents all processors with a large coherent shared memory address space. Any processor can access any memory location at any time. The shared memory address space can be as large as the memory address space provided by the MMU of the processor. The address space is coherent at all times, that is, the value returned by a read operation is always the same as the value written by the most recent write operation to the same address.

SVM系统向所有处理器呈现一个大的一致共享存储器地址空间。任何处理器都可以在任何时间访问任何内存位置。共享内存地址空间可以与处理器的MMU提供的内存地址空间一样大。地址空间始终是一致的。也就是说,读操作返回的值始终与最近一次写操作写入同一地址的值相同。

The SVM address space is partitioned into pages. Pages that are marked “read-only” can have copies residing in the physical memories of many processors at the same time. But a page currently being written can reside in only one processor’s physical memory. If a processor wants to write a page that is currently residing on other processors, it must get an up-to-date copy of the page and then tel] the other processors to invalidate their copies. The memory mapping manager views its local memory as a big cache of the SVM address space for its associated processors. Like the traditional virtual memory [15], the shared memory itself exists only virtually. A memory reference may cause a page fault when the page containing the memory location is not in a processor’s current physical memory. When this happens, the memory mapping manager retrieves the page from either disk or the memory of another processor.

SVM地址空间被划分为多个页面。被标记为 “只读 “的页可以有副本同时驻留在许多处理器的物理内存中。但当前正被写入的页可仅驻留在一个处理器的物理内存中。如果处理器想要写入当前驻留在其他处理器上的页面,它必须获取页面的最新副本,然后告诉其他处理器使其副本失效。内存映射管理器将其本地内存视为其关联处理器的SVM地址空间的一个大缓存。与传统的虚拟内存[15]一样,共享内存本身也是虚拟的。当包含内存位置的页面不在处理器当前的物理内存中时,内存引用可能导致页错误。当这种情况发生时,内存映射管理器会从磁盘或另一个处理器的内存中检索该页。

This algorithm uses TRAP, PROT1, and UNPROT: the trap-handler needs access to memory that is still protected from the client threads (MAP2), and a small PAGESIZE may be appropriate.

这种算法使用TRAP、PROT1和UNPROT:陷阱处理程序需要访问仍然受客户线程保护的内存(MAP2),较小的PAGESIZE可能是合适的。

并发检查 Concurrent checkpointing

The access protection page fault mechanism has been used successfully in making checkpointing concurrent and real-time [22]. This algorithm for shared-memory multiprocessors runs concurrently with the target program and interrupts the target program for small fixed amounts of time and is transparent to the checkpointed program and its compiler. The algorithm achieves its efficiency by using the paging mechanism to allow the most time-consuming operations of the checkpoint to be overlapped with the running of the program being checkpointed.

访问保护页面故障机制已成功用于实现并发和实时检查[22]。这种用于共享存储器多处理器的算法与目标程序同时运行,并在固定的短时间内中断目标程序,并且对检查程序及其编译器是透明的。该算法通过使用分页机制以允许检查的最耗时操作与被检查的程序的运行重叠,从而提高其效率。

First, all threads in the program being checkpointed are stopped. Next, the writable main memory space for the program is saved (including the heap, globals, and the stacks for the individual threads.) Also, enough state information is saved for each thread so that it can be restarted. Finally, the threads are restarted.

首先,停止被设置检查点的程序中的所有线程。接下来,保存程序的可写主内存空间(包括堆、全局变量和各个线程的堆栈)。此外,还为每个线程保存了足够的状态信息,以便可以重新启动它。最后。线程将重新启动。

Instead of saving the writable main memory space to disk all at once, the algorithm avoids this long wait by using the access protection page fault mechanism. First, the accessibility of the entire address space is set to “read-only.” At this point, the threads of the checkpointed program are restarted and a copying thread sequentially scans the address space, copying the pages to separate virtual address space as it goes. When the copying thread finishes copying a page, it sets its access rights to “read/write.”

该算法通过使用访问保护页面故障机制来避免这种长时间的等待,而不是一次将可写主存空间全部保存到磁盘。首先,将整个地址空间的可访问性设置为只读。此时,检查程序的线程重新启动,复制线程顺序扫描地址空间,将页面复制到单独的虚拟地址空间。当复制线程完成页面复制时,它将其访问权限设置为“读/写”。

When the user threads can make read memory references to the read-only pages, they run as fast as with no checkpointing. If a thread of the program writes a page before it has been copied, a write memory access fault, will occur. At this point, the copying thread immediately copies the page and sets the access for the page to “read/write,” and restarts the faulting thread.

当用户线程可以对只读页进行读取内存引用时,它们的运行速度与没有检查点时一样快。如果程序线程在页被复制之前写入页,则将发生写内存访问错误。此时,复制线程立即复制该页,并将该页的访问设置为“读/写”,然后重新启动故障线程。

Several benchmark programs have been used to measure the performance of this algorithm on the DEC Firefly multiprocessors [33]. The measurements show that about 90% of the checkpoint work is executed concurrently with the target program while no thread is ever interrupted for more than 1 second at a time.

几个基准程序已用于测量该算法在DEC Firefly多处理器上的性能[33]。测量结果表明,大约90%的检查工作是与目标程序并发执行的,而任何线程都不会一次中断超过1秒。

This method also applies to taking incremental checkpoints; saving the pages that have been changed since the last checkpoint. Instead of protecting all the pages with “read-only,” the algorithm can protect only “dirtied” pages from the previous checkpoint. Feldman and Brown [17] implemented and measured a sequential version for a debugging system by using reversible executions. They proposed and implemented the system call DIRTY.

此方法也适用于获取增量检查点;保存自上次检查点以来已更改的页。该算法不是用“只读”保护所有页面,而是只保护来自前一个检查点的“脏”页面。Feldman和Brown[17]通过使用可逆执行实现并测量了调试系统的顺序版本。他们提出并实现了DIRTY系统调用。

This algorithm uses TRAP, PROT1, PROTN, UNPROT, and DIRTY; a medium PAGESIZE may be appropriate.

这个算法使用TRAP、PROT1、PROTN、UNPROT和DIRTY;中等大小的页面可能比较合适。

分代垃圾收集 Generational garbage collection

An important application of memory protection is in generational garbage collection[23], a very efficient algorithm that depends on two properties of dynamically allocated records in LISP and other programming languages:

内存保护的一个重要应用是分代垃圾收集[23],这是一种非常有效的算法,它依赖于LISP和其他编程语言中动态分配记录的两个属性:

Younger records are much more likely to die soon than older records. If a record has already survived for a long time, it’s likely to survive well into the future: a new record is likely to be part of a temporary, intermediate value of a calculation.

新记录比老记录更有可能很快死亡。如果一条记录已经存在了很长一段时间,那么它很可能会在未来很长一段时间内继续存在:新记录很可能是计算的临时中间值的一部分。

Younger records tend to point to older records since in LISP and functional programming languages they act, of allocating a record also initializes it to point to already-existing records.

新记录往往指向老记录,因为在Lisp和函数式编程语言中,它们在分配记录时也会将其初始化为指向已经存在的记录。

Property 1 indicates that much of the garbage collector’s effort should be concentrated on younger records, and property 2 provides a way to achieve this. Allocated records will be kept in several distinct areas Gi of memory, called generations. Records in the same generation are of similar age, and all the records in generation Gi are older than the records in generation Gi+1. By observation 2 above, for i < j, there should be very few or no pointers from Gi into Gj. The collector will usually collect in the youngest generation, which has the highest proportion of garbage. To perform a collection in a generation, the collector needs to know about all pointers in the generation; these pointers can be in machine registers, in global variables, and on the stack. However, there are very few such pointers in older generations because of property 2 above.

属性1表明,垃圾收集器的大部分工作应集中在新记录上,而属性2提供了实现这一点的方法。分配的记录将保存在内存的几个不同的区域Gi中,称为代。同一代中的记录具有相似的年龄,并且代Gi中的所有记录都比世代Gi+1中的记录更老。通过以上的观察,对于i<j,应该有很少或没有从Gi到Gj的指针。收集者通常会在最新的一代收集垃圾,这一代的垃圾比例最高。要在代中执行收集,收集器需要知道代中的所有指针。这些指针可以在机器寄存器、全局变量和堆栈中。然而,由于上面的属性2,在老一代中很少有这样的指针。

The only way that an older generation can point to a younger one is by an assignment to an already-existing record. To detect such assignments, each modification of a heap object must be examined to see whether it violates property 2. This checking can be done by special hardware [25,35], or by compilers [34]. In the latter case, two or more instructions are required. Fortunately, non-initializing assignments are rare in Lisp, Smalltalk, and similar languages [25,35,30,3] but the overhead of the instruction sequence for checking (without special hardware) is still on the order of 5-10% of total execution time.

老一代可以指向新一代的唯一方法是分配到已经存在的记录。为了检测这样的赋值,必须检查对堆对象的每个修改,以查看它是否违反了属性2。这种检查可以通过特殊硬件[25,35]或编译器[34]来完成。在后一种情况下,需要两个或多个指令。幸运的是,非初始化赋值在Lisp、Smalltalk和类似语言[25,35,30,3]中很少出现,但用于检查的指令序列的开销(无特殊硬件)仍占总执行时间的5-10%。

Virtual memory hardware can detect assignments to old objects. If DIRTY is available, the collector can examine dirtied pages to derive pointers from older generations to younger generations and process them. In the absence of such a service, the collector can use the page protection mechanism [30]: the older generations can be write-protected so that any store into them will cause a trap. The user trap-handler can save the address of the trapping page on a list for the garbage collector; then the page must be unprotected to allow the store instruction to proceed. At garbage-collection time the collector will need to scan the pages on the trap list for possible pointers to the youngest generation. Variants of this algorithm have exhibited quite good performance [30,11]: as heaps and memories get larger this scheme begins to dominate other techniques[37].

虚拟内存硬件可以检测对旧对象的分配。如果DIRTY可用,则收集器可以检查已脏的页,以获取从较老的页到较新的页的指针,并处理这些指针。在没有这种服务的情况下,收集器可以使用页保护机制[30]:较老的几代可以被写保护,这样任何存储到其中的内容都会引起陷阱。用户陷阱处理程序可以将陷阱页面的地址保存在垃圾收集器的列表上。然后该页必须解除保护以允许存储指令继续进行。在垃圾收集时,收集器需要扫描陷阱列表上的页面,以查找指向最新一代的可能指针。该算法的变体表现出相当好的性能[30,11]:随着堆和存储器变得更大,该方案开始压倒其他技术[37]。

This technique uses the TRAP, PROTN, and UNPROT features, or just DIRTY. In addition, since the time for the user-mode handler to process the page is independent of page size, and the eventual time for the garbage collector to scan the page is proportional to the page size, it may be appropriate to use a small PAGESIZE.

这种技术使用TRAP、PROTN和UNPROT特性,或者只使用DIRTY。此外,由于用户模式处理程序处理页面的时间与页面大小无关,而垃圾收集器扫描页面的最终时间与页面大小成正比,所以使用一个小的PAGESIZE可能是合适的。

持久存储 Persistent stores

A persistent store [5] is a dynamic allocation heap that persists from one program invocation to the next. Execution of a program may traverse data structures in the persistent store just as it would in its own (in-core) heap. It may modify objects in the persistent store, even to make them point to newly-allocated objects of its own; it may then commit these modifications to the persistent store, or it may abort, in which case, there is no net effect on the persistent store. Between (and during) executions, the persistent store is kept on a stable storage device such as a disk so that the “database” does not disappear.

持久存储[5]是一种动态分配堆,它从一个程序调用持续到下一个程序调用。程序的执行可以遍历持久存储中的数据结构,就像它在自己的(核内)堆中一样。它可以修改持久存储中的对象,甚至使它们指向它自己新分配的对象;然后,它可以将这些修改提交给持久存储,或者它可以中止,在这种情况下,对持久存储没有净影响。在两次执行之间(以及执行期间),持久存储保存在稳定的存储设备(如磁盘)上,这样 “数据库 “就不会消失。

Traversals of pointers in the persistent store must be just, as fast as fetches and stores in main memory; ideally, data structures in the persistent store should not be distinguishable by the compiled code of a program from data structures in the core. This can be accomplished through the use of virtual memory: the persistent store is a memory-mapped disk file; pointer traversal through the persistent store is Just the same as pointer traversal in the core, with page faults if new parts of the store are examined.

持久存储中的指针遍历必须与主内存中的读取和存储一样快;理想情况下,程序的编译代码不应将持久存储中的数据结构与内核中的数据结构区分开来。这可以通过虚拟内存来实现:持久存储是内存映射磁盘文件;持久存储的指针遍历与内核中的指针遍历相同,如果检查到存储的新部分,则会出现页错误。

However, when an object in the persistent store is modified, the permanent image must not be altered until the commit. The in-core image is modified, and only at the commit are the “dirty” pages (possibly including some newly-created pages) written back to the disk. To reduce the number of new pages, it is appropriate to do a garbage collection at commit time.

但是,当修改持久存储中的对象时,在提交之前不得更改永久镜像。修改内核镜像,并且只有在提交时才将“脏”页(可能包括一些新创建的页)写回磁盘。为了减少新页的数量,可以在提交时进行垃圾回收。

A database is a storage management system that may provide, among other things, locking of objects, transactions with abort/commit, checkpointing, and recovery. The integration of virtual memory techniques into database implementations has long been studied [24,31].

数据库是一种存储管理系统,其可以提供对象的锁定、具有能够中止/提交的事务、检查点设置和恢复等。长期以来,人们一直在研究将虚拟内存技术集成到数据库实现中[24,31]。

Compiled programs can traverse the data in their heaps very quickly and easily, since each access operation is just a compiled fetch instruction. Traversal of data in a conventional database is much slower since each operation is done by a procedure call; the access procedures ensure synchronization and affordability of transactions. Persistent stores can be augmented to cleanly handle concurrency and locking: such systems (sometimes called object-oriented databases) can be quickly traversed with fetch instructions but also can provide synchronization and locking: efficiency of access can be improved by using a garbage collector to group related objects on the same page, treat small objects differently than large objects, and so on[13].

编译后的程序可以非常快速、轻松地遍历堆中的数据,因为每个访问操作只是一个编译后的获取指令。传统数据库中数据的遍历要慢得多,因为每个操作都是由过程调用完成的;访问程序确保事务的同步性和可承受性。可以扩展持久存储以干净地处理并发和锁定:这样的系统(有时称为面向对象的数据库)可以使用获取指令快速遍历,而且还可以提供同步和锁定:可以通过使用垃圾收集器在同一页面上对相关对象进行分组来提高访问效率,将小对象与大对象区别对待,等等[13]。

These schemes require the use of TRAP and UNPROT as well as file-mapping with copy-on-write (which, if not otherwise available, can be simulated using PROTN, UNPROT, and MAP2.

这些方案需要使用TRAP和UNPROT以及带写时复制的文件映射(如果没有其他方法,可以用PROTN、UNPROT和MAP2来模拟。

扩展寻址能力 Extending addressability

A persistent store might grow so large that it contains more than (for example) 2^32 objects, so that it cannot be addressed by 32-bit pointers. Modern disk drives (especially optical disks) can certainly hold such large databases, but conventional processors use 32-bit addresses. However, in any one run of a program against the persistent store, fewer than 2^32 objects will likely be accessed.

持久性存储可能会变得非常大,以至于它包含的对象超过(例如)2^32个,因此无法通过32位指针进行寻址。现代磁盘驱动器(尤其是光盘)当然可以容纳如此大的数据库,但传统处理器使用32位地址。然而,在任何一次针对持久性存储的程序运行中,被访问的对象可能少于2^32个。

One solution to this problem is to modify the persistent store mechanism so that objects in the core use 32-bit addresses and objects on disk use 64-bit addresses. Each disk page is exactly twice as long as a core page. When a page is brought from disk to core, its 64-bit disk pointers are translated to 32-bit core pointers using a translation table. When one of these 32-bit core pointers is dereferenced for the first, time, a page fault may occur; the fault handler brings in another page from the disk, translating it to short, pointers.

这个问题的一个解决方案是修改持久存储机制,以便核心中的对象使用32位地址,而磁盘上的对象使用64位地址。每个磁盘页的长度正好是核心页的两倍。当页从磁盘进入内核时,使用转换表将64位磁盘指针转换为32位核心指针。当这些32位核心指针中的一个首次被取消引用时,可能发生页错误;错误处理程序从磁盘引入另一个页面,将其转换为短指针。

The translation table has entries only for those objects accessed in a single execution: that is why 32-bit pointers will suffice. Pointers in the core may point to not yet-accessed pages; such a page is not allocated in the core, but there is an entry in the translation table showing what (64-bit pointer) disk page holds its untranslated contents.

转换表只有那些在单次执行中访问的对象的条目:这就是为什么32位指针就足够了。核心中的指针可以指向尚未访问的页面;这样的页面不在核心中分配,但在转换表中有一个条目,显示哪个(64位指针)磁盘页面保存其未转换的内容。

The idea of having short pointers in core and long pointers on disk, with a translation table for only that subset, of objects used in one session, originated in the LOOM system of Smalltalk-80 [20]. The use of a page fault mechanism to implement it is more recent [19]. This algorithm uses TRAP, UNPROT, PROT1, or PROTN, and (in a multi-threaded environment) MAP2, and might work well with a smaller PAGESIZE.

核心中有短指针,磁盘上有长指针,一个会话中使用的对象的子集只有一个转换表,这个想法起源于Smalltalk-80[20]的LOOM系统。最近使用页错误机制来实现它[19]。此算法使用TRAP、UNPROT、PROT1或PROTN以及(在多线程环境中)MAP2,并且可能适用于较小的页面大小。

数据压缩分页 Data-compression paging

In a typical linked data structure, many words point to nearby objects; many words are nil. Those words that contain integers instead of pointers often contain small integers or zero. In short, the information-theoretic entropy of the average word is small: furthermore, a garbage collector can be made to put objects that point to each other in nearby locations, thus reducing the entropy per word to as little as 7 bits[9].

在典型的链接数据结构中,许多字指向附近的对象;许多字都是零。那些包含整数而不是指针的字通常包含小整数或零。简而言之,平均字的信息熵很小:此外,可以让垃圾收集器将指向彼此的对象放在附近的位置,从而将每个字的熵减少到7位[9]。

By the use of a data-compression algorithm, then, a page of 32-bit words might be compressible to about one-quarter of a page. Instead of paging less-recently used pages directly to the disk, they could be compressed instead and put back into the main memory.[36] Then, when those virtual pages are again needed, it might take much less time to uncompress them than it would fetch from the disk. Of course, compressed pages could be sent out to disk after a long period of disuse.

然后,通过使用数据压缩算法,32位字的页可以被压缩到大约四分之一页。与其将不太常用的页面分到磁盘上,不如将其压缩后放回主内存中。[36]然后,当再次需要这些虚拟页时,解压缩它们所花费的时间可能比从磁盘获取它们所花费的时间要少得多。当然,压缩后的页面可以在长期不用后发送到磁盘。

Of course, data-compression paging might be done inside the operating system transparently to the user process[28]. But since a garbage collector can move objects to minimize their entropy, much better results might be obtained if the user process can have some control over how and when compression is done.

当然,数据压缩分页可以在操作系统内部完成,对用户进程透明[28]。。但是,由于垃圾收集器可以移动对象以使其熵最小化,如果用户进程可以对如何以及何时进行压缩进行一些控制,则可以获得更好的结果。

This algorithm requires TRAP, PROT1 (or perhaps PROTN with careful buffering), and UNPROT. It is necessary to determine when pages are not recently used: this can be done by occasionally protecting pages to see if they are referenced, or with help from the operating system and hardware.

此算法需要TRAP、PROT1(或者可能是经过仔细缓冲的PROTN)和PROPT。有必要确定哪些页面最近没有被使用:这可以通过偶尔保护页面以查看它们是否被引用来完成,或者在操作系统和硬件的帮助下完成。

堆溢出检测 Heap overflow detection

The stack of a process or thread requires protections against overflow accesses. A well-known and practical technique used in most systems is to mark the pages above the top of the stack as invalid or with no access. Any memory access to these pages will cause a page fault. The operating system can catch such a fault and inform the user program of a stack overflow. In most implementations of Unix, stack pages are not allocated until first used; the operating system’s response to a page fault is to allocate physical pages, mark them accessible, and resume execution without notifying the user process (unless a resource limit is exceeded).

进程或线程的堆栈需要针对溢出访问的保护。在大多数系统中使用的一种众所周知且实用的技术是将堆栈顶部以上的页面标记为无效或不可访问。对这些页面的任何内存访问都将导致页错误。操作系统可以捕获这样的错误,并通知用户程序堆栈溢出。在大多数UNIX实现中,堆栈页只有在第一次使用时才会分配。操作系统对页错误的响应是分配物理页面,将其标记为可访问,并在不通知用户进程的情况下恢复执行(除非超出资源限制)。

This technique requires TRAP, PROTN, and UNPROT. But since the faults are quite rare (most processes don’t use much stack space), efficiency is not a concern.

这种技术需要TRAP、PROTN和UNPROT。但由于错误是相当罕见的(大多数进程不会使用太多的堆栈空间),所以效率并不是一个问题。

The same technique can be used to detect heap overflow in a garbage-collected system[2]. Ordinarily, heap overflow in such a system is detected by a compare and conditional branch performed on each memory allocation. By having the user process allocate new records in a region of memory terminated by a guard page, the compare and conditional branches can be eliminated.

相同的技术可用于检测垃圾收集系统中的堆溢出[2]。通常情况下,在这样的系统中,堆溢出是通过对每个内存分配进行比较和条件分支来检测的。通过让用户进程在由保护页终止的内存区域中分配新记录,可以消除比较分支和条件分支。

When the end of the allocatable memory is reached, a page-fault trap invokes the garbage collector. It can often be arranged that no re-arrangement of memory protection is required since after the collection the same allocation area can be re-used. Thus, this technique requires PROT1 and TRAP.

当到达可分配内存的末尾时,页错误陷阱将调用垃圾收集器。通常可以安排不需要重新安排内存保护,因为在收集之后,可以重新使用相同的分配区域。因此,该技术需要PROT1和TRAP。

Here, the efficiency of TRAP is a concern. Some language implementations allocate a new cell as frequently as every 50 instructions. In a generational garbage collector, the size of the allocation region may be quite small to make the youngest generation fit entirely in the data cache; a 64 Kbyte allocation region could hold 16 Kbyte list cells, for example. In a very-frequently allocating system (e.g. one that keeps activation records on the heap), such a tiny proportion of the data will be live that the garbage-collection time itself will be small. Thus, we have:

这里,陷阱的效率是一个值得关注的问题。一些语言实现分配新单元的频率为每50条指令。在分代垃圾收集器中,分配区域的大小可能非常小,以使最新的代完全适合于数据高速缓存;例如,64kb分配区域可以保存16K字节的列表单元。在非常频繁的分配系统(例如,在堆上保存激活记录的系统)中,数据的极小部分将是活动的,因此垃圾收集时间本身也将很短。因此,我们有:

Instructions executed before heap overflow:

堆溢出前执行的指令。

(64k /8) x 50 = 400k.

Instructions of overhead, using compare and branch:

使用比较和分支的开销指令。

(64k /8) x 2 = 16k.

If a trap takes 1200 cycles to handle (as is typical— see section 4), then this technique reduces the overhead from 4% to 0.8%, worthwhile savings. If a trap were to take much longer, this technique would not be as efficient.

如果一个陷阱需要1200个周期来处理(典型的情况——见第4节),那么这种技术可以将开销从4%降低到0.8%,这是值得的。如果陷阱需要更长的时间,这种技术就不会那么有效。

Since there are other good techniques for reducing heap-limit-check overhead, such as combining the hit checks for several consecutive allocations in an unrolled loop, this application of virtual memory is perhaps the least interesting of those discussed in this paper.

由于有其他好的技术可以减少堆限制检查开销,例如在展开的循环中合并几个连续分配的命中检查,因此这种虚拟内存的应用可能是本文中讨论的应用中最不有趣的。

4 虚拟内存原语性能 VM primitive performance

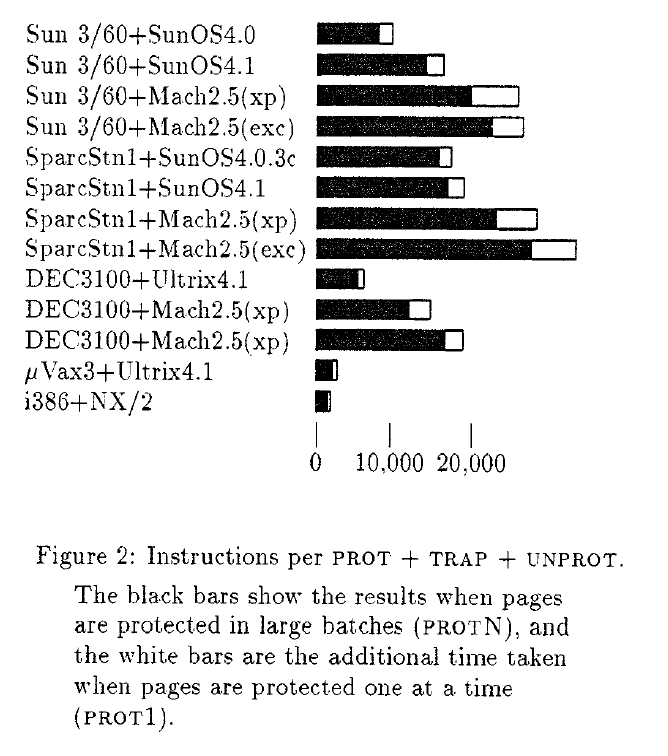

Almost all the algorithms we described in this paper fall into one of the two categories. The first category of algorithms protects pages in large batches, then upon each page-fault trap, they unprotect one page. The second category of algorithms protects a page and unprotects a page individually. Since PROTN or PROT, TRAP, and UNPROT are always used together, an operating system in which one of the operations is extremely efficient, but others are very slow will not be very competitive.

我们在本文中描述的几乎所有算法都属于以下两类中的一类:第一类算法是大批量地保护页面,然后在每个页故障陷阱时,取消保护一个页面;第二类算法分别保护取消保护页面。由于PROTN或PROT、TRAP和PROPT总是一起使用,因此如果一个操作系统的其中一个操作非常高效,而其他操作非常慢,那么它就不会有很强的竞争力。

We performed two measurements for overall user mode virtual-memory performance. The first is the sum of PROT1, TRAP, and UNPROT, as measured by 100 repetitions of the following benchmark program:

我们对整体用户模式虚拟内存性能进行了两项测量。第一个是PROT1、TRAP和UNPROT的总和,通过100次重复下面的基准程序进行测量:

access a random protected page, and

访问一个随机的受保护页面,并且

in the fault-handler, protect some other page and unprotect the faulting page.

在故障处理程序中,保护其他一些页面并取消对故障页面的保护。

This process is repeated 100 times to obtain more accurate timing.

此过程重复100次以获得更准确的计时。

The second measurement is the sum of PROTN, TRAP, and UNPROT. The benchmark program measures:

第二个测量值是PROTN、TRAP和UNPROT的总和。基准程序测量:

protect 100 pages,

保护100页,

access each page in a random sequence, and

以随机顺序访问每个页面,以及

in the fault-handler, unprotect the faulting page. Before beginning the timing, both programs write each page to eliminate the transient effects of filling the cache and TLB.

在故障处理程序中,解除对故障页的保护。在开始计时之前,两个程序都会写入每个页面,以消除填充高速缓存和TLB的瞬时效应。

We compared the performance of Ultrix, SunOS, and Mach on several platforms in the execution of these benchmarks. For calibration, we also show the time for a single instruction (ADD), measured using a 20 instruction loop containing 18 adds, as a comparison, and a branch. Where we have the data, we also show the time for a trap-handler that does not change any memory protections: this would be useful for heap-overflow detection. The results are shown in Table 1. Note that this benchmark is not an “overall operating system throughput” benchmark [27] and should not be influenced by disk speeds: it is measuring the performance of CPU-handled virtual memory services for user-level programs.

在执行这些基准测试时,我们比较了Ultrix、SunOS和Mach在几个平台上的性能。为了校准,我们还显示了使用包含18个加法的20条指令循环测量的单个指令(加法)的时间,作为比较和分支。在我们有数据的地方,我们还显示了不改变任何内存保护状态的陷阱处理程序的时间:这对于堆溢出检测非常有用。结果如表1所示。请注意,此基准测试不是“整体操作系统吞吐量”基准测试[27],并且不应受到磁盘速度的影响:它是为用户级程序测量CPU处理的虚拟内存服务的性能。

We also tried mapping a physical page at two different virtual addresses in the same process, using the shared memory operations (shmop) on SunOS and Ultrix, and on Mach using vm_emap. SunOS and Mach permit this, but Ultrix would not permit us to attach (short) the same shared-memory object at two different addresses in the same process.

我们还尝试在SunOS和Ultrix上使用共享内存操作(shmop),在Mach上使用vm_map,在同一进程中的两个不同虚拟地址映射同一个物理页面。SunOS和Mach允许这样做,但Ultrix不允许我们在同一进程中的两个不同地址附加(shmat)同一共享内存对象。

There are wide variations in the performance of these operating systems even on the same hardware. This indicates that there may be considerable room for improvement in some or all of these systems. Furthermore, several versions of operating systems do not correctly flush their translation buffer after an mprotect call, indicating that many operating systems implementors don’t take this feature seriously.

即使在相同的硬件上,这些操作系统的性能也有很大的差异。这表明这些系统中的一些或全部可能有相当大的改进空间。此外,多个版本的操作系统在mprotect调用后无法正确刷新其转换缓冲区,这表明许多操作系统实现者并不重视此功能。

These operating system services must be made efficient. The argument here is much more specific than a vacuous “Efficiency is good.” For disk paging, a page fault usually implies a 20-millisecond wait for the disk to spin around to the right sector:

必须提高这些操作系统服务的效率。这里的论点比空洞的“效率就是好”要具体得多。“对于磁盘分页,一个页错误通常意味着需要等待20毫秒的时间让磁盘旋转到正确的扇区:

| Machine | OS | ADD | TRAP | TRAP+PROT1+UNPROT | TRAP+PROTN+UNPROT | MAP2 | PAGESIZE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun 3/60 | SunOS 4.0 | 0.12 | 760 | 1238 | 1016 | yes | 8192 |

| Sun 3/60 | SunOS 4.1 | 0.12 | 760 | 2080 | 1800 | yes | 8192 |

| Sun 3/60 | Mach 2.5(xp) | 0.12 | 760 | 3300 | 2540 | yes | 8192 |

| Sun 3/60 | Mach 2.5(exc) | 0.12 | 760 | 3380 | 2880 | yes | 8192 |

| SparcStn 1 | SunOS 4.0.3c | 0.05 | 230 | 919 | 839 | yes | 4096 |

| SparcStn 1 | SunOS 4.1 | 0.05 | 230 | 1008 | 909 | yes | 4096 |

| SparcStn 1 | Mach 2.5(xp) | 0.05 | 230 | 1550 | 1230 | yes | 4096 |

| SparcStn 1 | Mach 2.5(exc) | 0.05 | 230 | 1770 | 1470 | yes | 4096 |

| DEC 3100 | Ultrix 4.1 | 0.062 | 210 | 393 | 344 | no | 4096 |

| DEC 3100 | Mach 2.5(xp) | 0.062 | 210 | 937 | 766 | no | 4096 |

| DEC 3100 | Mach 2.5(exc) | 0.062 | 210 | 1203 | 1063 | no | 4096 |

| uVax3 | Ultrix 2.3 | 0.21 | 314 | 612 | 486 | no | 1024 |

| i386 on iPSC/2 | NX/2 | 0.15 | 172 | 302 | 252 | yes | 4096 |

so a 3 or 5-millisecond fault handling overhead would be hardly noticed as a contributor to fault-handling latency. But in the algorithms surveyed in the paper, the fault will be handled entirely within the CPU. For example, we have implemented a garbage collector that executes about 10 instructions per word of to-space. For page size of 4096 bytes (1024 words) on a 20 MIPS machine, the computation time to handle a fault will be approximately 10*0.05*1024 or about 500 microseconds. If the operating system’s fault-handling and page-protection overhead are 1200 microseconds (as is average), then the operating system is the bottleneck.

因此,3或5毫秒的错误处理开销几乎不会被认为是处理延迟的原因。但在本文研究的算法中,错误将完全在CPU内处理。例如,我们已经实现了一个垃圾收集器,它在每个目标空间的字中执行大约10条指令。对于20 MIPS机器上4096字节(1024字)的页面大小,处理错误的计算时间约为10*0.05*1024或约500微秒。如果操作系统的错误处理和页面保护开销为1200微秒(平均值),则操作系统是瓶颈。

If the program exhibits a good locality of reference, then the garbage-collection faults will be few, and the operating system overhead will matter less. But for real-time programs, which must satisfy strict constraints on latency, even an occasional “slow fault” will cause problems. For example, if the client program must never be interrupted for more than a millisecond, then a fault-handler computation time of 500 microseconds doesn’t leave room for an operating system overhead of 1200 microseconds! (This issue gets more complicated when we consider multiple consecutive faults; see [11] for an analysis.)

如果程序表现出良好的引用局部性,那么垃圾收集错误就会很少,操作系统开销也就不那么重要。但对于实时程序来说,必须满足严格的延迟限制,即使是偶尔的“慢错误”也会导致问题。例如,如果客户端程序的中断时间绝不能超过一毫秒,那么500微秒的错误处理程序计算时间就不能为1200微秒的操作系统开销留出余地!(当我们考虑多个连续错误时,这个问题变得更加复杂;有关分析,请参见[11]。)

To compare virtual memory primitives on different architectures, we have normalized the measurements by processor speed. Figure 2 shows the number of ADDs each processor could have done in the time it takes to protect a page, fault, and unprotect a page.

为了比较不同架构上的虚拟内存原语,我们通过处理器速度对测量结果进行了标准化。图2显示了每个处理器在保护页面、错误和取消保护页面所需的时间内可以完成的ADD指令数量。

Our benchmark shows that there is a wide range of efficiency in implementing virtual memory primitives. Intel 80386-based machine running NX/2 operating system [29] (a simple operating system for the iPSC/2 hypercube multicomputer) is the best m our benchmark. Its normalized benchmark performance is about ten times better than the worst performer (Mach on the Sparcstation). Clearly, there is no inherent reason that these primitives must be slow. Hardware and operating system designers should treat memory-protection performance as one of the important tradeoffs in the design process.

我们的基准测试表明,实现虚拟内存原语的效率范围很广。运行NX/2操作系统[29](用于iPSC/2超立方体多计算机的简单操作系统)的基于Intel 80386的机器是我们的基准中最好的。它的标准化基准测试性能比性能最差的(Sparcstation上的Mach)好十倍左右。显然,这些原语没有必然缓慢的内在原因。硬件和操作系统设计人员应将内存保护性能视为设计过程中的重要权衡因素之一。

5 系统设计问题 System design issues

We can learn some important lessons about hardware and operating system design from our survey of virtual memory applications. Most of the applications use virtual memory in similar ways: this makes it clear what VM support is needed – and just as important, what is unnecessary.

从我们对虚拟内存应用程序的调查中,我们可以学到一些关于硬件和操作系统设计的重要经验。大多数应用程序都以类似的方式使用虚拟内存:这清楚地表明了需要哪些虚拟内存支持——同样重要的是,哪些是不必要的。

TLB一致性 TLB Consistency

Many of the algorithms presented here make their memory less accessible in large batches, and make the memory more accessible one page at a time. This is true of concurrent garbage collection, generational garbage collection, concurrent checkpointing, persistent store, and extending addressability.

这里介绍的许多算法使它们的内存在大量访问中不那么容易被访问,而使内存一次一页的访问中更容易访问。并发垃圾收集、分代垃圾收集、并发检查、持久存储和扩展寻址能力都是如此。

This is a good thing, especially on a multiprocessor, because of the translation lookaside buffer (TLB) consistency problem. When a page is made more accessible, outdated information in TLBs is harmless, leading to at most a spurious, easily patchable TLB miss or TLB fault. But when a page is made less accessible, outdated information in TLBs can lead to illegal access to the page. To prevent this, it is necessary to flush the page from each TLB where it might reside. This “shootdown” can be done in software by interrupting each of the other processors and requesting it to flush the page from its TLB, or in hardware by various bus-based schemes[7,32].

这是一件好事,特别是在多处理器上,因为存在转换后备缓冲区(TLB)一致性问题。当页变得更容易访问时,TLB中的过时信息是无害的,最多会导致虚假的、容易修补的TLB未命中或TLB故障。但是,当页的可访问性降低时,TLB中的过时信息可能会导致对该页的非法访问。为了防止这一点,有必要从它可能驻留的每个TLB中刷新该页。这种“关闭”可以在软件中通过中断每个其他处理器并请求它从其TLB中刷新页面来完成,或者在硬件中通过各种基于总线的方案来完成[7,32]。

Software shootdown can be very expensive if there are many processors to interrupt. Our solution to the shootdown problem is to batch the shootdowns; the cost of a (software) shootdown covering many pages simultaneously is not much greater than the cost of a single-page shootdown: the cost per page becomes negligible when the overhead (of interrupting the processers to notify them about shootdowns) is amortized over many pages. The algorithms described in this paper that protect pages in batches “inadvertently” take advantage of the batched shootdown.

如果有许多处理器要中断,则软件关闭可能非常昂贵。我们对关闭问题的解决方案是批量关闭。同时覆盖多个页的(软件)关闭的成本并不比单页关闭的成本高多少:当开销(中断处理器以通知它们关闭)分摊到多个页面时,每页的成本变得可以忽略不计。本文中描述的批量保护页面的算法“无意中”利用了批量关闭。

Batching suggested itself to us because of the structure of the algorithms described here, but it can also solve the shootdown problem for “traditional” disk paging. Pages are made less accessible in disk paging (they are “paged out’) to free physical pages for re-use by other virtual pages. If the operating system can maintain a large reserve of unused physical pages, then it can do its paging-out in batches (to replenish the reserve); this will amortize the shootdown cost over the entire batch. Thus, while it has been claimed that software solutions work reasonably well but might need to be supplanted with hardware assist [7], with batching, likely, the hardware would not be necessary.

由于这里描述的算法的结构,我们想到了批处理,但它也可以解决“传统”磁盘页的问题。在磁盘页中,页面的可访问性较低(它们被“换出”),以释放物理页面供其他虚拟页重用。如果操作系统可以维护大量未使用的物理页储备,那么它可以批量进行页面调出(以补充储备)。这将在整个批次中分摊关闭成本。因此,虽然有人声称软件解决方案工作得相当好,但可能需要用硬件辅助[7]取代,但在批处理的情况下,硬件可能不是必需的。

最佳页面大小 Optimal page size

In many of the algorithms described here, page faults are handled entirely in the CPU, and the fault-handling time (exclusive of overhead) is a small constant time the page size.

在这里描述的许多算法中,页面错误完全在CPU中处理,并且错误处理时间(不包括开销)是一个很小的常数乘以页大小。

When a page fault occurs for paging between physical memories and disks, there is a delay of tens of milliseconds while the disk rotates and the head moves. A computational overhead of a few milliseconds in the page fault handler will hardly be noticed (especially if there are no other processes ready to execute). For this reason—and many others, including the addressing characteristics of dynamic RAMs—pages have traditionally been quite large, and fault-handling overhead has been high.

当物理内存和磁盘之间的分页发生页错误时,在磁盘旋转和磁头移动时会有几十毫秒的延迟。页面错误处理程序中几毫秒的计算开销几乎不会被注意到(特别是在没有其他进程准备执行的情况下)。由于这个原因(以及许多其他原因,包括动态RAM的寻址特性),页通常相当大,并且错误处理开销也很高。

For user-handled faults that are processed entirely by user algorithms in the CPU, however, there is no such inherent latency. To halve the time of each fault (exclusive of trap time), it suffices to halve the page size. The various algorithms described here might perform best at different page sizes.

然而,对于完全由CPU中的用户算法处理的错误,不存在这种固有的延迟。要将每个故障的时间减半(不包括陷阱时间),将页大小减半就足够了。这里描述的各种算法可能在不同的页大小上表现最佳。

The effect of a varying page size can be accomplished on hardware with small page size. (In the VMP system, the translation buffer and the cache are the same things, with a 128-byte line size [8]: this architecture might be well-suited to many of the algorithms described in this paper.) For PROT and UNPROT operations, the small pages would be used; for disk paging, contiguous multi-page blocks would be used (as is now common on the Vax).

改变页面大小的效果可以在页较小的硬件上实现。(在VMP系统中,转换缓冲区和高速缓存是相同的东西,具有128字节的行大小[8]:这种架构可能非常适合本文中描述的许多算法。)对于PROT和UNPROT操作,将使用小页面;对于磁盘分页,将使用连续的多页块(现在在Vax上很常见)。

When small pages are used, it is particularly important to trap and change page protections quickly, since this overhead is independent, of page size while the actual computation (typically) takes time proportional to page size.

当使用小页面时,快速捕获和更改页面保护尤为重要,因为此开销与页大小无关,而实际计算(通常)花费的时间与页大小成比例。

访问受保护的页面 Access to protected pages

Many algorithms, when run on a multiprocessor, need a way for a user-mode service routine to access a page while client threads have no access. These algorithms are concurrent garbage collection, extending addressability, shared virtual memory, and data-compression paging.

当在多处理器上运行时,许多算法需要一种用户态服务程序在客户线程无法访问页面时访问页面的方法。这些算法包括并发垃圾收集、扩展寻址能力、共享虚拟内存和数据压缩分页。

There are several ways to achieve user-mode access to protected pages (we use the concurrent garbage collection algorithm to illustrate):

有几种方法可以实现用户态对受保护页面的访问(我们用并发的垃圾收集算法来说明):

Multiple mapping of the same page at different addresses (and at different levels of protection) in the same address space. The garbage collector has access to pages In to-space at a “nonstandard” address, while the mutators see to-space as protected.

同一页在同一地址空间中的不同地址(以及不同保护级别)上的多重映射。垃圾收集器可以访问“非标准”地址的目标空间中的页面,而mutator将目标空间视为受保护的。

A system call could be provided to copy memory to and from a protected area. The collector would use this call three times for each page: once when copying records from from-space to to-space; once before scanning the page of to-space: and once just after scanning, before making the page accessible to the mutators. This solution is less desirable because it is not very efficient to do all that copying.

可以提供系统调用来将内存复制到受保护区域和从受保护区域复制内存。收集器将对每个页面使用此调用三次:一次是在将记录从源空间复制到目标空间时;一次是在扫描目标空间的页面之前,一次是在扫描之后,在使页面可供mutator访问之前。这种解决方案是不太理想的,因为它不是非常有效地进行所有的复制。

In an operating system that permits shared pages between processes, the collector can run in a different, the heavyweight process from the mutator, with a different page table. The problem with this technique is that it requires two expensive heavyweight context switches on each garbage-collection page trap. However, on a multiprocessor, it may suffice to do an RPC to another processor that’s already in the right context, and this option might be much more attractive.

在允许进程之间共享页的操作系统中,收集器可以在不同重量级的进程中运行,该进程与mutator具有不同的页表。这种技术的问题在于,它需要在每个垃圾收集页陷阱上进行两次昂贵的重量级上下文切换。然而,在多处理器上,对已经在正确上下文中的另一个处理器执行RPC可能就足够了,这个选项可能更有吸引力。

The garbage collector can run inside the operating system kernel. This is probably the most efficient, but perhaps that’s not the appropriate place for a garbage collector; it can lead to unreliable kernels, and every programming language has a different runtime data format that the garbage collector must understand.

垃圾收集器可以在操作系统内核中运行。这可能是最有效的,但可能不是垃圾收集器的合适位置。它可能导致内核不可靠,并且每种编程语言的垃圾收集器必须理解的不同的运行时数据格式。

We advocate that for computer architectures with physically addressed caches, the multiple virtual address mapping in the same address space is a clean and efficient solution. It does not require heavyweight context switches, data structure copies, or running things in the kernel. There is the small disadvantage that each physical page will require two different entries in the page tables, increasing physical memory requirements by up to 1%, depending on the ratio of page-table-entry size to page size.

我们主张,对于具有物理地址缓存的计算机架构,同一地址空间中的多个虚拟地址映射是一种干净高效的解决方案。它不需要重量级的上下文切换、数据结构复制或在内核中运行。有一个小缺点,即每个物理页面将需要页表中两个不同的条目,从而使物理内存需求增加多达1%,具体取决于页表条目大小与页面大小的比率。

With a virtually-addressed cache, the multiple virtual address mapping approach has a potential for cache inconsistency since updates at one mapping may reside in the cache while the other mapping contains stale data. This problem is easily solved in the context of the concurrent garbage-collection algorithm. While the garbage collector is scanning the page, the mutator has no access to the page; therefore at the mutator’s address for that page, none of the cache lines will be filled. After the collector has scanned the page, it should flush its cache lines for that page (presumably using a cache flush system call). Thereafter, the collector will never reference that page, so there is never any danger of inconsistency.

对于虚拟地址的高速缓存,多个虚拟地址映射方法具有高速缓存不一致的可能性,因为一个映射处的更新可能驻留在高速缓存中,而另一个映射包含旧数据。这个问题在并发垃圾收集算法中很容易解决。当垃圾收集器扫描页面时,mutator不能访问页面;因此,对于mutator来说,不会填充任何的高速缓存行。在收集器扫描了页之后,它应该刷新该页的缓存行(假设使用缓存刷新系统调用)。此后,收集器将永远不会引用该页面,因此永远不会有任何不一致的危险。

这要求是不是太高了? Is this too much to ask?

Some implementations of Unix on some machines have had a particularly clean and synchronous signal handling facility: an instruction that causes a page fault invokes a signal handler without otherwise changing the state of the processor; subsequent instructions do not execute, etc. The signal handler can access machine registers completely synchronously, change the memory map or machine registers, and then restart the faulting instruction. However, on a highly pipelined machine, there may be several outstanding page faults [26], and many instructions after the faulting one may have written their results to registers even before the fault is noticed; instructions can be resumed, but not restarted. When user programs rely on synchronous behavior, it is difficult to get them to run on pipelined machines: Modern UNIX systems … let user programs actively participate in memory management functions by allowing them to explicitly manipulate their memory mappings. This… serves as the courier of an engraved invitation to Hell[26].

UNIX在某些机器上的某些实现具有特别干净和同步的信号处理功能:导致页错误的指令调用信号处理程序,而不会改变处理器的状态。后续指令不执行等。信号处理程序可以完全同步地访问机器寄存器,更改内存映射或机器寄存器,然后重新启动出错指令。然而,在高度流水线化的机器上,可能有几个未解决的页面错误[26],并且在错误之后的许多指令可能甚至在注意到错误之前就已经将其结果写入寄存器;指令可以恢复,但不能重新启动。当用户程序依赖于同步行为时,很难让它们在流水线机器上运行:现代UNIX系统..通过允许用户程序显式地操作其内存映射,让用户程序主动参与内存管理功能。这..成了派送地狱邀请函的信使[26]。

If the algorithms described are indeed incompatible with fast, pipelined machines, it would be a serious problem. Fortunately, all but one of the algorithms we described are sufficiently asynchronous. Their behavior is to fix the faulting page and resume execution, without examining the CPU state at the time of the fault. Other instructions that may have begun or been completed are, of course, independent of the contents of the faulting page. The behavior of these algorithms, from the machine’s point of view, is very much like the behavior of a traditional disk-pager: get a fault, provide the physical page, make the page accessible in the page table, and resume.

如果所描述的算法确实与快速的流水线机器不兼容,这将是一个严重的问题。幸运的是,我们描述的所有算法都是足够异步的。它们的行为是修复发生错误的页面并恢复执行,而不检查发生错误时的CPU状态。当然,可能已经开始或完成的其他指令与错误页的内容无关。从机器的角度来看,这些算法的行为非常类似于传统磁盘寻址器的行为:获取错误,提供物理页,使页在页表中可访问,然后恢复。

The exception to this generalization is heap overflow detection: a fault initiates a garbage collection that execution. The register containing the pointer to the next allocatable word is adjusted to point to the beginning of the allocation space. The previously faulting instruction is re-executed, but this time it won’t fault because it’s stored in a different location.

这种泛化的例外是堆溢出检测:错误会启动执行的垃圾收集。包含指向下一个可分配字的指针的寄存器被调整为指向分配空间的开始。重新执行以前的出错指令,但这次它不会出错,因为它存储在不同的位置。

| Methods | TRAP | PROT1 | PROTN | UNPROT | MAP2 | DIRTY | PAGESIZE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concurrent GC | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| SVM | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Concurrent checkpoint | √ | √ | √ | ++ | √ | ||

| Generational GC | √ | √ | √ | ++ | √ | ||

| Persistent store | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Extending addressability | √ | * | * | √ | √ | √ | |

| Data-compression paging | √ | * | * | √ | √ | ||

| Heap overflow | √ | + |

Table 2: Usages of virtual memory system services

The behavior is unacceptable on a highly-pipelined machine (unless, as on the VAX 8800 [10], there is hardware for “undoing” those subsequent instructions or addressing-mode side-effects that have already been completed). Even on the Motorola 68020, the use of page faults to detect heap overflow is not reliable.

这种行为在高度流水线化的机器上是不可接受的(除非像VAX 8800[10]那样,有硬件来“撤销”那些已经完成的后续指令或寻址模式的副作用)。即使在Motorola 68020上,使用页错误来检测堆溢出也不可靠。

Thus, except for heap overflow detection, all of the algorithms we present pose no more problem for the hardware than does ordinary disk paging, and the invitation to Hell can be returned to sender: however, the operating system must make sure to provide adequate support for what the hardware is capable of: semi-synchronous trap-handlers should resume faulting operations correctly.

因此,除了堆溢出检测之外,我们提出的所有算法都不会给硬件带来比普通磁盘分页更多的问题,并且可以将地狱邀请函退回给发送者:但是,操作系统必须确保为硬件的能力提供足够的支持:半同步陷阱处理程序应该正确地恢复错误操作。

其他原语 Other primitives

Other virtual memory primitives operating systems can provide. For a persistent store with transactions, it might be useful to pin a page[16] in core so that it is not written back to the backing store until the transaction is complete.

操作系统可以提供其他虚拟内存原语。对于具有事务的持久存储,将页[16]固定在核心中可能是有用的,以便在事务完成之前不会将其写回后备存储。

The Mach external-pager interface[1] provides at least one facility which is lacking from the primitives we describe: the operating system can tell the client which pages are least-recently-used and (therefore) about to be paged out. The client might choose to destroy those pages rather than have them written to disk. This would be particularly useful for data-compression paging and extending addressability. Also, in a system with garbage collection, the client might know that a certain region contains only garbage and can safely be destroved[12].

Mach外部分页器接口[1]至少提供了一种我们所描述的原语所缺少的功能:操作系统可以告诉客户哪些页面是最近最少使用的,(因此)即将被换出。客户端可能会选择销毁这些页面,而不是将它们写入磁盘。这对于数据压缩、分页和扩展寻址能力特别有用。此外,在具有垃圾收集的系统中,客户端可能知道某个区域只包含垃圾,并且可以安全地销毁[12]。

In general, the external-pager interface avoids the problem in general of the operating-system pager (which writes not-recently-used pages to disk) needlessly duplicating the work that the user-mode fault handler is also doing.

通常,外部分页器接口避免了操作系统分页器(将最近未使用的页面写入磁盘)不必要地重复用户态错误处理程序也在进行的工作的问题。

6 结论 Conclusions

Where virtual memory was once just a tool for implementing large address spaces and protecting one user process from another, it has evolved into a user-level component of hardware and operating-system interface. We have survived several algorithms that rely on virtual memory primitives; such primitives have not been paid enough attention in the past. In designing and analyzing the performance of new machines and new operating systems, page protection and fault handling efficiency must be considered as one of the parameters of the design space; page size is another important parameter. Conversely, for many algorithms, the configuration of TLB hardware (e.g. on a multiprocessor) may not be particularly important.

虚拟内存曾经只是实现大地址空间和保护一个用户进程不受另一个用户进程影响的工具,它已经发展成为硬件和操作系统接口的用户级组件。我们已经通过了几个依赖于虚拟内存原语的算法。这样的原语在过去没有得到足够的重视。在设计和分析新机器和新操作系统的性能时,页保护和错误处理效率必须作为设计空间的参数之一加以考虑。页面大小是另一个重要参数。相反,对于许多算法,TLB硬件的配置(例如,在多处理器上)可能不是特别重要。

Table 2 shows the usages and requirements of these algorithms. Some algorithms protect pages one at a time (PROT1), while others protect pages in large batches (PROTN), which is easier to implement efficiently. Some algorithms require access to protected pages when run concurrently (MAP2), Some algorithms use memory protection only to keep track of modified pages (DIRTY), a service that could perhaps be provided more efficiently as a primitive. Some algorithms might run more efficiently using a smaller page size than is commonly used (PAGESIZE).

表2显示了这些算法的用法和要求。有些算法是一次保护一个页面(PROT1),而有些算法是大批量保护页面(PROTN),后者更容易高效实现。一些算法在并发运行时需要访问受保护的页面(MAP2),一些算法仅使用内存保护来跟踪修改的页面(DIRTY),该服务可能可以作为原语更有效地提供。某些算法使用比通常使用的页大小(PAGESIZE)更小的页面大小可能会运行得更高效。

Many algorithms that make use of virtual memory share several traits:

许多利用虚拟内存的算法都有以下几个特点:

Memory is made less accessible in large batches, and made more accessible one page at a time; this has important implications for TLB consistency algorithms.

内存在大批量访问中的可访问性较低,而在一次访问一个页面中的可访问性较高;这对TLB一致性算法有重要影响。

The fault-handling is done almost entirely by the CPU, and takes time proportional to the size of a page (with a relatively small constant of proportionality); this has implications for preferred page size.

故障处理几乎完全由CPU完成,所需时间与页的大小成正比(比例常数相对较小);这对页大小有影响。

Every page fault results in the faulting page being made more accessible.

每一个页错误都会导致错误页变得更容易访问。

The frequency of faults is inversely related to the locality of reference of the client program: this will keep these algorithms competitive in the long run.

错误的频率与客户程序的引用位置成反比:从长远来看,这将保持这些算法的竞争力。

User-mode service routines need to access pages that are protected from user-mode client routines.

用户态服务程序需要访问不让用户态客户程序访问的页面。

User-mode service routines don’t need to examine the client’s CPU state.

用户态服务程序不需要检查客户的CPU状态。

All the algorithms described in the paper (except heap overflow detection) share five or more of these characteristics.

本文所描述的所有算法(除堆溢出检测外)都具有上述五个或更多的特点。

Most programs access only a small proportion of their address space during a medium-size period. This is what makes traditional disk paging efficient; in different ways, it makes the algorithms described here efficient as well. For example, the concurrent garbage collection algorithm must scan and copy the same amount of data regardless of the mutator’s access pattern [4], but the mutator’s locality of reference reduces the fault handling overhead. The “write barrier” in the generational collection algorithm, concurrent checkpointing, and persistent store algorithms take advantage of locality if some small subset of objects accounts for most of the updates. And the shared virtual memory algorithms take advantage of a special kind of partitioned locality of reference, in which each processor has a different local reference pattern.

在中等大小的时间段内,大多数程序只访问其地址空间的一小部分。这就是传统磁盘分页效率高的原因。以不同的方式,它使得这里描述的算法也是有效的。例如,无论mutator的访问模式如何,并发垃圾收集算法都必须扫描和复制相同数量的数据[4],但mutator的引用局部性减少了错误处理开销。分代收集算法、并发检查点和持久存储算法中的“写屏障”利用了局部性(如果对象的某个小子集占据了大部分更新)。并且共享虚拟内存算法利用了一种特殊的分区引用局部性,其中每个处理器具有不同的局部引用模式。

We believe that, because these algorithms depend so much on the locality of reference, they will scale well. As memories get larger and computers get faster, programs will tend to actively use an even smaller proportion of their address space, and the overhead of these algorithms will continue to decrease. Hardware and operating system designers must make the virtual memory mechanisms required by these algorithms robust, and efficient.

我们相信,因为这些算法非常依赖于引用的局部性,所以它们可以很好地扩展。随着内存变得越来越大,计算机变得越来越快,程序将倾向于主动使用更小比例的地址空间,并且这些算法的开销将继续减少。硬件和操作系统设计者必须使这些算法所需的虚拟内存机制健壮且高效。

鸣谢 Acknowledgements

Thanks to Rick Rashid, David Tarditi, and Greg Morrisett for porting various versions of our benchmark program to Mach and running it on Mach machines, and Larry Rogers for running it on SunOS. Rafael Alonso, Brian Bershad, Chris Clifton, Adam Dingle, Marv Fernandez, John Reppy, and Carl Staelin made helpful suggestions on early drafts of the paper.

感谢Rick Rashid, David Tarditi和Greg Morrisett将我们不同版本的基准程序移植到Mach上并在Mach机器上运行,感谢Larry Rogers让基准程序在SunOS上运行。Rafael Alonso, Brian Bershad, Chris Clifton, Adam Dingle, Marv Fernandez, John Reppy, 和Carl Staelin对本文的早期草稿提出了有益的建议。

Andrew W. Appel was supported in part by NSF Grant CCR-8806121. Kai Li was supported in part by NSF Grant CCR-8814265 and by Intel Supercomputer Systems Division.

Andrew W. Appel得到了美国国家科学基金会CCR-8806121拨款的部分支持。Kai Li得到了美国国家科学基金会CCR-8814265拨款和英特尔超级计算机系统部门的部分支持。

参考文献 References

[1] Mike Accetta, Robert Baron. William Bolosky. David Golub, Richard Rashid, Avadis Tevanian, and Michael Young. Mach: A new kernel foundation for UNIX development. In Proc. Summer Usenix, July 1986.

[2] Andrew W. Appel. Garbage collection can be faster than stack allocation. Information Processing Letters, 25(4):275-279, 1987.

[3] Andrew W. Appel. Simple generational garbage collection and fast allocation. Software—Practice/Experience, 19(2):171183, 1989.

[4] Andrew W. Appel. John R. Ellis, and Kai Li. Real-time concurrent collection on stock multiprocessors. S/JGPLAN Notices (Proc. SIGPLAN ‘88 Conf. on Prog. Lang. Design and Implementation). 23(7):11-20, 1988.

[5] Malcolm Atkinson, Ken Chisholm. Paul Cockshott, and Richard Marshall. Algorithms for a persistent heap. Software—Practice and Experience, 13(3):259271, 1983.

[6] H. G. Baker. List processing in real-time on a serial computer. Communications of the ACM, 21(4):280294, 1978.

[7] David L. Black, Richard F. Rashid. David B. Golub, Charles R. Hill, and Robert V. Brown. ‘Translation lookaside buffer consistency: A software approach. In Proc. 3rd Int’l Conf. on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, pages 113-122. 1989.

[8] David R. Cheriton. The vmp multiprocessor: Initial experience, refinements, and performance evaluation. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Symposium on Computer Architecture, 1988.

[9] D. W. Clark and C. C. Green. An empirical study of list structure in Lisp. IEEE Trans. Software Eng., SE5(1):51-59, 1977.

[10] Douglas W. Clark. Pipelining and performance in the VAX 8800 processor. In Proc. 2nd Intl. Conf. Architectural Support for Prog. Lang. and Operating Systems. pages 173-179, 1987.

[11] Brian Cook. Four garbage collectors for Oberon. Undergraduate thesis, Princeton University. 1989.

[12] Eric Cooper. personal communication, 1990.

[13] George Copeland, Michael Franklin, and Gerhard Weikum. Uniform object management. In Advances in Database Technology—EDBT ’90, pages 253-268. opringerVerlag, 1990.

[14] A.L. Cox and R.J. Fowler. The implementation of a coherent memory abstraction on a numa multiprocessor: Experiences with platinum. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Symposium on Operating Systems Principles. pages 32-44, December 1989.

[15] Peter J. Denning. Working sets past and present. [EEE Trans. Software Engineering, SE-6(1):64-84, 1980.

[16] Jeffrey L. Eppinger. Virtual Memory Management for Transaction Processing Systems. Ph.D. thesis, Carnegie Mellon University. February 1989.

[17] S. Feldman and C. Brown. Igor: A system for program debugging via reversible execution. ACM SIGPLAN Notices, Workshop on Parallel and Distributed Debugging, 24(1):112-123, January 1989.

[18] R. Fitzgerald and R.F. Rashid. The integration of virtual memory management and interprocess communication in accent. 4CM Transactions on Computer Systems, 4(2):147-177, May 1986.

[19] Ralph Johnson and Paul R. Wilson. personal communication, 1990.

[20] Glenn Krasner. Smalltalk-80: Bits of History, Words of Advice. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1983.

[21] Kai Li and Paul Hudak. Memory coherence in shared virtual memory systems. ACM Transactions on Computer Systems, 7(4):321~359, November 1989.

[22] Kai Li, Jeffrey Naughton, and James Plank. Concurrent real-time checkpoint for parallel programs. In Second ACM SIGPLAN Symposium on Principles and Practice of Parallel Programming. pages 79-88, Seattle, Washington, March 1990.

[23] Henry Lieberman and Carl Hewitt. A real-time garbage collector based on the lifetimes of objects. Communications of the ACM, 23(6):419-429, 1983.

[24] Raymond A. Lorie. Physical integrity in a large segmented database. ACM Trans. on Database Systems. 2(1):91~104, 1977.

[25] David A. Moon. Garbage collection in a large LISP system. In ACM Symposium on LISP and Functional Programming, pages 235-246, 1984.

[26] Mike O’Dell. Putting UNIX on very fast computers. In Proc. Summer 1990 USENIX Conf., pages 239-246, 1990.

[27] John Ousterhout. Why aren’t operating systems getting faster as fast as hardware? In Proc. Summer 1990 USENIX Conf., pages 247-256, 1990.

[28] Karin Petersen. personal communication, 1990.

[29] Paul Pierce. The NX/2 Operating System pages 51-57. Intel Corporation, 1988.

[30] Robert A. Shaw. Improving garbage collector performance in virtual memory. Technical Report CSL-TR87-323, Stanford University, 1987.

[31] Michael Stonebraker. Virtual memory transaction management. Operating Systems Review, 18(2):8—-16, April 1984.

[32] Patricia J. Teller. Translation-lookaside buffer consistency. IEEE Computer, 23(6):26-36, 1990.

[33] Charles Thacker, Lawrence Stewart, and Edwin Satterthwaite. Firefly: A multiprocessor workstation. IEEE Transactions on Computers, 37(8):909-920, August 1988.

[34] David Ungar. Generation scavenging: a non-disruptive high-performance storage reclamation algorithm. S/IGPLAN Notices (Proc. ACM SIGSOFT/SIGPLAN Software Eng. Symp. on Practical Software Development Environments), 19(5):157-167, 1984.

[35] David M. Ungar. The Design and Evaluation of a High-Performance Smalltalk System. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.. 1986.

[36] Paul R. Wilson. personal communication, 1989.

[37] Benjamin Zorn. Comparative Performance Evaluation of Garbage Collection Algorithms. Ph.D. thesis, University of California at Berkeley, November 1989.