In our previous discussions, we explored the power of EnTT, a high-performance C++ ECS library (especially its approach to relationship management), and separately, how to use Wasmtime for interactions between a C++ host and Rust-compiled WebAssembly (WASM) modules (a recap on WASM Interaction Basics). Today, we’re merging these two potent technologies to tackle a more challenging yet highly rewarding topic: How can we manage entity relationships using EnTT within a C++ host and expose this management capability safely and efficiently to a Rust WASM plugin?

This isn’t just a simple tech mashup. It strikes at the heart of several core challenges in modern software architecture: modularity, sandboxed security, high performance, and enabling effective communication between different tech stacks – particularly between traditional object-oriented languages like C++ and environments like WASM that don’t inherently understand objects.

Hitting the WASM Boundary with C++

Imagine a mature C++ application – perhaps a game engine, simulator, or desktop tool. We want to enhance its extensibility, security, or allow third-party contributions using a WASM plugin system. It sounds great in theory, but we quickly encounter a practical hurdle: the inherent boundary between the WASM module and the C++ host.

WASM operates within a strict sandbox. This imposes several crucial limitations when interacting with a C++ host. Firstly, WASM cannot directly access the host’s general memory address space; its view is confined to the explicitly exported linear memory buffer provided by the host. Secondly, direct calls to arbitrary C++ functions from WASM are forbidden; only functions explicitly exposed by the host through the WASM import mechanism can be invoked by the module. Thirdly, and often the biggest hurdle when coming from C++, WASM lacks any inherent understanding or capability to directly manipulate the host’s object-oriented concepts. It cannot work with C++ classes or objects in their native form, recognize inheritance hierarchies, or utilize virtual functions. As a result, attempting to instantiate a C++ object, directly call its member functions, or inherit from a C++ class from within the WASM environment is fundamentally impossible.

This poses a significant problem for developers accustomed to C++ OOP design. If we want a WASM plugin to interact with objects in the C++ application (like characters or items in a game world), simply passing C++ object pointers won’t work, and invoking member functions is impossible. Traditional plugin architectures, often relying on polymorphic interfaces via virtual functions, break down at the WASM boundary.

EnTT’s Data-Driven Philosophy

Just when this boundary seems insurmountable, EnTT’s design philosophy offers a way through. Recall the core tenets of

EnTT we discussed, which center on a data-oriented approach. An entity, in EnTT’s paradigm, is not an object in the

traditional C++ sense but rather a lightweight, opaque identifier (ID). This ID cleverly encodes an index and a version

number, providing a robust and safe way to reference a conceptual “thing” in the application without the complexities of

object identity or memory addresses. Data describing the state and properties of these entities is stored in

components. These are typically designed as pure data containers, often resembling Plain Old Data Structures (PODS),

and are directly associated with entity IDs within the system. The logic that operates on this data is encapsulated in

systems. Systems query for entities that possess specific combinations of components and then process them

accordingly. Within EnTT, systems are commonly implemented as straightforward free functions, lambdas, or functors that

interact with the central entt::registry to access and modify the component data associated with entities.

This data-driven approach is fundamentally different from OOP and aligns remarkably well with WASM’s interaction

model for several key reasons. First, the portability of EnTT’s entity IDs is paramount. Although entt::entity

incorporates internal complexity for safety (like versioning), it can be reliably converted into a simple integer type,

such as uint32_t, suitable for transmission across the FFI boundary. This integer ID then serves as a stable,

unambiguous handle for referencing a specific conceptual “thing” within the host’s EnTT world, eliminating the need for

the WASM plugin to comprehend complex C++ object memory layouts – it only needs the ID. Second, components naturally

function as data contracts between the host and plugin. Since components in EnTT are primarily data structures, their

defined memory layout can be agreed upon by both the C++ host and the Rust WASM plugin. By utilizing the shared linear

memory space exported by the host, both sides gain the ability to read and write this component data directly according

to the established structure, facilitating state synchronization. Finally, while direct invocation of C++ functions or

EnTT systems from WASM is prohibited, logic execution can be achieved indirectly. The host builds an interface by

providing a carefully selected set of C functions exposed via an FFI. These host-side FFI functions encapsulate the

necessary logic, interacting internally with the entt::registry to perform actions like creating entities, adding or

removing components, querying data, and, crucially for our case, managing relationships. The WASM plugin then simply

imports these specific FFI functions and calls them to trigger the desired operations within the host’s EnTT system.

This combination forms the cornerstone of our solution: We leverage EnTT’s portable entity IDs for cross-boundary referencing, utilize components as the shared data contract through linear memory, and construct an FFI API layer to serve as the essential bridge for invoking host-side logic from the WASM plugin.

Today’s Goal and Architecture Overview

This blog post will detail how we implement the EnTT relationship management patterns (1:1, 1:N, N:N) discussed previously, integrating them into the C++/Rust/WASM architecture.

On the C++ host side, the implementation involves several key components working together. An EnttManager class serves

as the central hub, encapsulating the entt::registry instance and implementing the specific logic for managing entity

relationships, thereby providing a clean, internal C++-facing API. To bridge the gap to WASM, a distinct C API layer,

defined in entt_api.h and implemented in entt_api.cpp, wraps the necessary EnttManager methods within extern "C"

functions. This layer ensures a stable FFI by using only C-compatible types and establishing clear conventions, such as

converting C++ bool to C int, defining a specific integer constant (FFI_NULL_ENTITY) to represent the null entity

state, and employing a two-call buffer pattern for safely exchanging variable-length data like strings and vectors

across the boundary. Finally, the WasmHost class, along with the application’s main function, orchestrates the

Wasmtime environment, setting up the Engine, Store, and optional WASI support. It utilizes the Wasmtime C++ API,

specifically linker.func_new with C++ lambdas, to register the C API functions as host functions importable by the

WASM module. A crucial step here is associating the single EnttManager instance with the Wasmtime Store’s user data

slot, enabling the host function lambdas to access the correct manager instance when called from WASM. The main

function concludes by initiating the interaction, typically by calling an exported function within the WASM module to

execute the defined tests or plugin logic.

Complementing the host setup, the Rust WASM plugin side is structured for safety and clarity. An FFI layer, residing in

ffi.rs, directly mirrors the host’s C API. It uses extern "C" blocks along with the

#[link(wasm_import_module = "env")] attribute to declare the host functions it expects to import. This module isolates

all necessary unsafe blocks required for calling the external C functions, providing safe Rust wrappers around them.

These wrappers handle the FFI-specific details, such as converting the C int back to Rust bool, mapping the

FFI_NULL_ENTITY constant to Rust’s Option<u32>, and correctly implementing the two-call buffer pattern to interact

with host functions that return strings or vectors. Above this FFI layer sits the core logic layer, typically within

lib.rs::core. This is where the main functionality of the plugin is implemented using entirely safe Rust code. It

operates solely through the safe wrapper functions exposed by the ffi.rs module, allowing it to interact with the

host’s EnTT world and manage entity relationships without directly dealing with unsafe FFI calls or raw memory

manipulation. For this demonstration, the core logic consists of tests exercising the various relationship management

functions provided by the host.

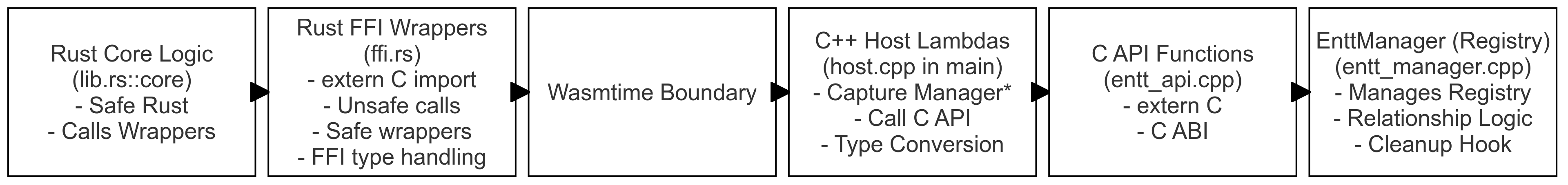

The architecture looks like this:

Let’s dive into the implementation details and design considerations for each part.

Crafting the C++ Host: The EnTT World and its WASM Interface

The C++ host holds the ground truth – the EnTT state – and defines the rules of engagement for the WASM plugin.

EnttManager: Encapsulating the EnTT World

Exposing entt::registry directly across an FFI boundary is impractical and breaks encapsulation. The EnttManager

class acts as a dedicated layer, managing the registry and offering a higher-level API focused on our specific needs (

entities, components, and relationships).

// entt_manager.h (Key Parts)

#include <entt/entt.hpp>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

// ... other necessary includes ...

class EnttManager {

private:

entt::registry registry_;

// Relationship Component definitions (PlayerRelation, ParentComponent, etc.)

// struct PlayerRelation { entt::entity profileEntity = entt::null; }; ...

// Internal helper methods for complex logic

// void unlinkPlayerProfileInternal(entt::entity entity); ...

// *** The Crucial Hook for EnTT's destroy signal ***

// Signature must match entt::registry::on_destroy

void cleanupRelationshipsHook(entt::registry& registry, entt::entity entity);

// The actual cleanup logic called by the hook

void cleanupRelationships(entt::entity entity);

// Static helpers for consistent ID conversion across the FFI

static uint32_t to_ffi(entt::entity e);

static entt::entity from_ffi(uint32_t id);

public:

EnttManager(); // Constructor connects the cleanup hook

~EnttManager();

// Prevent copying/moving to avoid issues with registry state and signal connections

EnttManager(const EnttManager&) = delete;

EnttManager& operator=(const EnttManager&) = delete;

// ... (move operations also deleted) ...

// Public API using uint32_t for entity IDs

uint32_t createEntity();

void destroyEntity(uint32_t entity_id);

bool isEntityValid(uint32_t entity_id); // Note: returns bool internally

// ... Component Management API (addName, getName, etc.) ...

// ... Relationship Management API (linkPlayerProfile, setParent, etc.) ...

};

Several key design decisions make the EnttManager effective. Strong encapsulation is maintained by keeping the

entt::registry instance private; all external interactions must occur through the manager’s public methods, offering a

well-defined and controlled interface to the underlying ECS state. To bridge the FFI gap for entity identification, the

manager handles ID conversion internally. While it uses the entt::entity type for its core operations, its public API

consistently exposes entities as simple uint32_t integers. Static helper methods, to_ffi and from_ffi, manage this

translation, ensuring correct mapping between the internal entt::null state and the designated C API constant

FFI_NULL_ENTITY. The implementation relies on the component-based relationship patterns previously established,

utilizing structures like PlayerRelation, ParentComponent, and CoursesAttended directly within the registry to

represent the connections between entities. Perhaps the most crucial feature is the automated relationship cleanup

mechanism. This is achieved by leveraging EnTT’s signal system within the EnttManager constructor, where a dedicated

hook method (cleanupRelationshipsHook) is connected to the registry’s on_destroy<entt::entity>() signal. This hook,

which matches the signal’s required signature (entt::registry&, entt::entity), simply forwards the destroyed entity to

the private cleanupRelationships(entt::entity) method. The essential behavior here stems from EnTT’s destruction

process: when registry.destroy() is called, the on_destroy signal is emitted first, triggering our cleanup logic

before the entity and its associated components are actually removed from the registry. This critical timing allows

the cleanupRelationships method to inspect the registry state while the soon-to-be-destroyed entity still technically

exists. Its responsibility is then to proactively find any remaining references to this destroyed entity held by

other entities (like a ParentComponent on a child or an entry in a CoursesAttended vector) and remove or nullify

those references, thereby automatically preserving relational integrity and preventing dangling pointers across the

system.

The C API Layer: A Stable FFI Bridge (entt_api.h/.cpp)

C++ features like classes, templates, and operator overloading cannot cross the FFI boundary. We need a stable interface based on the C ABI.

// entt_api.h (Key Parts)

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stddef.h>

#include <limits.h> // For UINT32_MAX

// Opaque pointer to hide C++ implementation

typedef struct EnttManagerOpaque EnttManagerHandle;

##ifdef __cplusplus

extern "C" {

##endif

// Define the null entity sentinel consistently for FFI

const uint32_t FFI_NULL_ENTITY = UINT32_MAX;

// Example Function Signatures

int entt_manager_is_entity_valid(EnttManagerHandle* manager, uint32_t entity_id); // Returns int (0/1) for bool

int entt_manager_link_player_profile(EnttManagerHandle* manager, uint32_t player_id, uint32_t profile_id); // Returns int

// Two-stage call pattern for getting variable-length data

size_t entt_manager_get_name(EnttManagerHandle* manager, uint32_t entity_id, char* buffer, size_t buffer_len);

size_t entt_manager_find_children(EnttManagerHandle* manager, uint32_t parent_id, uint32_t* buffer, size_t buffer_len);

// ... other C API declarations ...

##ifdef __cplusplus

} // extern "C"

##endif

// entt_api.cpp (Key Parts)

#include "entt_api.h"

#include "entt_manager.h"

#include <vector>

#include <string>

#include <cstring> // For memcpy

#include <algorithm> // For std::min

// Safely cast the opaque handle back to the C++ object

inline EnttManager* as_manager(EnttManagerHandle* handle) {

return reinterpret_cast<EnttManager*>(handle);

}

extern "C" {

// Example Implementations

int entt_manager_is_entity_valid(EnttManagerHandle* manager, uint32_t entity_id) {

return as_manager(manager)->isEntityValid(entity_id) ? 1 : 0; // Convert bool to int

}

int entt_manager_link_player_profile(EnttManagerHandle* manager, uint32_t player_id, uint32_t profile_id) {

return as_manager(manager)->linkPlayerProfile(player_id, profile_id) ? 1 : 0; // Convert bool to int

}

size_t entt_manager_get_name(EnttManagerHandle* manager, uint32_t entity_id, char* buffer, size_t buffer_len) {

std::optional<std::string> name_opt = as_manager(manager)->getName(entity_id);

if (!name_opt) return 0;

const std::string& name = *name_opt;

size_t required_len = name.length() + 1; // For null terminator

if (buffer != nullptr && buffer_len > 0) {

size_t copy_len = std::min(name.length(), buffer_len - 1);

memcpy(buffer, name.c_str(), copy_len);

buffer[copy_len] = '\0'; // Ensure null termination

}

return required_len; // Always return the needed length

}

size_t entt_manager_find_children(EnttManagerHandle* manager, uint32_t parent_id, uint32_t* buffer, size_t buffer_len) {

std::vector<uint32_t> children_ids = as_manager(manager)->findChildren(parent_id);

size_t count = children_ids.size();

// buffer_len is the capacity in number of uint32_t elements

if (buffer != nullptr && buffer_len >= count && count > 0) {

memcpy(buffer, children_ids.data(), count * sizeof(uint32_t));

}

return count; // Always return the actual count found

}

// ... other C API implementations ...

}

The C API layer adheres to several principles to ensure a stable and usable FFI bridge. It strictly follows the C

Application Binary Interface (ABI), using extern "C" linkage to prevent C++ name mangling and guarantee standard C

calling conventions, making it consumable from Rust and other languages. To hide the internal C++ implementation details

of the EnttManager, the API operates on an opaque handle, EnttManagerHandle*, which is essentially treated as a

void* pointer by callers. The interface itself is carefully restricted to use only fundamental C data types like

integers (e.g., uint32_t), pointers (char*, uint32_t*), and size types (size_t), avoiding any direct exposure of

C++ classes or complex structures. For boolean values, a common FFI convention is adopted where C++ bool is mapped to

a C int, returning 1 for true and 0 for false. Consistent representation of the null entity state across the boundary

is achieved using a predefined integer constant, FFI_NULL_ENTITY (defined as UINT32_MAX), which corresponds to the

internal entt::null value. Handling variable-length data, such as strings or vectors of entity IDs, requires a

specific strategy to manage memory safely across the WASM boundary. This layer employs the two-stage call pattern: the

caller first invokes the function with a null buffer pointer to query the required buffer size (e.g., string length

including the null terminator, or the number of elements in a vector). The caller (the WASM module in this case) then

allocates a buffer of sufficient size within its own linear memory. Finally, the caller invokes the C API function

again, this time providing the pointer to its allocated buffer and the buffer’s capacity. The C API function then copies

the requested data into the provided buffer. As a verification step and to handle potential buffer size mismatches, the

C API function returns the originally required size, allowing the caller to confirm if the provided buffer was adequate.

This pattern effectively avoids complex memory management issues and lifetime tracking across the FFI boundary.

WasmHost and Defining Host Functions via Lambdas

The WasmHost orchestrates Wasmtime. The critical part now is how it exposes the C API functions to the WASM module. We

settled on using the Wasmtime C++ API’s linker.func_new combined with C++ lambdas in main.

// host.cpp (main function, key parts)

#include "wasm_host.h"

#include "entt_api.h"

// ... other includes ...

using namespace wasmtime;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

// ... setup ...

WasmHost host(wasm_path);

EnttManager* manager_ptr = &host.getEnttManager(); // Pointer needed for capture

Linker& linker = host.getLinker();

Store& store = host.getStore();

host.setupWasi();

std::cout << "[Host Main] Defining host functions using lambdas..." << std::endl;

// Define Wasmtime function types

auto void_to_i32_type = FuncType({}, {ValType(ValKind::I32)});

// ... other FuncType definitions ...

// --- Example Lambda Definition (create_entity) ---

linker.func_new(

"env", "host_create_entity", // Module & Function name WASM expects

void_to_i32_type, // The Wasmtime function type

// The Lambda implementing the host function

[manager_ptr]( // Capture the EnttManager pointer

Caller caller, // Wasmtime provided caller context

Span<const Val> args, // Arguments from WASM

Span<Val> results // Where to put return values for WASM

) -> Result<std::monostate, Trap> // Required return signature

{

try {

// Call the stable C API function

uint32_t id = entt_manager_create_entity(

reinterpret_cast<EnttManagerHandle*>(manager_ptr)

);

// Convert result to wasmtime::Val and store in results span

results[0] = Val(static_cast<int32_t>(id));

// Indicate success

return std::monostate();

} catch (const std::exception& e) {

// Convert C++ exceptions to WASM traps

std::cerr << "Host function host_create_entity failed: " << e.what() << std::endl;

return Trap("Host function host_create_entity failed.");

}

}

).unwrap(); // unwrap for brevity, check Result in production

// --- Example Lambda Definition (add_name, needs memory access) ---

linker.func_new(

"env", "host_add_name", /* i32ptrlen_to_void_type */...,

[manager_ptr](Caller caller, Span<const Val> args, Span<Val> results) -> Result<std::monostate, Trap> {

// 1. Extract args: entity_id, name_ptr, name_len

// 2. Get memory: auto mem_opt = caller.get_export("memory"); ... check ... Memory mem = ...; Span<uint8_t> data = ...;

// 3. Bounds check ptr + len against data.size()

// 4. Read string: std::string name_str(data.data() + name_ptr, name_len);

// 5. Call C API: entt_manager_add_name(..., name_str.c_str());

return std::monostate();

}

).unwrap();

// ... Define lambdas for ALL functions in entt_api.h similarly ...

host.initialize(); // Compile WASM, instantiate with linked functions

host.callFunctionVoid("test_relationships"); // Run the tests in WASM

// ... rest of main ...

}

The integration within the WasmHost and the main function showcases several important techniques for exposing host

functionality to WASM. C++ lambdas serve as the essential bridge, adapting Wasmtime’s specific calling convention, which

involves receiving a wasmtime::Caller object and spans of wasmtime::Val for arguments and results (

Span<const Val>, Span<Val>), to the simpler, C-style signature of our C API functions which expect an

EnttManagerHandle* and basic C types. State is managed through lambda captures; by capturing the pointer to the

EnttManager instance (manager_ptr) obtained from the WasmHost, the lambda provides the necessary context to the

otherwise stateless C API functions, enabling them to operate on the correct EnttManager instance. It’s critical,

however, to be mindful of object lifetimes: the captured EnttManager pointer is only valid as long as the WasmHost

instance exists, meaning the host object must outlive any potential WASM execution that might invoke these

captured-pointer lambdas. For operations requiring interaction with WASM’s linear memory, such as passing strings or

buffers, the lambda must explicitly retrieve the exported Memory object using the provided wasmtime::Caller. Once

obtained, the lambda is responsible for accessing the memory data via the returned Span<uint8_t> and performing

rigorous bounds checking before reading or writing to prevent memory corruption. The lambdas also take responsibility

for data type marshalling, converting incoming wasmtime::Val arguments into the appropriate C types needed by the C

API functions, and converting any C API return values back into wasmtime::Val objects to be placed in the results span

for WASM. Finally, robust error handling is incorporated using try-catch blocks within each lambda. This ensures that

any standard C++ exceptions thrown during the execution of the C API or the lambda’s internal logic are caught and

gracefully converted into wasmtime::Trap objects, which are then returned to the WASM runtime, preventing host

exceptions from crashing the entire process.

Back to Rust: Consuming the Host API Safely

The Rust side focuses on interacting with the stable C API provided by the host, hiding the unsafe details.

The FFI Layer (ffi.rs): Managing the unsafe Boundary

This module is the gatekeeper between safe Rust and the potentially unsafe C world.

// src/ffi.rs

use std::ffi::{c_char, c_int, CStr, CString};

use std::ptr;

use std::slice;

// Constant for null entity

pub const FFI_NULL_ENTITY_ID: u32 = u32::MAX;

// Host function imports (extern "C" block)

##[link(wasm_import_module = "env")]

unsafe extern "C" {

// fn host_create_entity() -> u32; ... (all C API functions declared here)

fn host_is_entity_valid(entity_id: u32) -> c_int;

fn host_get_profile_for_player(player_id: u32) -> u32;

fn host_get_name(entity_id: u32, buffer_ptr: *mut c_char, buffer_len: usize) -> usize;

fn host_find_children(parent_id: u32, buffer_ptr: *mut u32, buffer_len: usize) -> usize;

// ...

}

// Safe wrappers

pub fn is_entity_valid(entity_id: u32) -> bool {

if entity_id == FFI_NULL_ENTITY_ID { return false; }

unsafe { host_is_entity_valid(entity_id) != 0 } // Convert c_int to bool

}

pub fn get_profile_for_player(player_id: u32) -> Option<u32> {

let profile_id = unsafe { host_get_profile_for_player(player_id) };

// Convert sentinel value to Option

if profile_id == FFI_NULL_ENTITY_ID { None } else { Some(profile_id) }

}

// Wrapper using two-stage call for strings

pub fn get_name(entity_id: u32) -> Option<String> {

unsafe {

let required_len = host_get_name(entity_id, ptr::null_mut(), 0); // Call 1: Get size

if required_len == 0 { return None; }

let mut buffer: Vec<u8> = vec![0; required_len]; // Allocate in Rust/WASM

let written_len = host_get_name(entity_id, buffer.as_mut_ptr() as *mut c_char, buffer.len()); // Call 2: Fill buffer

if written_len == required_len { // Verify host wrote expected amount

// Safely convert buffer to String (handles null terminator)

CStr::from_bytes_with_nul(&buffer[..written_len]).ok()? // Check for interior nulls

.to_str().ok()?.to_owned().into() // Convert CStr -> &str -> String -> Option<String>

} else { None } // Error case

}

}

// Wrapper using two-stage call for Vec<u32>

pub fn find_children(parent_id: u32) -> Vec<u32> {

unsafe {

let count = host_find_children(parent_id, ptr::null_mut(), 0); // Call 1

if count == 0 { return Vec::new(); }

let mut buffer: Vec<u32> = vec![0; count]; // Allocate

let written_count = host_find_children(parent_id, buffer.as_mut_ptr(), buffer.len()); // Call 2

if written_count == count { buffer } else { Vec::new() } // Verify and return

}

}

// ... other safe wrappers ...

The design of the Rust FFI layer (ffi.rs) prioritizes safety and ergonomics for the rest of the Rust codebase. A key

principle is the isolation of unsafe code; all direct calls to the imported extern "C" host functions are strictly

contained within unsafe {} blocks inside this specific module. This creates a clear boundary, allowing the core

application logic in other modules to remain entirely within safe Rust. The wrappers actively promote type safety by

translating between the C types used in the FFI signatures (like c_int) and idiomatic Rust types such as bool or,

for potentially null values, Option<u32>. For instance, the C API’s integer constant FFI_NULL_ENTITY is consistently

mapped to Rust’s None variant, providing a more expressive and safer way to handle potentially absent entity

references. Memory management for data exchanged via the buffer pattern (used for strings and vectors) is handled

entirely on the Rust/WASM side. The wrapper functions implement the two-stage call convention: they first call the host

API to determine the required buffer size, then allocate the necessary memory (e.g., a Vec<u8> for strings or

Vec<u32> for entity IDs) within WASM’s own linear memory space. This allocated buffer’s pointer and capacity are then

passed to the second host API call, which fills the buffer. The Rust wrapper subsequently processes the data safely, for

example, by using CStr::from_bytes_with_nul to correctly interpret potentially null-terminated strings received from

the host. This approach confines memory allocation and interpretation to the Rust side, avoiding cross-boundary memory

management complexities. Finally, basic error handling is integrated into the wrappers; C API conventions indicating

failure (like returning a size of 0 when data was expected) are translated into appropriate Rust return types, typically

Option or an empty Vec, signaling the absence of data or an unsuccessful operation to the calling Rust code.

The Core Logic (lib.rs::core): Safe Interaction

With the FFI details abstracted away, the core Rust logic becomes clean and safe.

// src/lib.rs::core

use crate::ffi::{ /* Import the necessary safe wrappers */ };

pub fn run_entt_relationship_tests() {

println!("[WASM Core] === Starting EnTT Relationship Tests ===");

// --- Test 1:1 ---

let player1 = create_entity(); // Calls safe ffi::create_entity()

let profile1 = create_entity();

add_name(player1, "Alice_WASM"); // Calls safe ffi::add_name()

assert!(link_player_profile(player1, profile1)); // Calls safe ffi::link_player_profile()

let found_profile_opt = get_profile_for_player(player1); // Calls safe wrapper

assert_eq!(found_profile_opt, Some(profile1));

// ... rest of the tests using safe wrappers ...

println!("[WASM Core] === EnTT Relationship Tests Completed ===");

}

The core logic operates purely in terms of Rust types and safe function calls, interacting with the host’s EnTT world indirectly but effectively.

Execution & Verification: Seeing it All Work

Running the C++ host executable produces interleaved output from both the host and the WASM module, confirming the interactions:

// [Host Setup] ... initialization ...

// [Host Main] Defining host functions using lambdas...

// [Host Setup] Initializing WasmHost...

// ... compilation, instantiation ...

[Host Setup] WasmHost initialization complete.

--- Test: Running WASM Relationship Tests --- <-- Host calls WASM export

[WASM Export] Running relationship tests...

[WASM Core] === Starting EnTT Relationship Tests ===

[WASM Core] --- Testing 1:1 Relationships ---

[EnttManager] Created entity: 0 <-- WASM calls host_create_entity -> C API -> Manager

[EnttManager] Created entity: 1

// ... other calls ...

[WASM Core] Unlinking Player 0

[EnttManager] Unlinking 1:1 for entity 0 <-- WASM calls host_unlink -> C API -> Manager

[WASM Core] Destroying Player 0 and Profile 1

[EnttManager] Destroying entity: 0 <-- WASM calls host_destroy -> C API -> Manager

[EnttManager::Cleanup] Cleaning ... FOR entity 0... <-- Host EnTT signal triggers cleanup *before* removal

[EnttManager::Cleanup] Finished cleaning for entity 0.

// ... more cleanup and tests ...

[WASM Export] Relationship tests finished.

[Host Main] WASM tests finished.

[EnttManager] Shutting down. <-- Host application ends

The logs clearly demonstrate the back-and-forth calls and, crucially, the execution of the EnttManager::Cleanup logic

triggered by registry_.destroy(), ensuring relationship integrity is maintained automatically.

Key Takeaways and Reflections

This journey integrating EnTT and WebAssembly underscores several crucial architectural principles. Foremost among them is the need to consciously embrace the boundary between the C++ host and the WASM module. Instead of attempting to force complex C++ concepts like object orientation across this divide, the successful approach involves designing a well-defined, stable interface using the C ABI. This FFI layer should rely on simple, fundamental data types and establish clear communication protocols, such as the two-stage buffer pattern employed here for handling variable-length data like strings and vectors.

EnTT’s inherent strengths proved particularly advantageous in overcoming the limitations faced by traditional OOP at the WASM boundary. Its data-driven philosophy, centered around portable entity identifiers (transmissible as simple integers) and data-only components, provides a natural and effective model for interaction. Entity IDs serve as reliable handles across the FFI, while component structures act as straightforward data contracts manageable within WASM’s linear memory.

The structural separation into distinct layers was also key to the project’s success and maintainability. Isolating the

core C++ EnTT logic within the EnttManager, providing a clean C API facade, creating safe Rust FFI wrappers in

ffi.rs, and implementing the main plugin logic in safe Rust within lib.rs::core results in a system that is easier

to understand, test, and modify safely. Furthermore, automating essential maintenance tasks, like relationship cleanup,

significantly enhances robustness. Leveraging EnTT’s signal system, specifically the on_destroy signal, allowed for

the automatic removal of dangling references when entities were destroyed, drastically reducing the potential for

runtime errors and simplifying the logic compared to manual tracking across the FFI.

Finally, this integration highlights the importance of using the provided libraries idiomatically. For Wasmtime’s C++

API (wasmtime.hh), this meant utilizing the intended mechanisms like linker.func_new with C++ lambdas for defining

host functions, rather than attempting to force the use of raw C function pointers with API overloads not designed for

them. Adhering to the intended usage patterns of the tools generally leads to cleaner, more correct, and often more

performant solutions.

Conclusion and Future Directions

We’ve successfully built a system where a Rust WASM plugin can interact with and manage complex entity relationships stored within an EnTT registry managed by a C++ host. This demonstrates that even sophisticated data structures and logic can be effectively bridged across the WASM boundary by leaning into data-oriented design principles and carefully crafting the FFI layer.

This opens up exciting possibilities: building extensible game engines where gameplay logic resides in safe WASM plugins, creating simulation platforms with user-provided WASM modules, or offloading specific computations to sandboxed WASM components within larger C++ applications.

While our example covers the fundamentals, there are several avenues for further exploration and refinement. Enhancing the robustness of error handling across the FFI, perhaps with more structured error codes or reporting mechanisms beyond simple boolean returns or traps, would be beneficial for production systems. Investigating alternative data serialization methods, such as Protocol Buffers or FlatBuffers, could offer more standardized or potentially more efficient ways to structure and transfer complex data structures through WASM’s linear memory compared to direct struct mapping. Furthermore, delving into advanced Wasmtime features like fuel metering for computation limiting or epoch-based interruption for cooperative multitasking could provide greater control over plugin resource consumption and responsiveness. Finally, staying informed about evolving WebAssembly standards, especially upcoming proposals like Interface Types, will be important, as these aim to substantially simplify the complexities of cross-language data exchange and function calls in the future.

The core takeaway remains: when object-oriented bridges struggle to cross the WASM chasm, EnTT’s data-driven philosophy paves a solid and efficient path forward. Happy coding in your bridged worlds!